Failure Costs

An Answer to the FT’s Trillion Dollar Question

Last week the Financial Times published a piece by British entrepreneur Ian Hogarth with a provocative question: can the EU build a trillion dollar company? Hogarth responds that the EU first needs to solve a lack of experienced founders, a lack of ‘audacious capital’, and excessive US buyouts.

These answers, according to a recent paper by Olivier Coste and Yann Coatanlem, two French entrepreneurs, miss the point: the reason more capital doesn’t flow towards high-leverage ideas in Europe is because the price of failure is too high.

Coste estimates that, for a large enterprise, doing a significant restructuring in the US costs a company equivalent to two to four months of pay per worker. In France, that cost averages around 24 months of pay. In Germany, 30 months. In total, Coste and Coatanlem estimate restructuring costs are approximately ten times greater in Western Europe than in the United States.1

Bloomberg (April 2023)

These costs kick in when a major venture has failed; it follows that the higher the probability of failure in a sector, the greater the relative disadvantage for Europe. The lack of repeat founders and ‘audacious’ venture capital are symptoms of this underlying malady.

Consider a simple example. Two large companies are considering whether to pursue a high risk innovation. The probability of success is estimated at one in five. Upon success they obtain profits of $100 million, and the investment costs $15 million.2

One of the companies is in California, where if the innovation fails the restructuring costs $1 million. The other company is in Germany, where restructuring is 10x more expensive, it costs $10 million (a conservative estimate).3

The expected value of this investment in California is a profit of $4.2 million. In Germany the expected value is a loss of $3 million.

This dynamic pushes European companies toward sticking with what they already know — not because they're more risk-averse, but because it’s the profit-maximising choice given the cost if they fail. Making big bets on new technologies is less worthwhile for big European firms. The widening innovation gap reflects the repeated effect of the structural advantage from cheaper restructuring, increased by (arguably) faster technological change.

