Europe's climate consensus is in trouble. Abrupt mandates that burden ordinary citizens — from forced heating system replacements to bans on affordable rental housing — are triggering a backlash that threatens to deliver our continent to the extreme right. Downstream effects — high energy costs, lower growth — breed resentment.

The risk that Europeans reject climate policies increases with Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement on his first day as US President and his declared intention to “drill, baby, drill”. After all, climate is a global public good, and free-riding has clear benefits to the free-rider—at high costs to the planet.

And yet, climate change remains a real and growing threat — 2024 again recorded the highest average global surface temperature on record. Our planet is clearly warming dangerously. What would be a new climate consensus that can keep democratic support while meeting our climate goals? Here are some potential principles:

All climate policy should be subject to explicit cost-benefit analysis. Each climate measure cannot become an end in itself. The final objective of European policy should be the flourishing of its citizens; stopping climate change is an important step, but not the only one. Nobel prize-winning economist William Nordhaus first introduced a cost-benefit approach to climate change. His Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy model explicitly trades off climate benefits of reducing carbon emissions against costs. He proposed a gradual reduction in emissions using carbon pricing, and argued that “rigid emissions or climate-stabilization approaches would impose significant net costs.” Arbitrary, voluntaristic deadlines and targets with no assessment of costs and tradeoffs — like the EU 2035 ban on internal combustion engines or the legally set 2050 decarbonization goal — need to be dropped. The argument that they provide certainty is misleading— unrealistic deadlines are not credible.

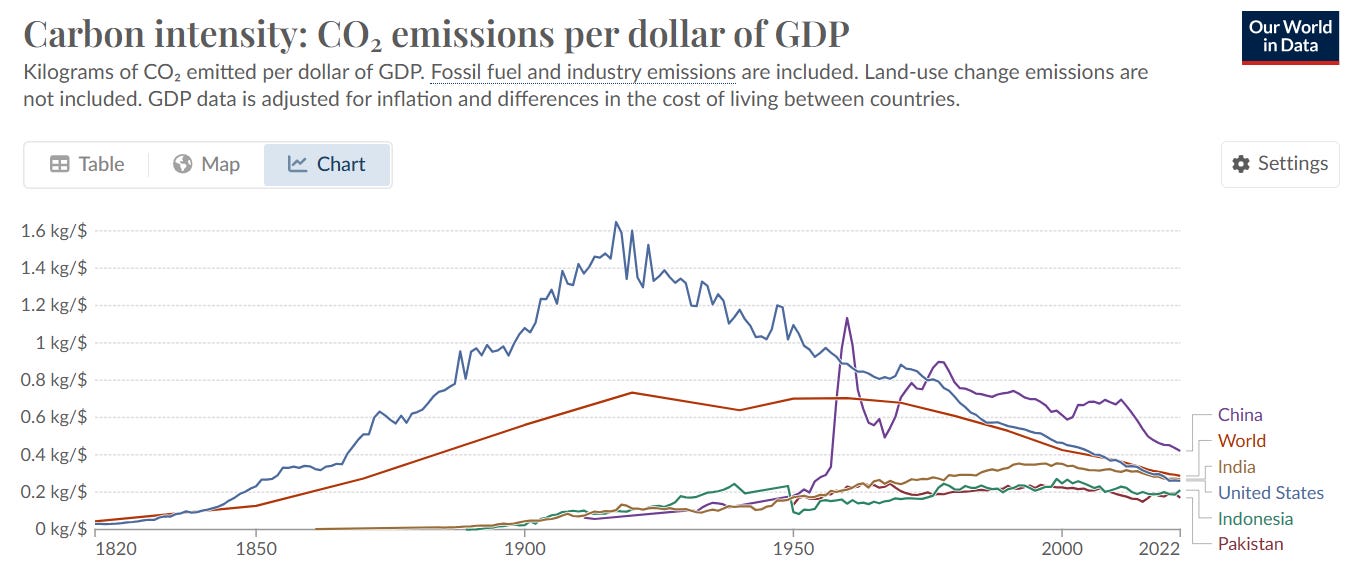

Growth is good. Increasing growth rates is one of the most important things we can do for the climate. A larger GDP not only improves living standards but also provides the resources needed to fund the green transition. Our young people deserve better than a future of planned stagnation, and developing countries cannot be expected to freeze at current levels. In fact, as Hannah Ritchie demonstrates in her book Not the End of the World (2024), wealthy nations have reduced air and water pollution while growing their economies. As we grow, producing a dollar of GDP requires, over time, fewer and fewer CO2 emissions.

