On April 11th and 12, EU finance ministers will meet in Warsaw to discuss how Europe should pay for its defense.

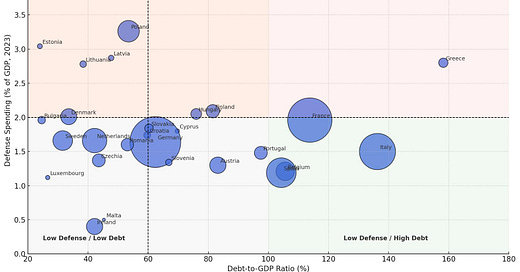

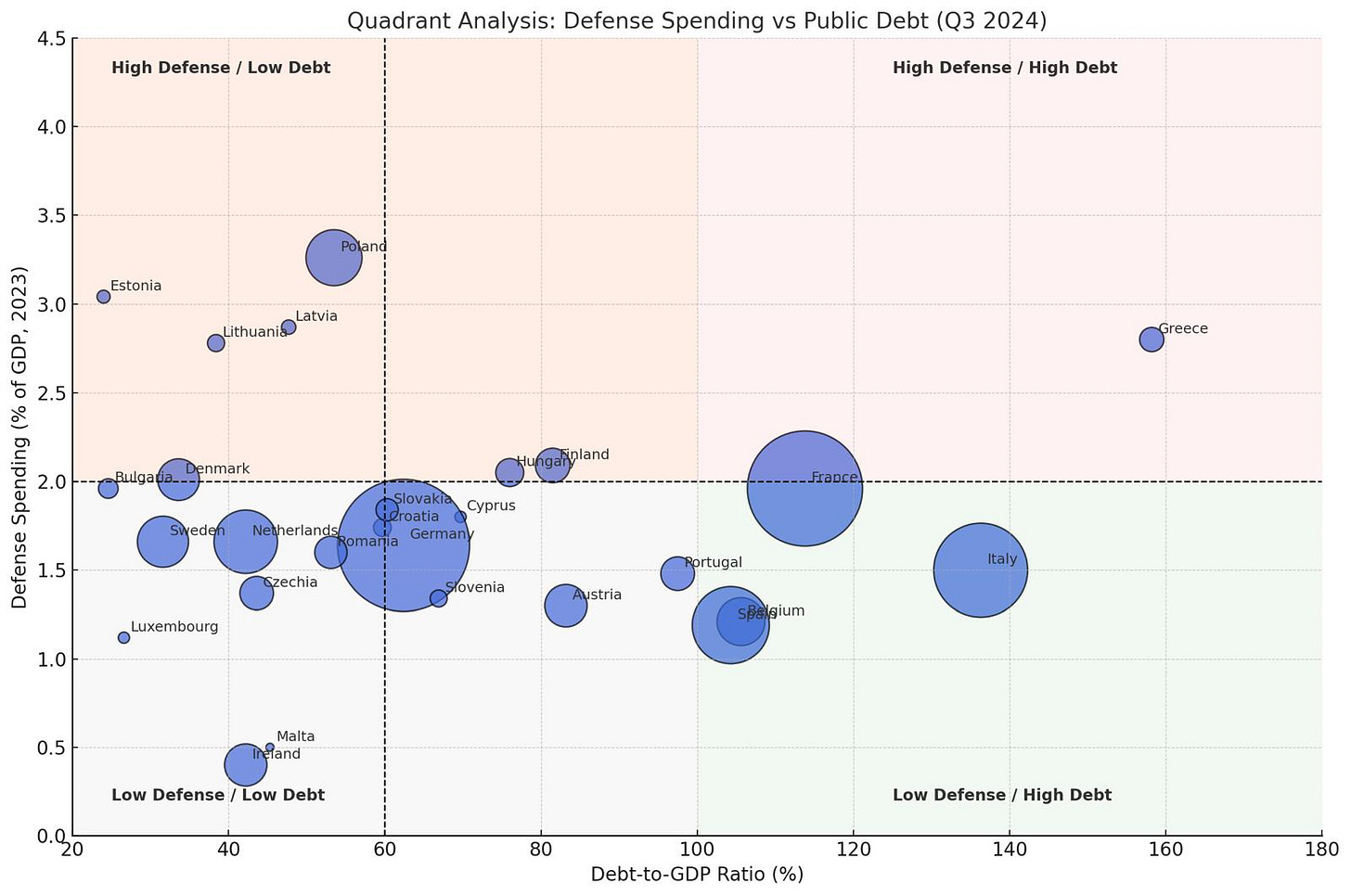

Unfortunately, the European Commission's proposal that is supposed to add €800bn in defense spending is magical thinking. Of the €800 billion, €650 billion is money that the member states are supposed to raise through normal bond issuances thanks to relaxed EU debt rules. In reality, this won’t lead to anything like €650 billion in new spending. Many nations are already operating within EU budget limits (like the Netherlands, Sweden, and Ireland), so the EU budget rules are not binding for them. Meanwhile, the more indebted countries (France, Spain, and Italy) face market pressure rather than EU constraints and appear unable to significantly increase defense spending just because EU rules are loosened.

