In the depths of the COVID pandemic, with the ECB committed to keeping sovereign spreads low and the EU fiscal rules suspended, Italy launched what would become one of the costliest fiscal experiments in history. Prime Minister Conte announced that the government would subsidize 110% of the cost of housing renovations. The “SuperBonus,” as the policy was called, would improve energy efficiency and stimulate an economy that had barely grown in over two decades. Consumers would face neither economic nor liquidity constraints:

In the construction sector we will introduce a Superbonus for the home: everyone will be able to renovate their homes to make them greener. You will not spend a penny for these renovations. (Giuseppe Conte, May 13, 2020).

The state would pay homeowners 110% of the cost of renovating their properties through an innovative financial mechanism: rather than direct cash grants, the government issued tax credits that could be transferred. A homeowner could claim these credits directly against their taxes, have contractors claim them against invoices, or sell them to banks. These credits became a kind of fiscal currency – a parallel financial instrument that functioned as off-the-books debt (Capone and Stagnaro, 2024). The setup purposefully created the illusion of a free lunch: it hid the cost to the government, as for European accounting purposes the credits would show up only as lost tax revenue rather than new spending.

The SuperBonus created the conditions for what Draghi's Minister of Economy Daniele Franco called “one of the largest frauds in the history of the Republic ” (Capone and Stagnaro, 2024). Contractors often inflated renovation costs; for instance, a €50,000 project might be reported as €100,000. The bank would purchase the €110,000 tax credit at near face value, enabling the contractor to pocket the difference, sometimes sharing it with the homeowner. At times, no work at all was carried out, in which case, invoices for non-existent work on fake buildings were a perfect tool for organized financial crime. Fraudulent credits could then be resold multiple times in an unregulated market of state-backed tax discounts. In 2023, authorities estimated that such fraudulent activities had cost taxpayers €15 billion.

By 2024, it was clear that the lunch was, of course, anything but free. Builders were going around offering to pay people money to renovate their houses. A scheme initially budgeted at €35 billion will end up costing Italian taxpayers €220 billion (€160 billion of Superbonus + €60 billion for the 90% facade restoration credit and other 65% credits) — about 12% of GDP.1 Annual costs ballooned from 1% of GDP in 2021, to 3% in 2022, and 4% in 2023. Only 495,717 dwellings would end up being renovated – meaning the average cost of the program was around €320,000 per home. 2This occurred in a country already burdened with debt of 140% of GDP, facing massive unfunded pension liabilities of over 400% of GDP, and whose debt is rated at Baa3 by Moodys — one notch above "junk" status. The cost dwarfs the €71 billion in grants Italy received from the European Union's Recovery and Resilience plan. Despite limited coverage in the international press, the Superbonus is easily one of the costliest fiscal errors in history.

