The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was supposed to be Europe's big move to protect consumer privacy and reassert its technological relevance. But mounting evidence —including a critical paragraph in the recent Draghi (2024a) report— suggests it is doing more harm than good to Europe's tech ecosystem. Let's break this down.

Is the pursuit of the “Brussels effect” damaging EU tech firms?

The "Brussels Effect," coined by Anu Bradford in a 2012 paper (and later a 2020 book of the same title) says that when the EU makes rules, because its market is so large, companies around the world will decide it's easier to just follow those rules everywhere rather than trying to have different rules for different places. The idea is inspired by what happens in the US with the spread of California rules, the “California effect”. It's like when your vegetarian friend comes to dinner: you make the whole meal vegetarian because it's easier than cooking two separate meals.

Obviously, this argument is very appealing to EU bureaucrats and EU parliamentarians (yes, mea culpa, I was one of them). You get to set the rules for everyone!

But does this make EU firms more competitive, or does it just increase their compliance costs? Maybe it’s a mixed bag: Brussels could be the world’s cop on green issues, while bogging down its own firms in tech. So let’s talk GDPR.

The duties imposed by the GDPR

GDPR is the big data privacy law enacted by the European Union in May 2018. It aimed to protect individuals' personal data and privacy by setting strict rules on data collection, processing, and storage. GDPR applies to all organizations handling EU residents' data, regardless of location.

GDPR requires firms to get clear consent before using personal data. If ensures data is used only for the purpose it was collected, and only minimum data, for minimum time, is held. It sets stringent rules for special categories of data, like health or demographics. It allows people to see what data companies hold about them, correct it, or ask for its deletion. Firms must report data breaches quickly, minimize the data collected and not use it beyond the purpose of collection. Fines for breaches can reach 4% of global revenue.

As an EU consumer, my overwhelming reaction to these rules was positive. I like it that my data is not flowing around out of control, that it needs to be processed carefully, that my consent is required. I like that I do not have to worry excessively about my privacy. I am relieved to know these rules apply. But for EU firms trying to compete globally, the picture is less rosy.

The Hidden Costs of GDPR for firms

We would expect three main types of impact from a law structured as GDPR:

Higher process costs: GDPR increases the cost of processing transactions — this is the direct cost for firms of complying. Survey evidence suggests costs ranging from $1.3 million for small companies to $70 million for larger ones. Structural estimates suggest that GDPR made data storage 20% more costly for EU firms.

Higher market reach and matching costs: We would expect GDPR to reduce the matching probability — the chance that someone is served a good ad, or finds the right buyer or seller for a product — as the information available and the number of data points available (e.g., buyers and sellers that can be contacted with a cold call or a targeted ad) is reduced by their need to provide consent.

Fragmentation of the single market: GDPR, which should induce a harmonized, EU wide approach, allows Member States to define privacy rules in 15 areas, leading to ambiguity in enforcement and fragmentation of the single market. According to Draghi (2024a) there are “around 100 tech-focused laws and more than 270 regulators active in digital networks across all Member States”.

Consistently with these costs, the evidence shows several unintended effects of GDPR for EU firms :

Web traffic and online tracking fell by 10-15% after GDPR began. Users often opt out when asked for consent. EU firms store 26% less data on average than US firms two years after the GDPR and reduce computation relative to US firms by 15%.

The market has become more concentrated. Large firms with their own data gained market share. Small firms struggle more to comply and reach customers than large ones.

Innovation has slowed. New app entries in the Google Play Store halved after GDPR. Venture capital deals in the EU fell by 26.1% compared to the US. In particular AI innovation in Europe has been hindered- GDPR increase the cost of storing and processing the data required to train AI models

Let's break down 2 and 3.

Big Firms Win, Small Firms Lose

It appears GDPR has put smaller firms at a relative disadvantage and that it has increased market concentration, particularly benefiting very large firms, notably Google.

The reason is that GDPR increases the fixed costs of data manipulation, and hence creates new economies of scale – and advantages for large firms. It's like telling everyone they need to buy a $1 million machine to make cookies. Google can afford that, but your local bakery? Moreover, it gives an advantage to those who have large proprietary (first party) data sets and hence can more easily contact customers.

