An explanation for why there has been so much more progress in software than anywhere else is that it is one of few areas where firms have been able to experiment and release products unhindered.1 One reason is that for the purposes of the law, software is treated as a service, meaning that malfunctions are not exposed to the same legal risk as products. This week the EU released a rule that ends this freedom. The new Product Liability Directive says:

“Software is a product for the purposes of applying no-fault liability, irrespective of the mode of its supply or usage, and therefore irrespective of whether the software is stored on a device, accessed through a communication network or cloud technologies, or supplied through a software-as-a-service model2

The shift is important. The change makes developers legally liable for defects up to 10 years after the last release, regardless of fault.3 It affects AI in particular: claimants will likely not even need to establish a causal link between an AI system’s operations and the damage caused — if someone is hurt, a judge will presume defectiveness.4

What the rule does is increase risk for start-ups and heighten the danger inherent in experimentation. The problem isn’t that the average company will suffer. Rather that, like many EU rules, it makes it harder to do a radically new thing that could create a superstar firm.

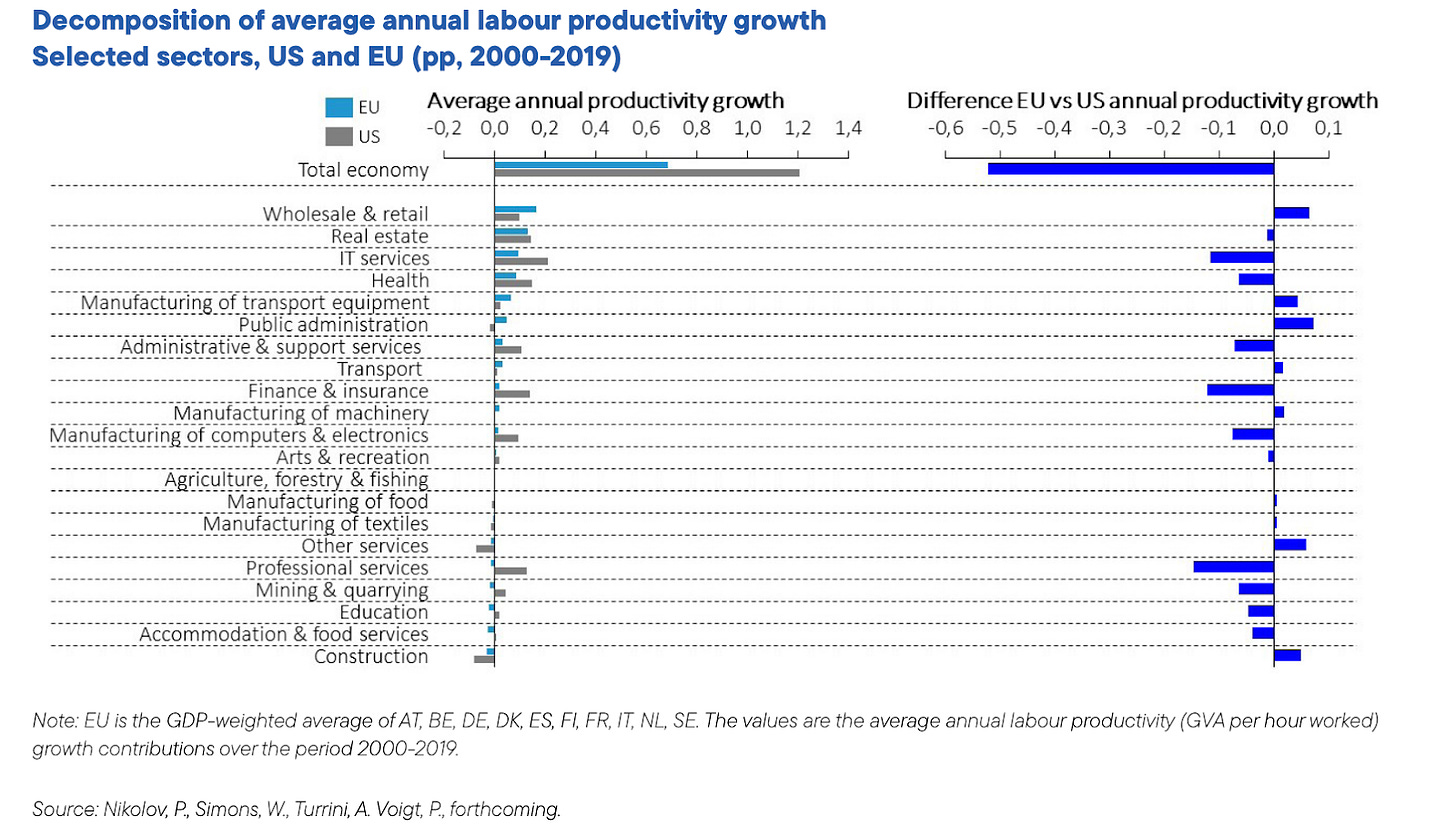

These superstars are much more important than their size would suggest. If, like me, you live in the US, it is sometimes hard to believe that America is so much more competitive. Interactions with banks, insurance firms, car companies, utilities, are painful and worse than in the EU. In many areas — from retail to construction to manufacturing — productivity growth has been higher in Europe.5

Yet, what has America excelled at is creating the world’s superstars.