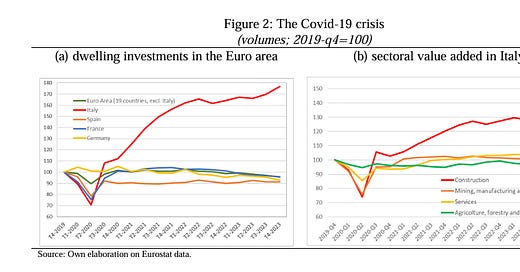

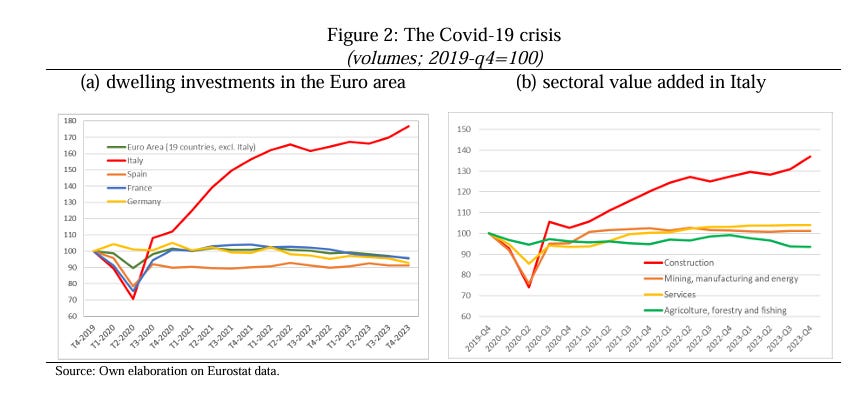

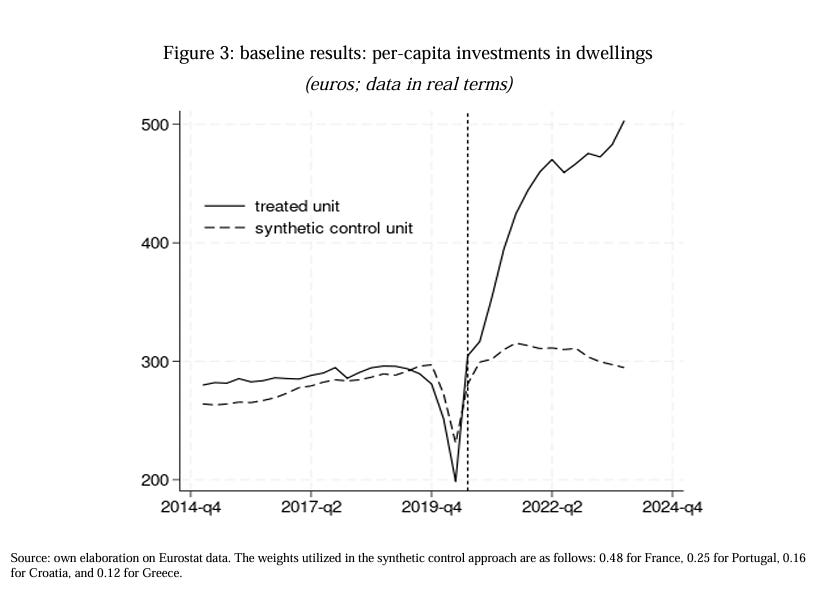

Two recent Banca d'Italia papers and an IMF Mission analyzed the impact of the program. While real dwelling investments per capita did surge 67% above a “synthetic” comparable country, Accetturo, Olivieri, and Renzi (2024) concluded that “the benefits for the economy as a whole in terms of value added were lower than the costs of the subsidies.” Construction costs sharply increased – the Construction Cost Index grew by roughly 20% after the pandemic and surged another 13% after September 2021, with the Superbonus directly responsible for about 7 percentage points of that rise, according to Corsello and Ercolani (2024). The price of setting up scaffolding, an essential first step for renovation, increased by 400% by the end of 2021.

The IMF evaluation is even more critical. The growth stimulus was "fairly limited relative to the size of fiscal resources expended," it concluded, citing "leakage into imports, sizable invoice discounting, increased price markups in construction, crowding out of other investments, and misuse of public funds." Meanwhile, construction employment had entered a boom-bust cycle as firms expanded to capture subsidies, then faced a cliff when the program began winding down.

Even the program's environmental benefits came at an astronomical cost – any calculation will yield far north of €1,000 per ton of carbon saved (versus an ETS Carbon price of around €80 per ton). While the Superbonus was presented as a major operation of energy efficiency and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, it was the largest single instance of greenwashing of our time.

How did it happen?

The SuperBonus emerged in a moment of transformation in economic policy thinking on both sides of the Atlantic.