An anecdote may help to illustrate this point: while writing this blog, I talked to a small Spanish B2B company which used to have a contact database of 300,000 firms. The day GDPR started, that dropped to 15,000 because they needed explicit consent.

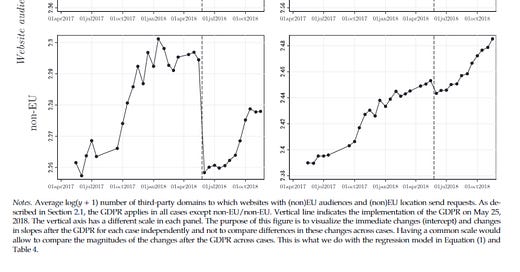

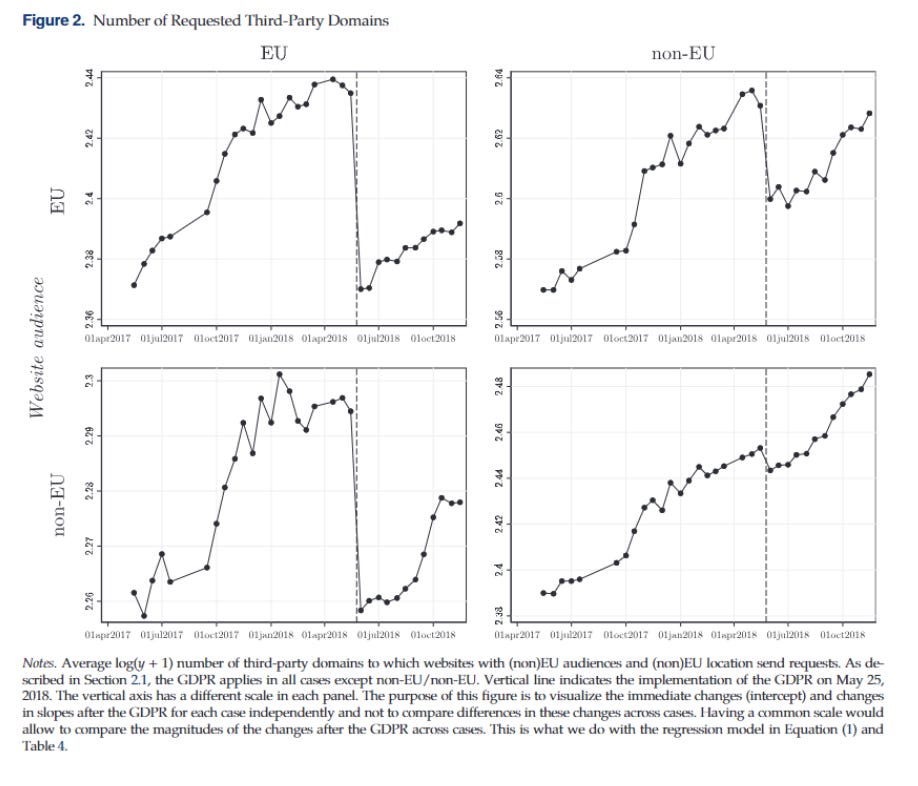

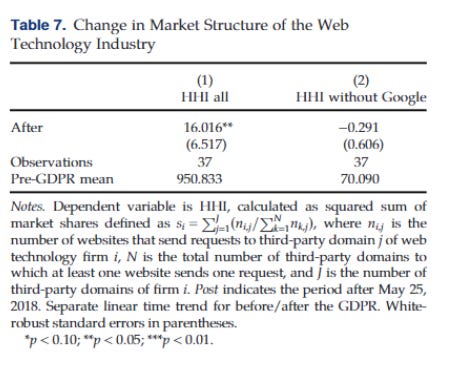

The systematic evidence seems to point in the same direction as that anecdote: according to Peuker et al (2022) and others, although the market for web tech services overall is reduced, and hence all firms suffer losses, the largest firm—Google—loses relatively less and significantly increases market share in important markets such as advertising—Google’s increasing share single-handedly contributes to increasing market concentration (see Table 7 from Peukert et al (2022 and Figure 2 below). Hence, as they put it, “privacy regulation may have unintended consequences for market structure and competition”.