Consider the following facts:

80% of space cargo is launched by a single company, SpaceX

Up to 95% of AI computing chips are designed by one firm

100% of approved mRNA vaccines have been developed by two firms

The three frontier labs driving progress in AI have around 8000 employees combined — no more than 0.2% of the tech sector

Five firms (Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Apple, and Microsoft) collectively account for almost twice as much R&D as the entire EU public sector.

The ≈7.5 million people in the Bay Area have created more tech value than the ≈750 million people in all of Europe.

Take away the outlier sectors — software, biotechnology and the Musk manufacturing complex (SpaceX, Tesla) — and the American economy indeed does not look that dynamic. Many industries are characterized by stagnant or even declining productivity. But thanks to the superstars, the U.S. is leaving Europe behind.6

The literature provides a number of clear explanations for why the best firms are so impactful:

1. There is imperfect substitution between different levels of performance —you cannot buy 10 cheap phones to compensate for not having an iPhone. Thousands of mediocre ideas do not substitute for one brilliant insight. This means everyone wants to use the best ideas/product.7

2. Innovation and research is characterized by nonrivalry. Everyone can enjoy the fruits of an innovation; one person using a new idea doesn’t prevent another from doing so too. This means everyone can use the best ideas.8

3. Top firms increase the reach of the highest performers. Better leaders are assigned to higher positions, where their abilities have the greatest impact throughout the organization. These effects compound multiplicatively as the best talent clusters with other top performers in the largest firms — maximizing leverage.9

Combined, we get winner-take-all dynamics.

A single focus

If Europe wants to do well at innovation it need to prioritize extreme performance. One heuristic is to apply the following question to every policy:

"What does this do for my outliers? If I have a citizen who is extraordinarily talented and wants to work on a big idea and conquer the universe, am I helping them or am I getting in their way?”

The new EU software product liability directive fails this test. But we can assess many other European policies through this prism:

The education system prioritizes broad-based upskilling rather than developing superstar universities

The EU AI Act and other digital regulations compress the distribution rather than encourage experimentation and risk-taking.

Solvency II's high risk classification of VC investments constrain insurers' venture funding capabilities.10

National regulations for pension funds restrict their exposure to VC, and AIFMD rules that govern funds larger than $500 million restrict VC participation to accredited ‘professional investors’ 11

Bankruptcy rules in Europe mean people remain hindered by failure far longer than in the US.

For some European citizens the gap in the economic outcomes between the United States and the EU is a price worth paying in order to preserve the ‘European way of life’: shorter average worker hours, longer leaves, universal healthcare, better labor and employment protections etc. But if innovation performance is driven by outliers policy may not need to negatively affect the median European.

Look at the example of Israel. In many ways, the Israeli social model is similar to the European one — universal health care, employment protections, unions, public universities — but it has a tech sector that punches far above its weight. It has done this by prioritizing extreme performance in key areas, without sacrificing its broader system:

It has aggressively attracted venture funding, initially matching foreign investments through a government program called Yozma, and exempting foreign VC from capital gains tax. Israel attracted 5.9bn in venture investments in 2022 — three times that of Italy that year.

It has supported a small number of elite research universities that do particularly well in the hard sciences.

It uses its significant defense budget to train technical talent and focus on dual-use R&D, including components, electronics, avionics 12

Government support for firms is market-driven, particularly in the form of ‘sector-neutral’ incubators for early-stage start-ups.13

Its success was not foreordained; in the 1960s Israel spent less on R&D as a share of GDP than any developed nation except Italy. Now, no European country has more NASDAQ-listed companies than Israel.

Israel seemingly maximizes its citizens' abilities to create extremely impactful firms, subject to maintaining on its social model. Some policies — like more flexible labor laws — clearly improve outlier performance, but also increase uncertainty. But other policies — deeper and more unified capital markets, superstar universities, less tech regulation — are able to greatly amplify the right tail while preserving a way of life many citizens value.

Is this enough?

There is an argument that you can't have the right tail without the left. Imagine if a start-up is competing in the global market for some non-rivalrous good. Even if some good policies give the European firm a sizable boost, if they remain 10% behind their competitor, they will lose 100% of the market. In other words, the effects of policies to boost superstars are multiplicative.

The biggest tradeoff is likely labor laws. A recent paper by Yann Coatanlem and Oliver Coste argues that employment laws are hurting the ability of top EU firms to respond to AI.