Riccardo Fraccaro – a lawyer, Five Star Movement politician, Modern Monetary Theory adherent and architect of the SuperBonus – saw the program as a way to push a fiscal expansion while complying with EU rules. By designing the Superbonus as a system of transferable tax credits, Fraccaro and his advisors sought to create a parallel financial instrument that did not immediately register as public debt (Capone and Carlo Stagnaro, 2025).3

Italy’s program embodied the zeitgeist of debt as a driver for growth. It would be partially funded (roughly €13.95bn) through the European 750bn bond issuance under NextGenerationEU. Like Bidenomics in the U.S., it promised to simultaneously achieve multiple transformative goals: economic stimulus, social equity, and environmental protection. And like many post-pandemic programs, it reflected a belief that past policies had been too timid and that traditional budget constraints could be safely ignored in pursuit of broader social objectives.

Once started, the Superbonus proved politically impossible to stop. The benefits were concentrated among vocal constituencies: homeowners getting renovations, the environmental movement, and contractors seeing booming business. The costs, while enormous, were spread across all taxpayers and pushed into the future through the tax credit mechanism. No government—leftist, technocratic, or right-wing—was able to resist its logic. Parliament consistently pushed back against efforts to limit its scope, even after fraud estimates hit €16 billion. As prime minister, Mario Draghi, despite publicly criticizing the program for tripling construction costs, could not halt it — in fact, his initial action was to simplify access to it. When his government attempted to curb abuse, the Five Star Movement reacted with anger, and even modest controls on credit transfers were fought. By 2023, Giorgia Meloni's right-wing government faced the same constraints—industry groups protested, coalition partners balked. Economy Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti warned colleagues, “I fear you do not understand the gravity of the situation.”

Still, it is not just Italian politics that should have put a stop to this. Besides parliament, there are two potential mechanisms to avoid such fiscal adventurism in a country already burdened with one of Europe's highest debt loads. First, the fiscal rules and the European Commission. Second, the market, the so-called bond vigilantes. Both failed.

The fiscal rules were suspended because of Covid. But this does not absolve the European Commission, which is in charge of those rules, of responsibility. The Recovery and Resilience Facility (the EU-wide Covid recovery fund) was designed with strict conditionality, ensuring that funds were disbursed only after member states met milestones on reforms and complied with “European semester” recommendations. The European Commission was ordered to review national recovery plans, verify compliance with structural objectives, and withhold payments if conditions were not met. In the case of Italy’s Superbonus, this mechanism failed.

The Commission approved the inclusion of the Superbonus in Italy’s NRRP after its design, with full knowledge of the fact this program included a 110% subsidy. When the program then ballooned far beyond the EU-approved scope, transforming into a massive fiscal liability without oversight, the Commission allowed funds to continue to flow. Even as Italy's deficit projections spiraled out of control, it failed to recognize or deliberately ignored that the Superbonus had become an unchecked vehicle for waste and fraud, undermining the point of the RRF’s milestone-based disbursement system.

That leaves the bond vigilantes. But, as John Cochrane, Klaus Masuch and I argue in our forthcoming book “Crisis Cycle:” with Princeton University Press, thanks to the ECB's implicit guarantee Italian policymakers are unconstrained by markets. They could reasonably expect (and Capone and Stagnaro, 2024 argue they did) that:

The ECB would prevent any major spike in borrowing costs through its bond-buying programs.

The fiscal cost could be obscured by spreading it over years through tax credits.

If market pressure emerged, the ECB would intervene to buy Italian bonds.

This calculation proved correct. When Italy's deficit shot up in 2023 due to the Superbonus, rising from a projected 5.5% to 8% of GDP, there was no market panic. Italian bond spreads remained contained, thanks to the ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which reassured investors without the ECB even needing to intervene. By removing the constraint of market discipline, the ECB allowed the Superbonus to persist far longer than it otherwise would have.

Not all future programs will be as egregious as the Superbonus – which is quite possibly one of the dumbest fiscal policies in recent memory. As the Italian General Accounting Office put it in its 2024 retrospective, "The Superbonus was significantly different from previous benefits whose effects were known. For the first time, full coverage of costs was allowed, increasing the attractiveness of the measure and substantially eliminating the conflict of interest between suppliers and buyers."