Also Johnson et al (2023), find that (given the 15% drop in website use of web technology vendors discussed above) top vendors were more likely to be retained, increasing market concentration by 17%. Facebook and Google were the main beneficiaries, both increasing their market shares. While these effects lessened over time, they persisted in the category most important to regulators. Similar effects are found by Aridor et al. (2023).

Less Innovation, Fewer Entrants

We would expect the two effects discussed above, more bureaucracy and less market reach, to make life difficult for new entrants and innovators: because of the increased economies of scale (due to the need to invest in data processing capability and bureaucracy) , entrants are at a disadvantage, as well as small incumbents; this also results because the access to first party data creates a significant incumbency advantage. Indeed, it appears that GDPR has reduced product entry and venture capital investment.

According to Janssen et al (2022), GDPR induced the exit of about a third of available apps; in the quarters following implementation, entry of new apps fell by half. Also, average users per app rose by about a quarter for apps born after the imposition of GDPR. Finally, consistently with the objective of the regulation, apps became somewhat less intrusive after GDPR.

More worryingly, GDPR appears to reduce (Jia et al, 2021) the number of venture deals in the EU compared to the USA and RoW following GDPR's rollout in May 2018. The EU experienced a 26.1% reduction in the number of monthly venture deals compared to the USA, and a 34.2% reduction compared to the RoW. The negative effects were larger for consumer-facing ventures (B2C) than B2B ones for and those more reliant on data. B2C ventures saw a reduction of up to 17.6% in monthly deals compared to the USA, and data-intensive ventures experienced reductions of about 31% in the EU compared to both the USA and RoW. Business-to-business (B2B) ventures were less affected but still saw a notable decline post-GDPR. Early-stage and younger firms (0-3 years old) were disproportionately impacted, with EU early-stage deals dropping by 34% relative to the USA and deals involving young firms declining by 30.3%.

The risk to innovation is particularly worrying in the case of AI. From the start of GDPR, it was feared that some of its main concepts would be incompatible with data processing and storage necessary for AI. For instance, Zarsky (2017) argues that Purpose Specification (art 5.1. (b)), (the obligation for the data to be collected for a particular purpose and only is clearly used for that purpose) is incompatible with big data analysis, which involves usage patterns not even imagined by the subject or use. There is a statistical purpose exception, but it is narrowly defined. Similarly , the Data Minimization principle (5.1. (c)), which allows only data necessary to the purpose sought, and limits the duration of the collection, similarly curves AI research and statistical learning. Zarsky describes other limits placed by “special categories” (art 9, which provides for an expensive additional regime for some data classes , such as health genetic, racial, ethnic, political opinions etc.) and automated decisions (art 22, for decision making processes which are fully automated, and allows the individual to not be subject to those decisions). The recent Draghi (2024a) report concludes that “limitations on data storing and processing create high compliance costs and hinder the creation of large, integrated data sets for training AI models. This fragmentation puts EU companies at a disadvantage relative to the US, which relies on the private sector to build vast data sets, and China, which can leverage its central institutions for data aggregation”.

Making Privacy and Innovation Compatible

So, how does GDPR measure up? It has definitely spread privacy norms around the world. That's the intended Brussels Effect. But there's also an unintended Brussels Effect: GDPR appears to be making it harder to start and scale EU tech firms, and for firms to store data and to process information. And it appears to be benefitting the two companies (Google and Facebook) that EU regulators claim to be most concerned about. This is proving particularly damaging to the EU at the start of the AI era, since data storage and processing are purposely made more difficult by GDPR.

What should EU regulators and policymakers do? What is the task of the new EU Commission and Parliament? The main message is that GDPR is not a given, and that we need to change it and improve it. A concrete revisions to GDPR could be a post on its own, but here are some basic principles and ideas to start the conversation

Stop trying to be the regulator to the world. At least in tech, we are too small to make everyone follow our lead. The Brussels effect only works if we are large. True when we talk about consuming mangoes. Not true when talking about Digital Tech or AI. Align GDPR with Califonia’s CCPA and other global rules.

Revisit GDPR. In particular, the obligations of data minimization and purpose specification need to be curtailed. To the extent that anonymity and privacy can be preserved (e.g. through encryption), AI development requires access to data. To be able to compete, EU firms must be able to access large data sets which are non-proprietary. The alternative is to cede the field to those who have first party data- yes, that would be Google and Meta.

