Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance is not a textbook that explains why growth slowed in the 1970s. Nor is it a cookbook for how it can be restored. It is a tool in the intra-factional fight on the US left.

The goal is not to teach moderates how growth will be achieved but to demonstrate to the left that it should and can be achieved — that it is necessary for their political project and good on its own terms.

That makes it worthwhile for Europe. Even if the prescriptions and analysis in the book are wrong for the bloc, an explicit agenda framed around abundance is essential for the continent.

The book

The basic story of Abundance is that Democrats have neglected the supply side of the American economy. Even as demand increased, lack of supply has driven up prices of important outputs.

In 1950, the median home cost twice the annual income; 70 years later, it was six times the annual income. Construction productivity is now lower than it was 50 years ago, even as that in manufacturing has risen ninefold. Out of five key US energy transmission projects identified in 2016 to be completed in 2021, four have yet to start construction. After $23 billion and 15 years, California still has zero kilometers of working high-speed rail.

Some of the most important inputs in the economy — infrastructure, housing, energy — have actually become scarcer in the US over the last 50 years. According to Abundance, this scarcity is a choice.

Klein and Thompson believe the problems are due to the response to the New Deal and the Great Society — the great developmental programs between the 1930s and 60s. The programs were good, but they also gave America highways that tore up cities, rivers that caught fire, and smog-clogged towns.

In response, Democrats and Republicans alike decided to empower outside groups to prevent the government from doing things. In the 1960s and 1970s, over 25 different federal acts were passed as checks on new development.

CEQA, the California environmental rule that makes construction virtually impossible in the state, was signed into law by Ronald Reagan. The Environmental Protection Agency and Clean Air Acts were products of the Nixon administration.

In Abundance, many of these roadblocks were born out of good intentions. Costs have risen because Democrats want to do too many things: keep workers safe, clean up the environment, ensure biodiversity, have high-paying union jobs, provide affordable housing, and give neighbors a say.

Supposedly, the rules and groups that obstruct development are individually good but cumulatively have led to stasis.

In the world of Abundance, for the last half century America has been governed by two factions that are not interested in having the state succeed at the things that mattered; the right was busy trying to kill the government, and the left was trying to paralyze it with lawsuits.

Things could be radically better — the US could have clean energy, affordable houses, and much longer and healthier lives — if it had a politics that focussed on growth and a functional state encumbered by fewer rules. Klein and Thompson argue that forces that led to the slowdown were domestic and contingent — Johnson's Great Society, the New Deal, the thirty-year mortgage, and Ralph Nader. The left chose obstructionism as a way to correct against the excesses of modernity. To start winning elections again, they need to build a government that delivers abundance.

The Europe angle

Abundance frames 1970s obstructionism as an American phenomenon. But whatever happened to US happened on the continent as well.

Europe set out to be an environmental regulator at the 1972 Paris Summit, just two years after the creation of the American Environmental Protection Agency. Europe's flagship Environmental Action Programs date to 1973, just one year after the Clean Water Act. The Birds Directive — an evolution of which now plays a role in the Dutch nitrogen crisis — is from 1979.

When the book mentions Europe it does so positively. Its interventionist governments are attractive to Klein and Thompson. But across the metrics of housing, regulation, taxation, and energy there are obvious parallels between European economies and the Democrat-run US states Abundance criticizes.

