The Dutch probably live in Europe's best-governed country. Its GDP per capita growth outpaced all other major European economies from 2015-2023. In the EU Commission's 2022 ranking of regional competitiveness, Dutch regions took four of the top five spots. Utrecht (where I grew up) came first. It has the third-highest average income in the EU, after Luxembourg and Ireland.

This makes it all the more surprising that Dutch politics seems to be breaking. The country shares the challenges of its neighbors: an export-driven economy that was reliant to some degree on gas, increasing polarization, and surging house prices.

But it also has a uniquely Dutch problem: quantity targets for nitrogen emissions regulations have meant that since 2019 it has been illegal — or near impossible — to build in much of the country.

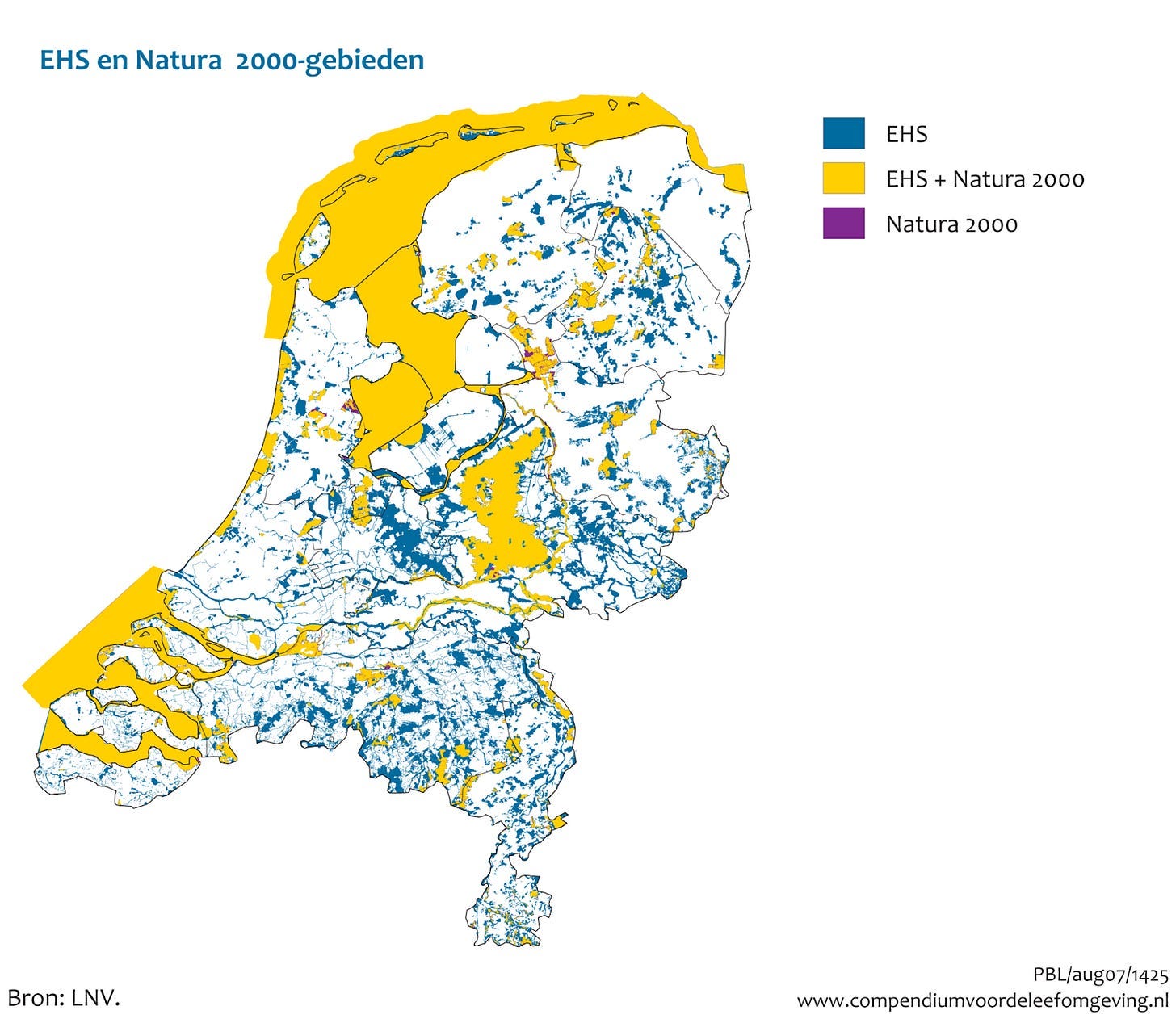

From 1992 onwards, the EU’s Habitats Directive required member states to set aside specific portions of their land as protected nature areas. These areas would form a European network of sanctuaries for endangered species and their habitats. Under the same law, states are legally obliged to protect these areas from actions that lead to ‘the deterioration of natural habitats and the habitats of species’. In particular, subsequent Dutch law backed up by European courts established thresholds for depositions of nitrogen compounds, which make soil more acidic, and cause certain plants to overwhelm others, harming natural diversity.