The other component of the plan is a €150 billion loan fund called SAFE for states to borrow for defense purchases. SAFE works as a middleman borrower. It raises money at an interest rate that (roughly) averages what EU countries pay, then lends this money to individual countries at that same average rate. This creates minimal benefits — none to highly rated EU sovereigns (who will prefer borrowing on their own) and a small amount (in the low tens of millions for France and Italy) in interest to the lower-rated ones.

The Commission's plan fails to address a fundamental problem: European nations spend defense money inefficiently. The reason is the importance of scale in defense, and hence the key role played by unified procurement.

Three economic factors make scale critical for effective defense spending.

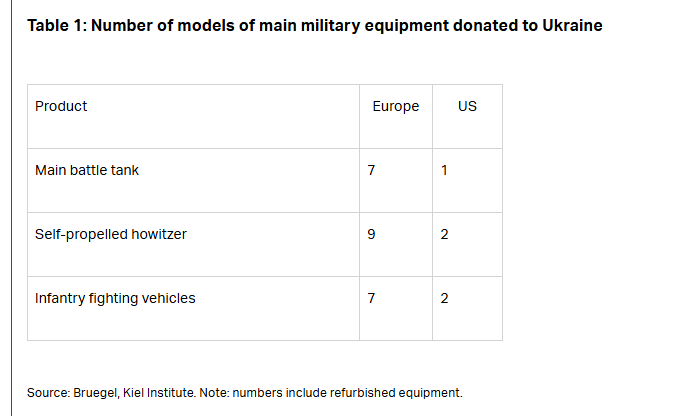

First, defense production inherently benefits from economies of scale due to high fixed costs in research, development, and production setup. When Europe maintains multiple parallel systems –12 different tank models compared to one in the United States – each country bears these fixed costs separately, reducing the purchasing power of every euro spent. Each small production run prevents manufacturers from moving down the cost curve.

Second, critical defense assets like radar networks, satellite communications, and ballistic missile defense that serve as ‘strategic enablers’ have economics similar to software platforms. Once deployed, they serve additional users at minimal cost while their value increases exponentially with scale – each new radar station not only extends coverage but enhances the entire system's effectiveness through better triangulation and redundancy.

Third, military production benefits from significant learning curves, with unit costs falling 10-15% each time cumulative production doubles. Joint purchasing could potentially cut unit costs in half by dramatically increasing production volumes.

Europe needs a non-magic plan that deals with the reality of tight budgets and solves the basic problem of attaining minimum efficient scale in defense. A recent proposal by a Bruegel team (Wolff, Steinbach, and Zettelmeyer, 2025) may offer such a solution.

The European Defense Mechanism

Wulff et al. (2025) propose a European Defense Mechanism (EDM), set up by an intergovernmental treaty between governments. The objective is to transform how Europe funds and purchases defense capabilities.

This new institution (EDM) would:

Collectively procure weapons systems with high upfront costs. The treaty would specifically define areas requiring joint procurement, with enforcement mechanisms including potential suspension for non-compliance

Create a true defense single market, prohibiting procurement discrimination based on nationality and banning state aid for companies that discriminate, with violations potentially resulting in membership suspension

Own and operate critical defense assets (the strategic enablers like radars and missile defenses) that benefit all members, with countries paying usage fees rather than bearing full upfront costs, while including key non-EU partners like the UK and Norway. This is the most radical part of the proposal, but also its most essential – these are the systems that fall away entirely upon US withdrawal.

Include the UK, Norway, Ukraine, and potentially other European democracies as equal partners, while excluding EU countries that are either (legally) neutral (Austria, Ireland), or actively allied with our enemies (Hungary).

Be governed by (weighted) majority voting based on members’ capital contributions, with voluntary membership but binding commitments once joined.

This proposal builds on lessons from the eurozone's repeated difficulties (which I analyze in my forthcoming book with John Cochrane and Klaus Masuch, “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro”). Just as the eurozone needed mechanisms to manage collective fiscal risks and solve incentive problems, European defense requires a structure to overcome collective action problems. Both need intergovernmental bodies with dedicated mandates (sovereign crisis management vs. defence procurement/funding), independent financing capacity, and rules designed to address collective action problems and moral hazard inherent in multinational cooperation.

Technical solutions to political problems

The EDM proposal is ambitious but finds a clever way around some of the major obstacles to defense cooperation. These obstacles derive from the desire to pool the sovereignty of states in the area where they guard it most jealously.