Carbon intensity of C02. Source: Our World in Data Use incentives, not mandates. Consider France's dirigiste approach to building energy efficiency. Starting January 1st, 2025, any property with the lowest energy rating (G) has been banned from the rental market entirely, with bans extending to F-rated properties by 2028 and E-rated properties by 2034. France has 5 million F and G-rated properties, many providing affordable housing in city centers. Rather than spend tens of thousands of euros in renovations, many landlords will pull the buildings from the rental market, aggravating the housing crisis. The political cost of such heavy-handed moves creates anger and undermines support for climate efforts. Nor can politicians, if they are to succeed, rely on guilt-tripping citizens, including by demonizing air travel (just 2.5% of global emissions) or personal consumption choices. Better choices will follow from incentives, not mandates or guilt.

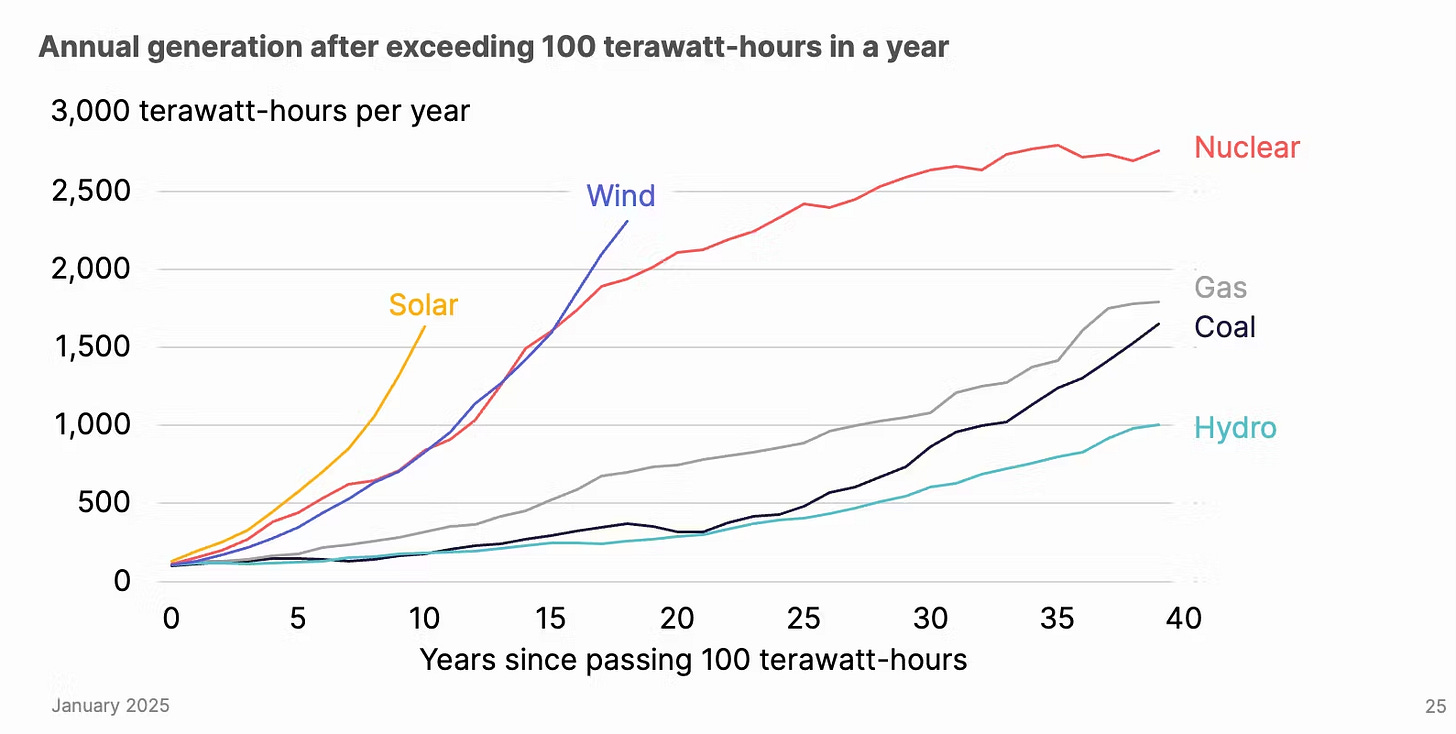

Avoid catastrophism. The rhetoric of emergency backfires: it alienates people instead of mobilizing them, and when voters hear disaster is inevitable, they rationally question why they should sacrifice at all. It is also not true: current policies put us on track for 2.7°C warming by 2100, not the apocalyptic 4-5°C scenarios of the 2000s, thanks to the slowdown of coal and expansion of renewables. Our language must recognize climate change as a serious but manageable problem — one we're already making progress on. Rapid technological improvements in batteries, wind, and solar — with costs decreasing exponentially — suggest we could do even better. The decrease of global emissions intensity by 25% since 2000 has shown global progress and emissions reduction can coexist.

Trade-offs are real. In March 2023, Olaf Scholz promised a new German economic miracle declaring that green investment would help “Germany achieve growth rates last seen in the 1950s and 60s.” This promise was always going to be hollow: the postwar economic miracle saw investment create new productive capacity; today's green investment largely replaces existing capacity — shutting down coal plants to build wind farms, swapping gas boilers for heat pumps. While necessary for climate reasons, replacing our capital stock maintains rather than expands our productive capacity. We shouldn't pretend it's an economic “stimulus” — this misleads voters and undermines trust in climate policy.

No technology can be taboo. Carbon removal, nuclear and geoengineering should be evaluated based on their marginal cost per ton removed and their impact on growth, rather than on dogma. Opposition to all of these, framed as a test of virtue (if you care, you must want to make sacrifices), is misguided. The truth is, if climate is an important problem, all solutions must be considered. Europe needs to prepare for a world where other nations start using geoengineering unilaterally, rather than excluding it from forecasting.

