Europe’s economic debate has taken a curious turn. Many now insist that to escape stagnation, the EU should abandon “neoliberal” austerity and borrow more. They see fiscal rules as roadblocks to progress, so they call for debt‐fueled industrial policy. Mario Draghi’s recent Paris CEPR lecture captures this view: while he acknowledges how red tape hurts EU innovation, he emphasizes increased EU borrowing over urgent regulatory reform.1

But Europe's struggles do not stem from insufficient public spending. In fact, over the last decade, we have experienced an unprecedented debt explosion. For instance, national measures to shield consumers and firms from the energy crisis cost €651bn euros in 16 months to January 2023, according to Bruegel. That is the bill for just one of our several recent one-in-a-century crises.

The problem is that, during its supposed "neoliberal" period, Europe has in fact steadily increased constraints on businesses and individuals — from product liability mandates to environmental and digital rules — while avoiding genuine market liberalization in services, including professional and financial services. Instead of taking low growth as evidence that more deficit spending is needed, Europe should see it as evidence that we need to bite the bullet and undertake real microeconomic reforms.

Europe has success stories

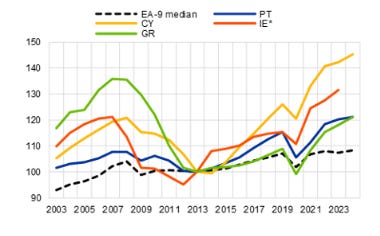

Evidence of what is possible comes from countries forced to implement genuine structural reforms during the euro crisis. Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Cyprus provide a natural experiment in the power of following the traditional consensus (fiscal restraint and structural reform) to deliver growth. According to ECB analysis, all four countries have outperformed the rest of the eurozone in growth and job creation over the past decade.

Figure 1: Real output per capita in Reform and Core Countries. 2013=100; EA: Initial Euro Members minus GR and Ireland. Source: Filip et al. (2024).

They have seen stronger employment growth and faster real output per capita increases than the core eurozone nations. Some view this as an inevitable bounce back after huge recessions. But this does not explain why they've proven more resilient to shocks. Despite the pandemic, Ukraine war, and energy crisis, they've maintained their stability and outperformance.

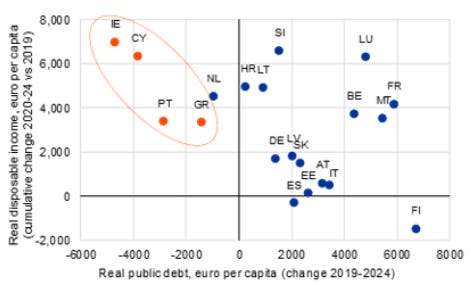

What drove this success? Not more debt — as the figure below shows. What worked was the much-derided ‘neoliberal’ consensus: Restraint, restructuring labor markets, freeing up goods markets, and reducing business regulations to boost flexibility and sound public finances. Portugal liberalized regulated professions and reformed its judicial system to speed up commercial cases. Greece improved its business environment through reforms like simplifying licensing. Meanwhile, high‐spending states like France have seen lower growth despite large deficits, with the result that France is currently paying a higher interest rate to fund its debt than Greece.

Figure 2: Change in debt and disposable income in Reform and Core Countries. Source: Filip et al. (2024).

Debt isn’t a free lunch

There are institutional reasons to worry about debt. Not long ago, many (including me!) hoped that large debt-funded EU programs could increase reforms and long-term growth in slow-growing countries. The reality is that there has been little reform. The European Commission, intended to be a neutral referee, consistently gave top marks to most national plans, suggesting political considerations trumped strict evaluation.

Take the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Created after COVID-19, it was supposed to tie investments to structural reforms. Italy was the largest beneficiary. Instead of leading to reform, it has given rise to much more waste.

The recent Super Bonus scheme offers an example. The Italian program covered 110% (!) of home energy-efficiency renovations. Neither homeowners nor contractors had any incentive to control costs. Originally budgeted at €35 billion, the total ballooned to an estimated €225 billion — over 10% of Italy’s GDP, nearly triple the entire sum of grants Italy stands to receive from the RRF.2 Two large public investment projects in Germany during the last two decades – the Berlin airport and the Stuttgart 21 railway project - similarly illustrate wasteful public investment implementation.