The key is that these rules target quantity, not prices. This is quite an important point: quantity targets (e.g., setting a cap on the emissions of a certain particle) mean that you have to hit the target no matter what the cost. In the case of European nature preserves, nitrogen must be below certain thresholds regardless of the cost of abatement.

The problem for the Netherlands is immediately clear. The country has high density, little nature, and a very intensive agricultural industry — it is the second-largest exporter of agricultural products in the world by value. To reach its targets for nature preserves, the state snipped them up and spread them throughout the country. Due to their proximity to large and intensive farming and industrial activities, nitrogen compound legal thresholds have been significantly breached across the country.

To avoid intervening, the Dutch government relied on rules (PAS - Programma Aanpak Stikstof) to defer emission reductions through complex temporal averaging mechanisms. In May 2019, following guidance from the European Court of Justice, the country's highest court ruled that this accounting violated the Habitats Directive. Immediately after the ruling, a majority of new construction projects were frozen and the government cut highway speed limits by 30 km/h to reduce emissions. Subsequently, the government announced a 2% of GDP program to buy out and close farms. It also developed new targets for emissions and new ways of allocating licenses.

In January 2025, the court ruled these new methods illegal too. Effectively, most new construction projects are at risk of becoming unlawful again.

The country is at an impasse. (Forcibly) buying out farmers is politically unpopular — the current coalition was elected on the premise of supporting them. Halting construction is suicide in a country facing one of the worst housing shortages in Europe. The expected bill for this latest court case is in the range of 1 to 1.5% of GDP.

The mistake was the one made at the start. When one is uncertain about the likely outcome, the right choice between price and quantities in environmental regulation depends on the relative slope of the cost of abatement versus that of environmental damages, as Weitzman (1974) demonstrated.

When the potential damage is very high — say you have the possibility of a catastrophic event once a threshold is breached — quantity controls become preferable as they prevent you from overemitting, even if there may be some inefficiency.

When the potential cost of regulating is very high, price instruments like taxes allow for efficient adaptation. Under a tax regime, firms can calibrate their abatement efforts based on their costs, avoiding the rigidity that results from a predetermined quantity allocation.

In the case of nitrogen, quantity targets mean that construction has to be stopped once the threshold is breached, no matter the damage. A priori, if you'd asked Dutch politicians whether they would have signed on to having this trade-off, I suspect they would have said no, but because they chose to target quantities over prices, this is the outcome we get.

While the nitrogen crisis is unique to the Netherlands, quantity targeting has been rife across the continent. The ICE ban (establishes that new light vehicles must be zero-carbon by 2035), the Effort Sharing Regulation (sets nationwide targets for carbon emissions), the Sustainable Fuel Mandates for Aviation and Shipping (force the respective industries to use new low-emissions fuels), the Nature Restoration framework (sets targets for improving biodiversity) and a host of other rules all operate on these principles. As thresholds are breached, abatement will be imposed no matter the costs, even if the actual benefit seems quite limited in comparison.

To be clear, this is not a case for less environmental regulation. The objectives in question for these rules may be desirable. Instead, it's an illustration of Weitzman's basic point: when the possible costs of abatement get very steep/non-linear, it is important to choose prices rather than quantity targets. The Netherlands' problems with nitrogen is a warning of how ugly the trade-offs can become.

Coda: why can’t they solve it?

Whenever you tell the story to foreigners, it always leads to quite a lot of surprise — if a country is so well-run, why can't the government simply either hit the targets or change the rules?

The basic problem is institutional. Dutch voters have indicated that they prefer to have houses and farmers over biodiversity. But the view of the state is that they cannot be changed.

The Netherlands is famous for the polder model, its consensus-driven political system whereby critical issues are hashed out based on lengthy negotiations between the state, industry groups, consumers and other stakeholders. The EU requires even greater levels of consensus, with major decisions requiring unanimity or the assent of a majority of member states. Both systems make rapid error correction — even in a case like nitrogen where the costs are extremely high — very hard.

Changing the Habitats Directive would require the majority assent of other EU members. Non-compliance would be illegal and (possibly) lead to sanctions from the ECJ. Changing the Natura 2000 areas requires recognition from the Commission that ecological criteria have been met. For the Commission to give a nitrogen reprieve to the Dutch would be to worsen an EU regime where one country gets special treatment, which the Commission considers unacceptable.

The other issue appears to be cultural. British campaigner Jeremy Driver coined the term ‘Cheems Mindset’ to describe ‘'the reflexive belief that barriers to policy outcomes are natural laws that we should not waste our time considering how to overcome'. In the case of nitrogen emissions, the starting point for Dutch politics is that the laws 'are what they are', and the state and its citizens are stuck with them.

