‘Fat, dumb, and happy’ — ASML CEO Peter Wennink on the Netherlands

‘The inhabitants were here before ASML, and they will be here after ASML… when all the high-tech machines have been recycled…as Philips was before them’ — Veldhoven city councilor from Party of the Elderly explaining his opposition to further ASML expansion.

The recent Draghi (2024) report on EU competitiveness mentions housing just twice.1 Solutions to housing scarcity, when they are proposed, often revolve around subsidizing demand or imposing rent controls, creating more scarcity. The continent needs an alternative approach. The evidence from Europe and from the literature is clear: to do better at technology the continent needs to build many more homes.

Housing affects innovation

We know cities with a less elastic housing supply see economic growth absorbed in higher rents and lower welfare for workers. But housing scarcity also reduces innovation. This tends to happen through two main channels:

First, high housing costs destroy agglomeration effects. Shortages increase transportation costs for people and ideas. Innovation involves combining ideas, so there are strong benefits from being in close proximity to other smart people with good ideas.2

A single successful start-up requires the presence of multiple extraordinary founders, top initial talent, and sufficient venture capital. For all three, there is imperfect substitution (you cannot use many bad founders in the place of a few outstanding ones) — and the performance of start-ups tend to follow power laws (so the different factors are multiplicative). All effects increase the returns of co-location. The idea of agglomeration effects explains the dominance of innovation superclusters (e.g. like the Bay Area) in the history of technology.

Second, high housing costs generally prevent people from moving towards areas and industries where they would be more productive. Hsieh and Moretti (2019) estimate that if just the Bay Area and New York would reduce restrictions to the U.S. average, total U.S. GDP would be 9% higher.3 In Europe, De la Roca and Puga (2017) find that a worker moving from the median-sized Spanish city to Madrid would see an immediate 9% wage gain, growing to a 36% premium after 10 years.4 Shortages in the housing stock serve as breaks on growth across the board, with downstream effects on the technology sector.