But the Superbonus illustrates a deeper problem facing Europe: the traditional mechanisms for fiscal discipline have broken down. Market forces (the bond buyers) have been neutralized by ECB intervention. The European Commission's fiscal rules, already weakened by repeated violations from large countries like France and Germany, are being replaced by new rules that, since they rely on bilateral bargaining, provide little real constraint. And domestic political systems, freed from market pressure, increasingly treat debt-financed spending as a free lunch.

This erosion of discipline isn't limited to Italy. France's deficit has drifted to 6.1% of GDP. Spain reversed its post crisis pension reform right around the time Italy was passing the Superbonus, with much larger negative consequences for fiscal sustainability. In a world where the ECB will always intervene to prevent bond market pressure and Brussels cannot credibly enforce fiscal rules on large states, sustainable fiscal policy becomes politically almost impossible.

The very mechanisms designed to protect the euro may now be undermining it. When the ECB steps in to prevent market pressure on sovereign bonds, it removes a crucial disciplining force on national fiscal policies, creating perverse incentives for politicians to expand spending without regard for long-term sustainability. A currency union without fiscal union can only work if member states maintain sustainable spending policies. But Europe now finds itself caught in a trap of its own making: its crisis-fighting tools are steadily eroding the discipline necessary for the euro's survival. Until Europe finds a way to restore meaningful constraints on national spending policies while preserving financial stability, each "temporary" expansion of spending risks will become permanent, each "one-time" intervention by the ECB risks becoming routine, and the underlying tensions in the monetary union will continue to build. My forthcoming book (with Cochrane and Masuch) proposes how to fix this state of affairs.

References.

Accetturo, Antonio, Elisabetta Olivieri, and Fabrizio Renzi. Incentives for dwelling renovations: evidence from a large fiscal programme. No. 860. Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area, 2024.

Capone, Luciano and Carlo Stagnaro. “”Superbonus: Come Fallisce una Nazione”, Rubbettino Editore (November, 2024).

Capone, Luciano and Carlo Stagnaro. Bad ideas have bad consequences: Italy’s Superbonus and the influx of MMT. Mimeo, February 2025.

Cochrane, John, Luis Garicano and Klaus Masuch. “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro” Princeton University Press, Forthcoming (June 2025).

Corsello, Francesco, and Valerio Ercolani. The role of the Superbonus in the growth of Italian construction costs. No. 903. Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area, 2024.

Eurostat (2023a). Manual on Government Deficit and Debt – Implementation of ESA 2010. 2022 Edition. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Part of the reason for the surprise relative to expectations is that the Ministry of Finance had not modelled the behavioural response by consumers to the credit. Unlike the Ministry, Luciano Capone, a journalist for Il Foglio (and the author of a book detailing the program history), understood the perverse incentives from the start, warning in May 2020: “The customers will not go around asking builders for a discount but–on the contrary–an increase in price.” Incentives do matter.

The Super Bonus in a narrow sense was €160bn (the other €60bn are the facade restoration credit and other credits, as explained in the text. If there were 500,000 dwellings, the average renovation received €320,000 subsidy.

Here is the explanation of the accounting issue by Capone and Stagnaro (2025): “Non-payable tax credits “are treated as negative tax revenue and not as expenditure, they will be recorded when they are used to reduce the tax liability, impacting the accounts for the exact amount used each year,” (Eurostat, 2023: 88). However, if the tax credit is transferable (as the Superbonus was “if the tax credit can be transferred to third parties, such tax credit is thus to be deemed as a payable tax credit and has to be recorded in national accounts as an asset of the taxpayer and a liability of government” (Eurostat, 2023: 86).”

Great piece. Reading pieces like this always makes me fomo about missing out on the fraud.

Never understood why people follow American politics so closely when Italian politics is clearly more entertaining.