Eliminate fragmentation: GDPR is complicated enough. Hundreds of regulators enforcing hundreds of laws is a killer for innovative firms. We need a Brussels-only approach here. (Of course, the problem is that now we have created 100s of bureaucracies that will fight for their survival).

Tiered compliance: Without creating barriers to firm growth, we must facilitate small firms’ entry and survival e.g. by creating safe harbors for innovation where startups and researchers can experiment with data-driven technologies under relaxed GDPR rules, provided they meet certain ethical standards and transparency requirements.

Undertake policy evaluations of GDPR and other tech regulations: institute mandatory, periodic reviews of GDPR's economic impact, focusing on competition, innovation, and startup entry. Anecdotally, many policymakers in Europe still think of GDPR as a success story, not a failure. The evidence suggests otherwise– at least, for firms, if not consumers — but is limited and poorly disseminated. Use these findings to guide improvements to the regulation.

References

Aridor, Guy, Yeon‐Koo Che, and Tobias Salz. "The effect of privacy regulation on the data industry: empirical evidence from GDPR." The RAND Journal of Economics 54, no. 4 (2023): 695-730.

Aridor, Guy, Yeon-Koo Che, Brett Hollenbeck, Maximilian Kaiser, and Daniel McCarthy. 2024. Evaluating The Impact of Privacy Regulation on E-Commerce Firms: Evidence from Apple’s App Tracking Transparency. MSI Report No. 24-124. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute.

Bradford, Anu. 2012. "The Brussels Effect." Northwestern University Law Review 107 (1): 1-67.

Bradford, Anu. 2020. The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Demirer, Mert, Diego J. Jiménez Hernández, Dean Li, and Sida Peng. Data, privacy laws and firm production: Evidence from the GDPR. No. w32146. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024.

Draghi, Mario. 2024a. “EU Competiveness: A competitiveness strategy for Europe ” EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Draghi, Mario. 2024b. “EU Competiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations” EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Goldberg, Samuel G., Garrett A. Johnson, and Scott K. Shriver. "Regulating privacy online: An economic evaluation of the GDPR." American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 16, no. 1 (2024): 325-358.

Janßen, Rebecca, Reinhold Kesler, Michael E. Kummer, and Joel Waldfogel. 2022. "GDPR and the Lost Generation of Innovative Apps." NBER Working Paper No. 30028. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30028.

Jia, Jian, Ginger Zhe Jin, and Liad Wagman. 2021. "The Short-Run Effects of the General Data Protection Regulation on Technology Venture Investment." Marketing Science. Published March 1, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2020.1271.

Johnson, Garrett A., Scott K. Shriver, and Samuel G. Goldberg (2023) "Privacy & market concentration: Intended & unintended consequences of the GDPR" Management Science, 69(10): 5695-5721.

Kircher, Tobias, and Jens Foerderer. "Does EU-consumer privacy harm financing of US-app-startups? Within-US evidence of cross-EU-effects." In Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), pp. 12-15. 2021.

Godinho de Matos, Miguel, and Idris Adjerid. "Consumer consent and firm targeting after GDPR: The case of a large telecom provider." Management Science 68, no. 5 (2022): 3330-3378.

Peukert, C., Bechtold, S., Batikas, M. and Kretschmer, T., 2022. “Regulatory spillovers and data governance: Evidence from the GDPR.” Marketing Science, 41(4), pp.746-768.

Zarsky, Tal,” Incompatible: The GDPR in the Age of Big Data” . Seton Hall Law Review, Vol. 47, No. 4(2), 2017, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3022646

Maybe this is a chicken and the egg thing. Because the startup ecosystem is less mature in Europe, there is no interest group to push back against the laws. Meta and google have bigger lobbying operations and large employment. Yhr best way to drive change is to get European peoples themselves to push for change. Notice how despite pushback Ireland keeps it's friendly tax structure. The peoples of Europe need to find technology as valuable and then they will fight for it. Yet another Brussels driven initiative is unlikely to change these dynamics. One possibility is for European pension funds to organize as a group as they spend considerable sums in the American tech ecosystem and would probably prefer European ones.