This is the primary flaw in the “borrow your way to growth” model: without proper incentives and oversight, borrowed money tends to flow toward politically expedient spending rather than productive investment. Member states face strong incentives to use funds for visible, short-term benefits rather than structural reforms.

Condemning Italy's misuse of EU transfers could be merely a criticism of poor public spending, not a valid argument against greater use of debt. However, this overlooks the fact that the effectiveness of debt depends on how it is utilized. Borrowing to fund public expenditures without robust institutions leads to waste and erodes public trust. The problem with industrial policy isn’t that money can’t be spent well, but that it likely won’t be. Italy’s example illustrates that the absence of mechanisms to guarantee responsible spending transforms debt into a tool for mismanagement rather than growth.

There are more reasons to worry about a large increase in public spending in Europe. Over the past decade, some economists have claimed we shouldn't worry about government debt: if the interest rate (r) on public debt remains below the economy’s growth rate (g), primary deficits could persist while the debt-to-GDP ratio shrinks.

However, this “free lunch” argument only works if Europe can attain robust growth. Without reforms, demographics and productivity trends say otherwise:

By 2050, roughly one in three Europeans will be over 65. With birth rates well below the 2.1 replacement rate (around 1.5 on average, and below 1.2 in countries like Italy or Spain), Europe’s working-age population is declining rapidly while the retired population grows. Immigration could help but currently does not tilt toward high-skilled workers who would boost fiscal sustainability.

Labour productivity growth in Europe since 2015 has been stuck at 0.7%. (This poor performance accounts for more than half of the gap in per capita GDP growth with the US.3) Real taxable income in the eurozone has grown at a meager 1.3% annually over the past decade. In high-debt countries like Italy and France—where government spending already exceeds half of GDP — growth drags are especially severe.

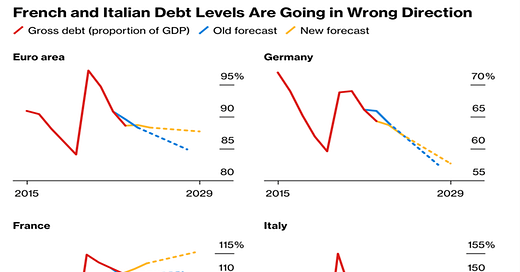

Figure 3. Euro area, Italy Germany, France Debt Projections. IMF WEO April 2024.

Once we factor in implicit pension liabilities—already approaching 400% of GDP for France and Italy—true debt burdens soar beyond official figures.

Figure 4. Accrued-to-date pension entitlements in social insurance Eurostat, last available (2021).

It is true that we cannot precisely identify the safe debt limit for large economies that issue their own currency. But this argues for caution rather than comfort. Market sentiment can shift rapidly, as Britain's 2022 experience shows. More importantly, high debt levels reduce policy flexibility when crises hit. The right path is to strengthen our economies' fundamentals while debt costs remain manageable, rather than testing the limits of market tolerance.

To alleviate national burdens, proponents want more borrowing at the European level. This can help in some narrow, critical cases like defense. But the EU is not a federal system with substantial revenue streams based on our own taxes. It has a patchwork of "own resources" (customs duties, VAT-based contributions, and a plastic levy) that cover only a fraction of the budget; the bulk—around 70%—still comes from direct contributions from member states based on their Gross National Income (GNI), which are renegotiated every 7 years.

Every euro of EU debt ultimately becomes a future claim on member states. The NextGen EU program will require around €30 billion per year for debt service from 2028 onward — money that will come from national contributions if no new EU taxes can be agreed. This fuels constant political tension over "net contributions," with net contributors like Germany and the Netherlands resisting measures that effectively shift more obligations their way. Though EU debt benefits from strong legal guarantees, investors know the EU is only as good as member states' political willingness to foot the bill in the future. Without a genuine federal tax system, this willingness remains uncertain — as a result risk premiums may exceed medium-quality national bonds (Bonfanti and Garicano, 2022).

Figure 5. Five year sovereign yields to maturity. Source: Giovanni Bonfanti (2024).