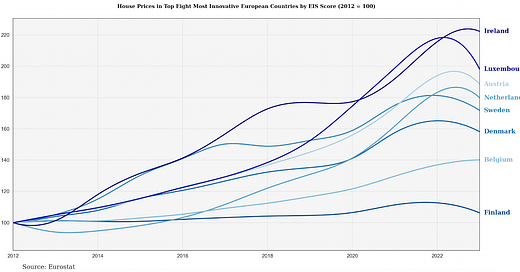

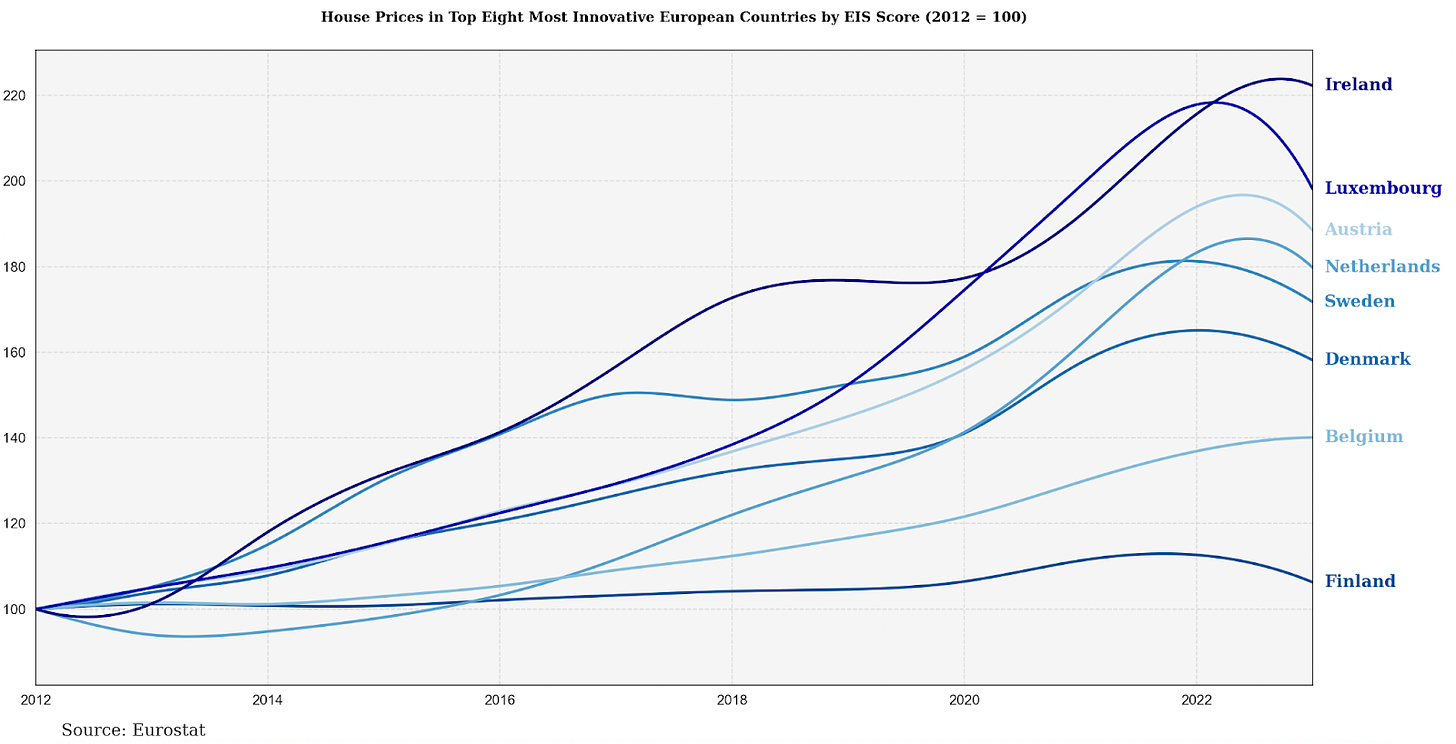

House prices are rising rapidly across most of Europe. They are outpacing inflation in every one of the eight most innovative countries but one. The exception, Finland, had a recent construction boom. In Estonia, an Eastern Europe innovation leader, rents have more than tripled since 2010. The population there has grown by more than 15% in the 10 years leading to 2021, largely driven by foreign tech workers settling in Tallinn.5 In some instances, the effects of high housing costs are directly undermining the ability of European firms to compete on the global stage. For evidence of this, we can look to the Netherlands and ASML.

The case of ASML

The Draghi report states that “no EU company with a market capitalisation over €100 bn has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years, while all six US companies with a valuation above €1 tn have been created in this period." The key words here are “from scratch” — semiconductor equipment manufacturer and Europe’s largest tech firm ASML was spun off from Philips in 1984.

As a firm, it is probably the greatest European tech success story: the third largest company in the EU by market cap (after pharma giant NovoNordisk, and luxury conglomerate LVMH ) and the EU’s only significant contribution to the microelectronics and AI supply chains. It is so influential that it has elevated the Netherlands to one of the White House’s critical partners in its rivalry with China.

But to continue to grow it needs to be able to build. In particular, ASML relies on foreign talent for a large share of its workforce. Over 60% of ASML’s employees are foreign nationals. An ASML engineer I met recently (he was on a lengthy vacation while installing EUV machines) mentioned that in a few years he had gone from leading a fully Dutch team to being one of the last Dutch members.

In the last few years, it has been struggling to house that headcount. In 2021, the region where ASML is based, Brainport Eindhoven saw rents rise faster than anywhere else in the country. Thanks to the firm's growth, Eindhoven's plan to add 20,000 homes by 2030 needs to be doubled. Hitting that target requires building 5,500 homes annually. Last year's actual addition was just 1,380 homes.

The problems eventually got so bad that ASML threatened to scale down its Dutch operations.6 During a recent presentation of annual figures, ASML CEO Peter Wennink said that if the firm could not find and bring qualified workers to the Netherlands, the firm would seriously consider directing future growth abroad.7 ASML CFO Roger Dassen explained why: “Far too few homes are built in the Netherlands. That is the real problem.” 8

This scarcity is a country-wide issue. The housing stock has not expanded at the same pace as the population, with shortages resulting. For the past decade, the Netherlands should have added roughly 100.000 new houses each year to keep up. It has been building just two thirds of that.

This is mostly due to regulatory constraints on growth. A judicial ruling on nitrogen emissions led the state to freeze new construction entirely in 2019, and continues to hamper new construction. Only 13% of total land is allocated for commercial or residential use. Most cities have severe height limits and residential skyscrapers are virtually non-existent.

There are deeper structural problems. Dutch planning is slow and gives a lot of say to NIMBYs. A large group of neighbors attempted to block ASML’s latest factory expansion with complaints about noise and visual pollution. Rather than fixing this problem, the Dutch government could be aggravating it: a major reform to zoning law adopted in January streamlined procedures, but made civic participation in zoning a legal obligation.

Faced with a crisis, the political system has decided to make matters worse. Out of a desire to protect vulnerable constituencies. Dutch governments are imposing further restrictions on the housing market that are deepening supply distortions. The state already dictates the character of new constructions. For example, in Amsterdam, new housing must be 40% social housing, 40% middle-income and just 20% high-end. A new law passed this year expanded rent control to over 96% of existing units. The Netherlands now has the highest share of rent-controlled units in the OECD. Another provision bans short-term leases entirely. As a result, investors are freezing or decreasing their rental portfolios. New permits are down compared to two years ago.

All the above have combined into a dangerous feed-back loop that is driving radicalism and slowing growth. Buyers now need to earn more than double the median income to be able to afford the average home. As the housing situation deteriorates due to excessive regulation, the demand for new regulation to protect vulnerable inhabitants increases, further weakening supply.