Eurocrats (and I have been guilty of this) are used to drafting seemingly technical documents that sidestep the knotty political issues that are at the root of integration. The EDM's design intentionally avoids the full pooling of sovereignty that a European Defense Union would require, focusing instead on procurement and shared infrastructure.

This division is workable. NATO has operated for decades with a similar separation — common standards and some shared assets, but national control over deployment decisions. What the EDM adds is deeper integration on the procurement side to achieve the economic efficiencies NATO has failed to deliver, while respecting the political reality that deployment decisions must remain with national parliaments.

However, even this limited approach must address several trust concerns:

First, what happens if a member state undergoes political change and aligns with a potential adversary – say Le Pen takes power in France or the AfD in Germany? The EDM proposal partially addresses this by maintaining ownership of critical assets rather than transferring them to national militaries. A country violating its commitments could lose access to satellite intelligence, air defense networks, or communications systems based on a majority vote. Ensuring the paid upfront capital is large seems an additional possible way to reduce the risk of hold-ups.

Second, countries might attempt to minimize their contributions while benefiting from the security provided by others – a problem familiar from Eurozone fiscal debates. The weighted voting system gives larger contributors greater influence but cannot eliminate free-riding (see Spain's, my own country, current attempt to reclassify environmental and transport spending as defense).

Third, perhaps the most fundamental challenge: during a severe crisis, would all EDM members honor their obligations? Unlike the previous concerns, this risk cannot be fully mitigated by institutional design. While the EDM focuses on procurement rather than operations, joint ownership of strategic assets and reliance on weapons manufacturers outside the nation-state creates mutual dependencies that some countries might find uncomfortable in extreme situations. This remains an inherent tension in any multinational defense arrangement short of political union.

The EDM represents a pragmatic middle path – more integrated than the current fragmented system but less centralized than a full defense union. It replaces abstract trust with contractual obligations, shared dependencies, and financial incentives (again, like the institutional approach advocated in our book to manage Eurozone interdependencies).

Most importantly, the EDM creates structures where countries' interests progressively align through cooperation. As defense industrial bases integrate, joint procurement becomes standard, and strategic assets operate across borders, the practical cost of non-cooperation increases. Trust develops through successful collaboration rather than political declarations.

The EDM is the best way forward.

Europe's defense financing challenge won't be solved by accounting gimmicks or interest rate subsidies. The fundamental problem is structural inefficiency and fragmentation that wastes resources and diminishes capabilities. The European Defense Mechanism offers a realistic path forward, combining fiscal flexibility with the transformative benefits of a true defense single market. While establishing such an institution would face political obstacles, the alternative - continuing Europe's inefficient, fragmented approach to defense - poses far greater risks in an increasingly dangerous world.

While the EDM cannot resolve all of Europe's defense challenges, particularly those related to trust, political will, and national sovereignty in military affairs, it creates institutional incentives for cooperation that can build the confidence needed for deeper integration. We face this challenge because the US, whom European nations have relied on for our protection for 80 years, no longer wants to be trusted. In a world of limited resources, the European Defense Mechanism is the most efficient path towards defense autonomy.

Sources

Cochrane, John H., Luis Garicano, and Klaus Masuch. “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro.” Princeton University Press. Forthcoming.

Wolff, Guntram B., Armin Steinbach, and Jeromin Zettelmayer, “The governance and funding of European rearmament.” Bruegel Policy Brief.

Wolff, Guntram B., Alexandr Burilkov, Katelyn Bushnell, Ivan Kharitonov. “Fit for war in decades: Europe’s and Germany’s slow rearmament vis-a-vis Russia, Kiel Report 1, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/fit-for-war-in-decades-europes-and-germanys-slow-rearmament-vis-a-vis-russia-33234/ Policy Brief. 07 April 2025.

Excellent post. It is clear that the excessive variety of models in all defense platforms (MBT, subs, frigates, howitzers, etc.) is a waste of resources. And that without the strategic enablers (i.e., without the USA) European armies become substitutes, not complementary to each other.

I also agree that it is better to aim for a pragmatic middle way than to aim (and fail) for a political union on defense matters. As an example, during the worst war so far (WWI), it took the Entente until March 1918 (!) to appoint Foch as Supreme Allied Commander, and they had fewer countries to coordinate.

Interesting piece Luis. I am sure you are right that the EDM proposal is the most pragmatic middle way available given current political constraints. But it is surely very much second best. It creates yet another issuer of common European debt underpinned by its own unique guarantees to add to the various other varieties of common debt already in the market. Yet the geoeconomic imperative for the EU right now, even more so in the light of Trump’s assault on the credibility of the dollar, is surely to create a deep pool of common European debt with the same funding structure to create a safe asset that the market can readily understand and absorb. For that reason, I would have thought that a key consideration in the design of any inter-governmental EDM is that it can be readily brought within the treaties as soon as circumstances allow as was the case with the ESM. But that would of course mean excluding the UK, Norway and Ukraine. Quite a problem…