The road ahead

Rather than abandon the Macro consensus, Europe needs to be serious about pro-market reforms and completing the Single Market for services. Countries that implemented structural reforms are thriving, while those pursuing debt-fueled growth struggle. Structural reforms, not debt issuance, remain the real solution. The Draghi report’s best advice highlights the harm of overlapping rules, excessive regulations that hinder innovation and an almost complete lack of market integration in the service sector. In particular, the Capital Markets Union seems long overdue and uncontroversial with voters—only opposed by small powerful interests. Europe needs simpler regulations, permitting reforms, mutual recognition of standards, and fewer environmental and digital rules.

There is a place for public investment in genuine public goods, like infrastructure, defense, cross-country electricity interconnections, and basic research. Defense requires a fast ramp-up, and issuing (European) debt here is entirely justified. But for long-term private sector growth — bringing back innovation — the solution won’t be another mega-fund. Without addressing the regulatory barriers that hold back growth, debt-fueled industrial policy will only delay necessary changes and make us more vulnerable to future crises. Europe's future depends not on more dirigisme funded by new borrowing, but on firms being free to grow.

Thanks to Klaus Masuch and Andrés Velasco for comments on an earlier version.

References

Boeri, Tito and Roberto PEROTTI, “PNRR. La grande abbuffata”, Milano, Feltrinelli, 2023, pp. 208.

Bonfanti, Giovanni, Convenience Yields in Euros: Investment Mandates and Conditional QE (January 19, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4700662

Bonfanti, Giovanni and Luis Garicano. “Do financial markets consider European common debt a safe asset?” Bruegel, 08 December 2022.

Cochrane, John, Luis Garicano and Klaus Masuch. “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro”, Forthcoming (Spring 2025) Princeton University Press.

Filip, Daniela, Klaus Masuch, Ralph Setzer and Vilém Valenta, “Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus: Crisis and Recovery,” The ECB Blog, 3 December 2024

Giavazzi, Francesco, and Chiara Goretti. "Is Italy's RRF plan working, or is it just another waste of money?." CEPR Policy Insight 130 (2024).

His recent CEPR Paris speech reflects this focus on demand management: “From 2009 to 2019, the collective cyclically-adjusted fiscal stance in the euro area averaged 0.3%, compared with -3.9% in the US. And if we look at primary deficits in absolute terms, measured in the 2023 euros, the US government injected 14 times more funds into the economy, 7.8 trillion euros in the US and 560 billion in the euro area…. The euro area experiences longer periods where the economy is operating below potential — and this inability to maintain demand pressure then feeds back into productivity growth.” ECB board member Fabio Panetta called for €800bn annual borrowing, calling it “small at central level”. In a November 1st FT OpEd, Draghi writes “analysis by the ECB suggests that there is scope for public investment to expand significantly if governments take full advantage of the EU’s new fiscal rules. The ECB estimates that the new rules — which allow countries to extend fiscal consolidation for up to seven years in order to carry out investments and reforms — could in principle unlock up to €700bn. And once the consolidation phase is over, countries are allowed to keep structural deficits at 1.5 per cent of GDP. “

See the evaluation of Italy’s non-reforms by Boeri and Perotti (2023). For a much more positive view, partialy from inside the Italian government, see Gavazzi and Goretti (2024).

“Around 70% of the gap in per capita GDP with the US at PPP is explained by lower productivity in the EU” (Draghi, 2024).

Having been involved in some of the policy-making episodes quoted in the piece I can only agree on each and every point it makes.

Let me add that would not have been any chance that the hugely wasteful Superbonus scheme in Italy be implemented if the EU fiscal rules had not been suspended because of Covid. Even ‘stupid’ rules such as the 3 percent deficit limit are needed to prevent even more stupid policies.

The Draghi report does contain a strongly critical message on EU regulation, especially in the digital domain, and on the need to overcome market fragmentation including through radical means such as the 28th regime for innovative companies. It also has broadly the right message on competition policy as a spur not impediment to EU growth (apart from a misguided analysis on telecom consolidation). For some strange reason however Draghi himself is emphasising the macro recommendations on more borrowing, which have already attracted most of the public attention. This plays in the hands of those blaming all the economic ills affecting Europe on ‘austerity’.

Interesting article. Just a point to think about coming from Greece. Resilience also comes from the people and not only the economic/fiscal policies. Greeks have been leaving in extremely turbulent time for around 10 years of economic crisis. This has taken a toll on everybody but has taught the people to take nothing for granted and build resilience and become more susceptible to change