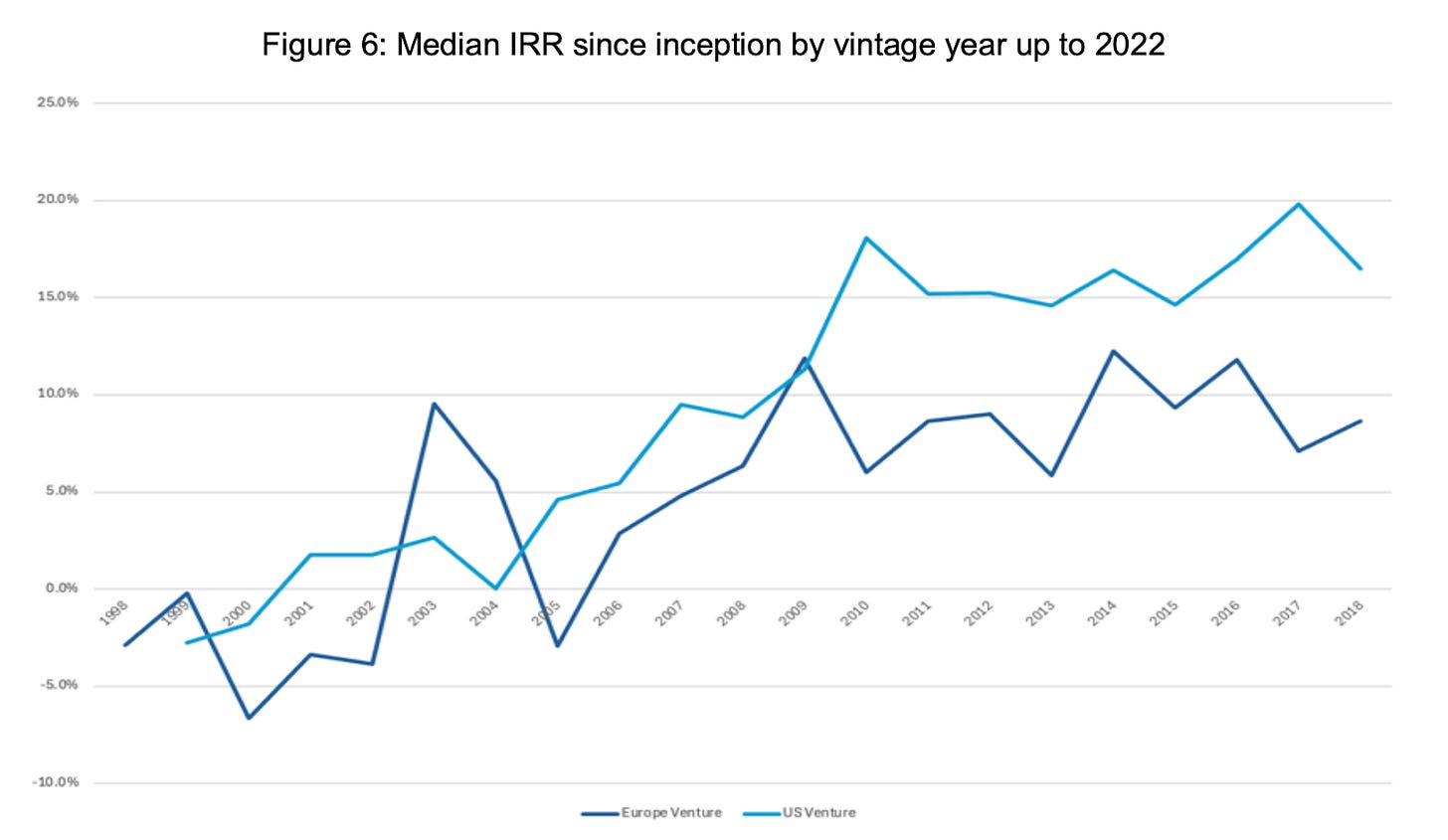

Coste and Coatanlem’s calculation implies that the higher European restructuring costs should lead to an internal rate of return four points lower than in countries with more flexible Employment Protection Legislation (EPL).4 Comparing averages from two VC return indices shows that the difference in internal rate of return (IRR) between the EU and the US between 1998 and 2018 is close to that — five points.5

Under this theory, rather than a cultural problem or a lack of experience, European VCs are minimizing exposure as a rational response to the (lower) expected value of investments in disruptive innovation.

The failure costs thesis fits other facts. As Saint-Paul (2002) identifies, Europe does well in ‘secondary innovation' — incremental improvement of existing products, such as what takes place at companies like Michelin — but struggles with 'primary innovation' (inventing new products), where the failure rate is higher, and thus the expect restructuring penalty is higher.6

Among large companies, between 2014 and 2019 average returns on invested capital were 20% lower in the EU than the US, with 90% of these differences being due to ICT and pharmaceuticals.7 US venture capital funds do come to Europe — but they are concentrated in the UK, the country that happens to have the most flexible employment law in Europe after Switzerland and Hungary.8

Bartelsman, Gautier and De Wind (2016) find that countries with high firing costs have smaller and more unproductive high-risk sectors. They are unequivocal:

“The extent to which a country can benefit from the advantages of risky technologies depends on the institutional arrangements on firing and bankruptcy. The more employment protection there is, the more costly it is to exercise the job destruction or firm exit option, which becomes more important when new risky technologies become available.”9

When European technology companies try to pivot, the costs are visibly significant: in France, Atos failed to adapt to cloud services and is close to bankruptcy after spending 10% of revenue on restructuring in 2022.10 Volkswagen is being severely disrupted by weak demand and foreign competition in EVs, but their 2023 restructuring remains in limbo because the company's work council so far has refused to accept any factory closures.11

We have seen a strong bifurcation in AI adoption. US firms have been decisive:

“Microsoft streamlined its workforce, invested $10 billion in OpenAI, and more in its own AI infrastructure.”

“Meta paused its metaverse efforts, laid off 20,000 employees within months, and boosted its AI investments, spending a whopping $37 billion on computing infrastructure in 2024.”

“Google, facing challenges in search, halted major projects, laid off 12,000 employees, and accelerated on AI by ramping up its R&D investments to $43 billion in 2023”12

In comparison, Europe’s software leader, SAP has been slow. Its AI investment sits at just $0.6 billion per year — two orders of magnitude lower.13 While it has announced 8,000 lay-offs, “it is provisioning over 18 months of compensation globally, with more than three years required in Europe.”14

All this implies that failure costs are indeed a problem for top European firms. Why isn’t this a bigger issue?

The first reason is a lack of precise data. The index commonly used to track EPL costs is the OECD’s Indicators of Employment Protection. While good, it is primarily built using “the Secretariat’s own reading of statutory laws, collective bargaining agreements and case law.”15

It is a qualitative assessment. It doesn’t involve collecting data from companies to understand how rules and norms work in practice. According to Coste, that data doesn't exist because companies are reluctant to share it, as it would reveal bargaining practices. When it comes to understanding the scale of the issue, we are functionally flying blind.

The second problem is a lack of appealing solutions. Employment protection law is (understandably) a very sensitive subject. It is not an EU competence, and reforms are always extremely controversial. Draghi, who has been willing to call out many of Europe's mistakes on innovation, only has the following to say:

“EU companies face higher restructuring costs compared to their US peers, which places them in a position of huge disadvantage in highly innovative sectors characterised by the winner-takes-most dynamics”16

It is a source of 'huge disadvantage' but receives no other mention in the 300+ pages of the report!