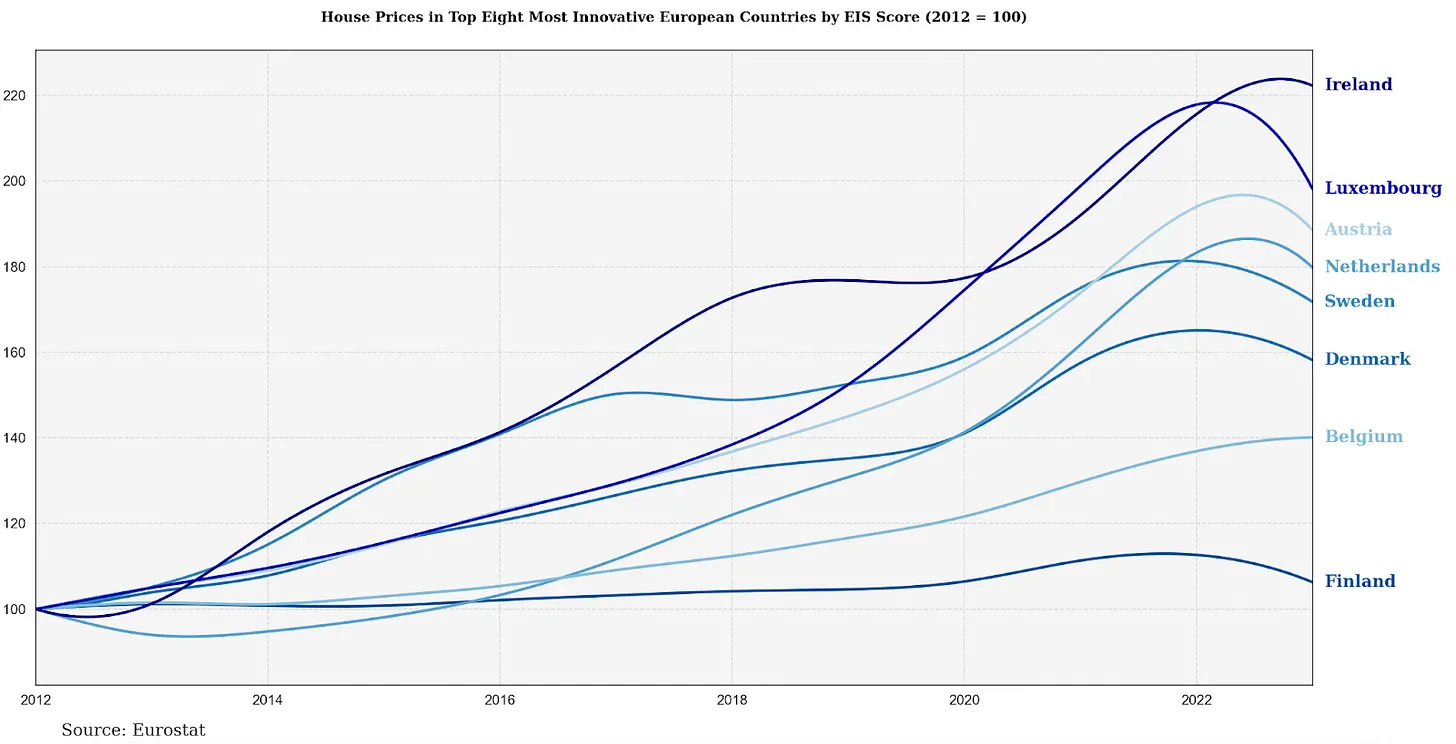

By 2022, 25% of Europeans aged 15 to 29 lived in overcrowded housing. Across Europe, newspapers are full of headlines about the ‘housing crisis’. Berlin’s apartment prices roughly doubled in the last ten years, while Dublin’s prices grew by 128%. This is not far from the US coastal experience; the Home Price Index for San Francisco increased by about 157% and by 51% in New York in the same period. .

Lengthy permit processes are a structural barrier in many European jurisdictions as well. A building project in Italy requires around 14 procedures on average to get a permit. In France, the mean permitting time was 220 days in 2023

The EU and US blue states both impose rigorous environmental reviews on new construction, transportation, and energy projects. Abundance worries about California’s CEQA, which requires detailed environmental impact reports (EIRs) for projects. The EU’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) directives and habitat protections are not much different. The new Berlin-Brandenburg Airport took 14 years to open, in part due to regulatory and planning holdups.

The EU as a whole had five times more wind power capacity stuck in permitting than under construction in 2022. Just one transmission project — Germany’s North Sea Ultranet — requires 13,500 permits. Over thirty percent of Europe’s significant cross-border electricity projects face permitting-related delays. Across the continent, transmission infrastructure is not coming online fast enough.

Household electricity prices in the EU averaged about $0.31 per kWh in 2024 roughly double the US average price of $0.16 per kWh. But California’s residential electricity averaged about $0.30 per kWh in 2024 – nearly double the U.S. average. New York’s electricity price is around $0.24/kWh. In Germany half of the bill was taxes and levies (including the renewable surcharge); in California, it is 25-30% of the bill.

In the book, Europe is a model to be copied. It shows how the government can improve outcomes for citizens, for instance by negotiating drug prices and building cheap infrastructure. It is a justification for why US unions cannot possibly play a role in the extraordinarily high costs of construction and weak state. After all, European countries build cheaper and ‘union density is higher in all those countries than it is in the United States’.

But Europe is less productive, growing more slowly, and lacks the innovation of the US. There are certainly areas where Europe does better than America. The cost of building a kilometer of rail in the US is almost twice as high as in Germany and more than six times as expensive as in Portugal. But the overall long-term growth slowdown is in America’s favor.

Interventionism has not delivered on the promise of abundance. Big, well-funded European states with plenty of civil servants, fewer veto points, and higher levels of public support suffer from the same problems as the blue states. California is still much more dynamic than any European country primarily due to the sector that its regulators have not touched: software.

European readers should pick up a copy not for its policy prescriptions but for its political objectives. Europe already does many of the things that a Klein Democrat would find attractive. The abundance agenda for Europe needs to revolve around a regulatory rollback, not a revival of state-driven innovation.1 Unlike in Abundance, this does mean many other priorities, whether environmental rules or data privacy, probably have to go.

The book is poor on energy and sometimes anti-market. It frames global stagnation as an American phenomenon. The authors are against what they call everything-bagel liberalism — trying to do everything at once — but do not find many Democratic interest groups that must sacrifice their interests.2 It retains affection for many of the interventionist policies of the post-liberal left.

If that is the price of making a leftwing case for material prosperity, it is worthwhile. We need S&D MEPs to read Abundance and decide that growth is the most important objective in politics.

Klein and Thompson argue low public investment in science is causing American innovation to slow. As a share of GDP, Europe spends more (0.74%) on public sector R&D than the United States (0.69%)

It is surprising how much the California and Biden administration officials they interview — many of whom were deeply implicated in the largest failures described in the book — sound like Klein and Thompson. They complain about the same things: ‘rules’, ‘procedure’s, ‘America’s failure to build’. Talking about abstract interest groups seems easier than identifying which parts of your coalition to eject is much harder.

To claim that the Birds Directive is at the root of the nitrogen crisis is quite a stretch. If anything, it is the Habitats Directive from 1992 (as you correctly refer to in your original piece on this subject) because it contains the legal base for the "verslechteringsverbod" (art. 6.2) which is the main point of contention in the various legal cases we saw in the Netherlands. But even then, that is a gross simplification that neglects a whole range of other factors.