There would seem to be lots of possible outcomes that satisfy targets and social objectives — I would prefer the Netherlands to be a country with abundant housing and don't believe its comparative advantage necessarily is high-intensity farming — but as of right now, no one in Dutch politics is articulating a viable path to get there.

Unfortunately, just like quantity targeting, these aggravating factors are widely present elsewhere in Europe.

So far the evidence is that the EU is slower still at error-correction than its member states. The EU AI Act is probably going to noticeably hurt the roll-out of AI in Europe in single-digit months, but there is no public path to fixing it. Reliance on unanimity to change treaties and qualified majorities of member states for regulations means that rapid change is near impossible.

Nor does ‘Cheems mindset’ seem to be a uniquely Dutch trait. Across Europe, high energy prices are currently taken as a fact of life due to Europe’s geographic endowment, not an outcome of policies we can change. GDPR is treated as fixed and unchanging rather than an obstacle that can be adjusted. On immigration, policy changes 'cannot be made' due to ECHR. The nuclear shutdown cannot be remedied because it cannot be done.

This will get worse rather than better: as the world gets more complex, the costs of institutions that can't fix mistakes and a culture that thinks bad policy outcomes are a fact of life are going up. Quantity targets and the inability to error-correct have already led to paralysis in Europe's best-governed country. While the case is country-specific, the factors that led to it are present continent-wide.

Some more context:

In the Netherlands there is no threshold value for nitrogen deposition for permitting purposes. So that even the most minor sources of nitrogen (like dance festivals, militairy training grounds, and house building) are regulated. This leads to ridiculous ecological bureaucracy where you have to show that traffic from your dance festival does not produce deposition on Natura 2000 areas. Festivals have been banned because of this (I speak from experience).

In Germany there's a much higher threshold value for permitting purposes, which has been ruled legal by their highest administrative court. The Bundesverfassingsgerecht says it's not a matter of 'interpretation of EU law' (in which case you would have to ask the ECJ if your interpretation is correct), but of 'application of EU law' (in which case you don't). Whether they are right is the question (they might not be), but there's now no way they are ever going to to change their threshold value.

So you now have two neighbouring countries who interpret the same EU law in a completely different way (with far reaching consequences). Great!

A problem with the nitrogen regime is that it regulates the consequences (in the Netherlands: deposition of nitrogen on Natura 2000 areas that exceeds the critical load), not the sources (farmers, industry, road traffic).

To draw an analogy: it would be like a system where we regulate greenhouse gas emissions by saying, we have a dyke, and you have to show that your activities don't lead to higher dykes. It's not the way to do it.

To be fair: nitrogen has more local consequences. But in the Netherlands you still have about 1/3 of all deposition which is from foreign sources. It's been shown that even if you were to delete all meat and dairy production in the Netherlands, you would still end up with Natura 2000 areas which exceed the critical load, because of foreign nitrogen. And when you draw a circle of 25 km (the threshold for permitting purposes) of all Natura 2000 areas that exceed critical load just from foreign sources it basically covers the entire Netherlands.

It would be preferable to split ammonia emissions (from agriculture) from nitrogen oxide emissions (from construction, industry, transport). The second are going to fall anyway if you stop burning fossil fuels and electrify. For ammonia it would be good to have some type of emission trading. But this is complicated because of more local consequences of ammonia emissions (there's exponential decay in nitrogen depositions, so that sources close to areas are responsible for more deposition).

Crazy! And an excellent post. I take two issues. First, with time: we should be more careful with policymaking that constrains future generations' policy options. One generation imposing their will on voters ten-twenty years down the line is not exactly democratic. Second, with place: you note correctly that the Netherlands are constrained by the EU's yesteryear decisions. To the extent that the Dutch PM didn't veto those rules in the European council, Dutch voters have themselves to blame (for voting in the PM). To the extent that other countries' supermajorities imposed the regulation on the Netherlands, Dutch voters have noone to blame. They can only resent the other countries (and exceedingly the courts) for imposing their policy preferences on them. That's not a good recipe for European friendship or trust in institutions. Now, there have been hopes that the European parliament, the Spitzenkandidatmodel and what not could overcome the perceived lack of legitimacy. But to date this hasn't quite worked. Few could list the names of European parliamentarians, whereas national MPs are household names. If you draw these two issues to its logical conclusion, two principles of institutional design might receive a rethink: First, we may have gone too far in relaxing unanimity (as it existed before the Lisbon treaty) in the European Council. (Considering that the European Council enjoys greater legitimacy as its members contest fierce elections and are therefore well-known to the voting public.) Second, as you note, many measures that pass are not well-crafted; others unduly constrain future generations. So how about drafting legislation that comes with an expiry date?