There could be solutions to this issue that aren’t problematic for the social model. Coste and Coatanlem suggest having flexible employee protection only kick in at a certain income percentile, say the top 5-10%. (The downside of this is that you create a huge marginal tax whenever that threshold is set, distorting employees away from the most effective firms.) Denmark operates the famous ‘flexicurity’ model:

1. Employers can hire and fire at will.

2. Employees pay subscription fees to a government unemployment insurance fund and get up to two years' benefits after losing their jobs.

3. The Danish government runs education and retraining programs.

It means both that workers have protections and companies can be agile. While no Silicon Valley, by the European Commission’s metrics Denmark is the EU’s top innovator.17

There are certainly other channels that affect innovation competitiveness. But the cost of failure is critical to risk-taking. Cette & Lopez (2018) found that switching to US style EPL would increase R&D intensity in France by 54%, Germany by 33%, Netherlands by 32%, and Italy by 41%.18

Every ‘trillion dollar start-up’ has reinvented itself. Google didn't rely on PageRank alone — it went on to build YouTube, AdSense and Android. Microsoft now makes more money through Azure and its cloud services than Windows. NVIDIA started making gaming hardware and is now the world’s largest AI company.

Many of these attempts were not successes. Apple’s driverless car ambitions, Google's various social-media forays and Meta’s VR products are all failures. Over the long term, whether a company grows is a function of whether it continues to adapt. If it wants its trillion dollar company, Europe probably needs to let its biggest firms take bold bets that fail.

References:

Bartelsman, Eric J., Gautier, Pieter A., and De Wind, Joris. "Employment Protection, Technology Choice, and Worker Allocation." International Economic Review 57, no. 3 (August 2016): 787-825.

Coatanlem, Yann, and Coste, Oliver. "Cost of Failure and Competitiveness in Disruptive Innovation." IEP@BU Policy Brief, September 2024.

Cette, Gilbert, Jimmy Lopez, and Jacques Mairesse, "Employment Protection Legislation Impacts on Capital and Skills Composition," Economie et Statistique, no. 503-504, 2018.

European Commission. "European innovation scoreboard." Research and Innovation - European Commission, 2024.

McKinsey Global Institute. "Securing Europe's competitiveness: Addressing its technology gap." McKinsey & Company, 2022.

OECD. "OECD Indicators of Employment Protection." OECD.org, 2024.

Reuters. "VW plans for factory closures cross several red lines, works council chief says.” Reuters.com, November 2024.

Saint-Paul, Gilles. "Employment protection, international specialization, and innovation." European Economic Review 46, no. 2 (February 2002): 375-395.

Coatanlem, Yann, and Oliver Coste. "Cost of Failure and Competitiveness in Disruptive Innovation." IEP@BU Policy Brief, September 2024.

In reality, the calculation is still more skewed: the profit is shrouded in greater uncertainty than the potential loss

Coste and Coatanlem (2024)

Coste and Coatanlem (2024)

Coste and Coatanlem (2024)

Saint-Paul, Gilles. "Employment protection, international specialization, and innovation." European Economic Review 46, no. 2 (February 2002): 375-395.

McKinsey Global Institute. "Securing Europe's competitiveness: Addressing its technology gap." McKinsey & Company, 2022.

Bartelsman, Eric J., Pieter A. Gautier, and Joris De Wind. "Employment Protection, Technology Choice, and Worker Allocation." International Economic Review 57, no. 3 (August 2016): 787-825.

Personal estimates from Oliver Coste

Reuters. "VW plans for factory closures cross several red lines, works council chief says.” Reuters.com, November 2024.

Coste and Coatanlem (2024)

Coste and Coatanlem (2024)

Draghi, Mario. 2024b. "EU Competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations" EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

European Commission. "European innovation scoreboard." Research and Innovation - European Commission, 2024.

Cette, Gilbert, Jimmy Lopez, and Jacques Mairesse, "Employment Protection Legislation Impacts on Capital and Skills Composition," Economie et Statistique, no. 503-504, 2018.

Great post and publication, thank you, Pieter.

Definitely an overlooked matter with multiple ramifications. The ability to size up and down is critical to enable fast iteration and adaptation of young ventures. The consequences on talent attraction are also dramatic. Leaving a well paid job after a >10-year tenure, foregoing severance/exit bribe, to found or join an innovative company is outright irrational for many in most of continental Europe. Talent is just rotting away, waiting to cash out an oftentimes life-changing sum.

However, as a VC myself, I don't think obstacles to restructuring are directly weighing down in the risk appetite of European VCs, as implied in the article. At least they are not too high in the list. It is well researched that VC returns are disproportionally driven by large wins rather than by minimising losses, which will be capped by the corporate veil in a failed venture, as opposed to a large corporation trying to innovate.

Congrats, fantastic post!