In the U.S. firms have been decisive:

“The rapid success of ChatGPT triggered immediate responses: Microsoft streamlined its workforce, invested $10 billion in OpenAI, and more in its own AI infrastructure. Meta paused its metaverse efforts, laid off 20,000 employees within months, and boosted its AI investments, spending a whopping $37 billion on computing infrastructure in 2024. 41 Similarly, Google, facing challenges in search, halted major projects, laid off 12,000 employees, and accelerated on AI by ramping up its R&D investments to $43bn in 2023, including hiring tens of thousands of engineers with AI background.”14

While the EU’s tech leaders are struggling to respond:

“In Europe, the three tech leaders - Nokia, SAP, and Ericsson - also announced restructuring plans. Nokia, the largest European tech investor, presented a headcount reduction of up to 14,000 employees.42 Despite a sharp 21% sales decline last year necessitating immediate action, regulatory constraints in Germany, France, and Finland mean it won't complete the restructuring until 2026. Similarly, SAP, Europe's software leader, announced 8,000 layoffs, 43 provisioning over 18 months of compensation globally, with more than three years required in Europe.”15

Labor laws are hugely important for increasing the leverage for high-performing firms, but also a clear area where increasing the upside increases downside. Given the positive externalities of innovation, it may still leave everyone better off.

Outstanding impact doesn’t require huge inputs. As Marc Andreessen noted:

“Classical Athens, Renaissance Florence, Enlightenment Edinburgh, 1920's Detroit, and 1950's-1970's Silicon Valley … were all tiny populations by our standards”.

Europe has the human capital to do well — it just needs to focus on outliers, not medians. Rules like the Product Liability Directive hurt its ability to create the superstars it needs. There are many things the EU can do to help top start-ups without hurting the left half of the distribution. But if it truly wants to close the innovation gap, Brussels may need to consider options that increase both tails.

The one manufacturing business that has neared software-like growth is that of Elon Musk, who by virtue of his rule-breaking has created a unique environment for testing and experimentation.

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. "Directive (EU) 2024/2853." Official Journal of the European Union, November 18, 2024, 2.

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. "Directive (EU) 2024/2853." Official Journal of the European Union, November 18, 2024, 10.

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. "Directive (EU) 2024/2853." Official Journal of the European Union, November 18, 2024, 8.

Draghi, Mario. "The Future of European Competitiveness: Part A | A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe." European Commission, September 2024, 20.

Draghi, Mario. "The Future of European Competitiveness: Part A | A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe." European Commission, September 2024, 20.

Rosen, Sherwin. "The Economics of Superstars." The American Economic Review 71, no. 5 (December 1981): 845-58.

Rosen, Sherwin. "The Economics of Superstars." The American Economic Review 71, no. 5 (December 1981): 845-58.

Rosen, Sherwin. "Authority, Control, and the Distribution of Earnings." The Bell Journal of Economics 13, no. 2 (Autumn 1982): 311-23.

Arnold, Nathaniel G, Guillaume Claveres, and Jan Frie. 2024. "Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe" IMF Working Papers. July 12, 2024.

Arnold, Nathaniel G, Guillaume Claveres, and Jan Frie. 2024. "Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe" IMF Working Papers. July 12, 2024.

Getz, Daphne, and Itzhak Goldberg. "Best Practices and Lessons Learned in ICT Sector Innovation: A Case Study of Israel." World Development Report Background Paper, World Bank, 2016.

Getz, Daphne, and Itzhak Goldberg. "Best Practices and Lessons Learned in ICT Sector Innovation: A Case Study of Israel." World Development Report Background Paper, World Bank, 2016.

Coatanlem, Yann, and Oliver Coste. "Cost of Failure and Competitiveness in Disruptive Innovation." IEP@BU Policy Brief, September 2024.

Coatanlem, Yann, and Oliver Coste. "Cost of Failure and Competitiveness in Disruptive Innovation." IEP@BU Policy Brief, September 2024.

Pieter I would love to have you as a guest on the Arise News Global Business Report. It airs 10am weekdays UK time. How can I get in touch. Here is one of my last interviews with the World Economic Forum https://youtu.be/Q_Pde-WVm8E?si=qNJYztk4JZnEYbpB

1) "Israel attracted 5.9bn in venture investments in 2022 — three times that of Italy that year."

2) "No European country has more NASDAQ-listed companies than Israel."

Incredible stats given that Israel has 10m people. Comparison: Germany (85m), France (68m), Italy (59m)

As pointed out by the author, an obsessive focus on equity at the expense of nurturing superstars goes against the 80/20 rule. The fact is that not all founders, companies, VCs, and engineers are created equal. Any system that does not reward superstars significantly more is at a huge disadvantage.

Unfortunately, there are deep cultural issues in Europe that will likely continue to hinder its superstars and in turn, growth and outperformance: https://substack.com/@inverteum/note/c-81584888

I hope I am wrong, but with own goal legislation like the Product Liability Directive, I don't think I am.