The ASML story has a (for now) happy ending. After it threatened to depart earlier this year, the Dutch government intervened in its favor, with announced investments worth $2.5 billion, and a commitment to build more housing, better infrastructure in Eindhoven, and new transit.9

This decision to help ASML is certainly a good thing, but not all firms have its muscle. The same regulations that inhibited the growth of ASML chafe at thousands of smaller firms that do not have the clout to lobby for resources.

The Netherlands is not full

Instead of stopgap solutions that subsidize demand and further increase scarcity (e.g. the Draghi report's only proposed housing solution is housing assistance),10 Europe needs to actually tackle the underlying problem, which is that regulations make it close to impossible to build sufficient new homes. The idea that the Netherlands is full is almost universally accepted by the Dutch, but the majority of land is used for agriculture. A country like the Netherlands, and certainly its western half, is better thought of as extremely low density sprawl than as a network of individual cities. As Myers, Bowman and Southwood put it in their essay on ‘the Housing Theory of Everything’:11

‘By historical and global standards, today’s most successful cities in America and other Western countries are astonishingly sparsely populated and sprawling. Haussmann’s Paris, Gaudi’s Barcelona, and the Georgian and Victorian areas of London are much more densely populated than nearly every square mile of the Bay Area and even most of the NYC metro area, other than Manhattan.’

The same could be said for the Netherlands, and many of Europe’s other more innovative regions. Building sufficient housing should be an EU-wide objective.12 If we want to get innovation right, we need to allow for the creation of large, high-density superclusters. The ≈7.5 million people in the Bay Area have created more tech value than the ≈750 million people in all of Europe.

In the UK and the US, which have struggled with severe shortages, the drive to build more has converted into organized movements under the YIMBY banner. In Canada, the shortage has gone so far as to drive a significant political realignment, with younger voters supporting the pro-home-building Canadian conservatives. European policymakers should recognize this as a unique opportunity: building more homes is one of the rare ideas which can be politically expedient, drives significant short-term economic growth, and will help the ailing European tech sector.

References

Couwenbergh, P. "ASML-topman: 'Nederland mist visie en is zelfvoldaan'." Financieel Dagblad (2023).

De la Roca, J., & Puga, D. (2017). Learning by working in big cities. Review of Economic Studies, 84(1), 106-142.

Draghi, Mario. 2024a. "EU Competitiveness: A competitiveness strategy for Europe" EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Draghi, Mario. 2024b. "EU Competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations" EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Giusti, Marianna. "Extreme renting: Estonia start-up boom fuels EU's biggest cost rises." Financial Times (2023).

Glaeser, Edward L., and Joshua D. Gottlieb. "The wealth of cities: Agglomeration economies and spatial equilibrium in the United States." Journal of Economic Literature 47, no. 4 (2009): 983-1028.

de Graaf, P. "ASML gaat van groot-groter-grootst." de Volkskrant (2024).

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Enrico Moretti. "Housing constraints and spatial misallocation." American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11, no. 2 (2019): 1-39.

Myers, J., Bowman, S., & Southwood, B. "The housing theory of everything." Works in Progress (2021).

RTL Z. "ASML hekelt migratieplannen NSC en PVV: 'Krijgen we hier geen mensen, dan wel elders'." RTL Nieuws (2024).

The appendix mentions it a further four times. The concept of superclusters is discussed repeatedly within discussion of innovation.

Glaeser, Edward L., and Joshua D. Gottlieb. "The wealth of cities: Agglomeration economies and spatial equilibrium in the United States." Journal of Economic Literature 47, no. 4 (2009): 983-1028.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Enrico Moretti. "Housing constraints and spatial misallocation." American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11, no. 2 (2019): 1-39.

De la Roca, J., & Puga, D. (2017). Learning by working in big cities. Review of Economic Studies, 84(1), 106-142.

Giusti, Marianna. "Extreme renting: Estonia start-up boom fuels EU's biggest cost rises." Financial Times (2023).

A number of other factors contributed. The new coalition wants to decrease migration, including by lowering the number of international students in Dutch higher education, and lower tax benefits for expats. All are anathema to ASML.

RTL Z. "ASML hekelt migratieplannen NSC en PVV: 'Krijgen we hier geen mensen, dan wel elders'." RTL Nieuws (2024).

Couwenbergh, P. "ASML-topman: 'Nederland mist visie en is zelfvoldaan'." Financieel Dagblad (2023).

de Graaf, P. "ASML gaat van groot-groter-grootst." de Volkskrant (2024).

Draghi, Mario. 2024. "EU Competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations." EU Commission: 275.https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Myers, J., Bowman, S., & Southwood, B. "The housing theory of everything." Works in Progress (2021).

In fact, sufficient housing can go as far as helping reach convergence goals by enabling low-skill outmigration from less productive areas.