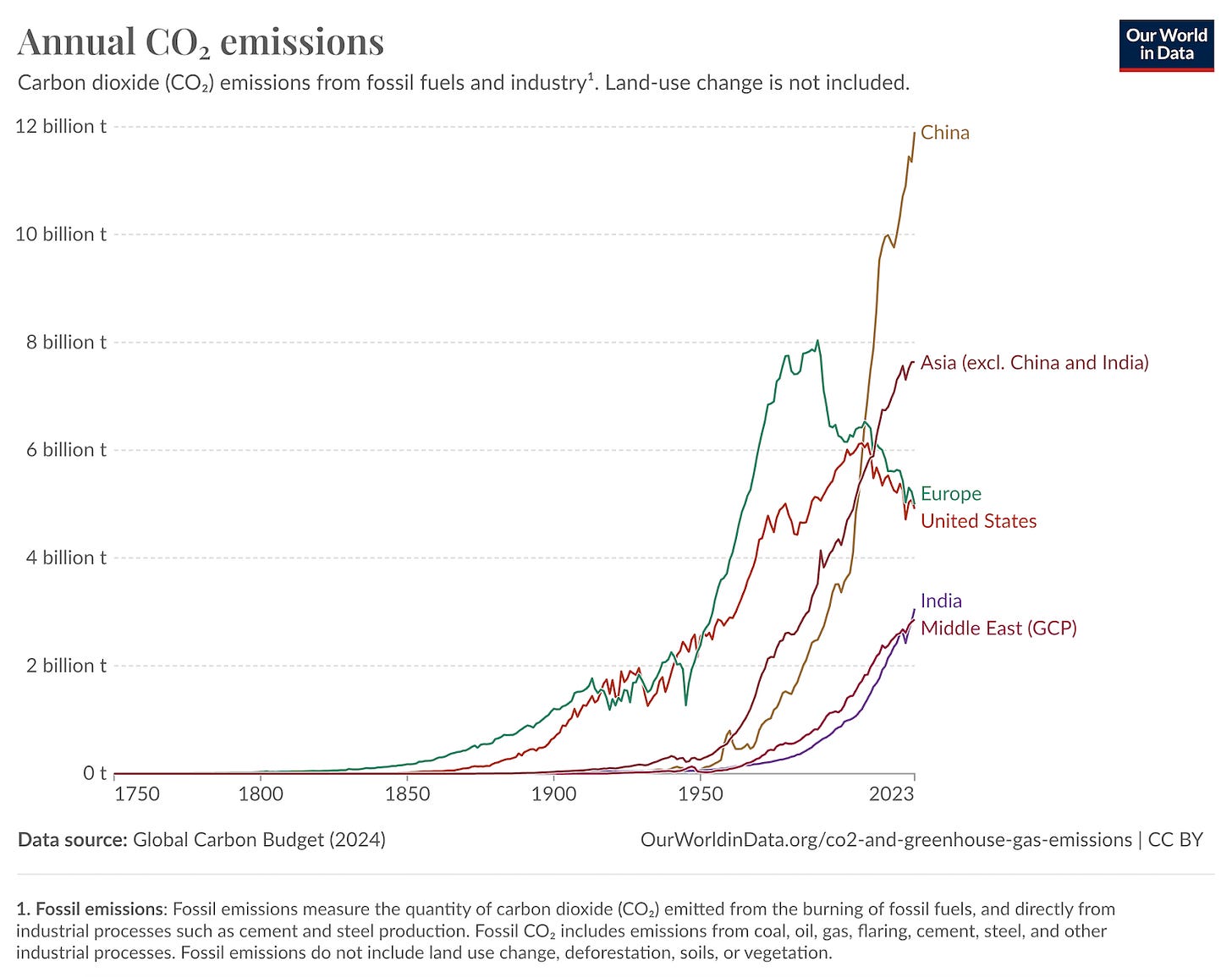

Europe cannot do it alone. The EU produces roughly 6% of global emissions. It produces 33% less carbon per capita than China. Unilateral action does not greatly improve the climate, but — if it hurts growth — weakens Europe relative to other powers with worse intentions and targets. If we accept that domestic growth and support for climate are good, destroying our industry with unilateral measures is bad for the globe long-term. If climate politics is to be both successful, and legitimate in the eyes of the voters, Europe must focus on suppressing emissions globally rather than locally. Our climate policies must provide incentives to other countries to join our efforts.

Building must be cheap. The fight against climate change is currently being slowed by local groups weaponizing (biodiversity) rules to block essential green infrastructure. Across Europe, transmission lines, rail projects, and wind farms are stalled. While both climate and biodiversity matter, we should not confuse the two. Too much European investment is wasted due to long delays caused by procedural manoeuvring. A possible solution is to compensate elsewhere for local biodiversity loss where the building is necessary-- we cannot compensate for climate failure. Efficiency and speed are as important as scale — lowering the cost of building is a key part of that.

Focus on public goods, not industrial policy. The state’s main role here should be providing essential public infrastructure and research - not picking industry winners or micromanaging the private sector's green transition. Industrial policy needs clear objectives (see our discussion in this blog on the conditions for its success) and it is not the right policy to achieve climate goals. Governments should focus on genuine public goods and on solving coordination problems: building charging networks, funding basic research in clean energy and ensuring transmission infrastructure keeps pace with renewable deployment.

Climate policy should not be a vehicle for other agendas, including environmental or social objectives. Using it to push unrelated programs builds resentment and dilutes climate action itself. It polarizes voters who might otherwise support a straightforward emissions policy.

So what do these principles look like in practice? Europe should light a bonfire of climate regulations and leave in place only three.

First, we must expand the EU Emissions Trading System. Critics initially argued that the system would fail to reduce emissions significantly or would harm economic growth. Yet it has proven remarkably effective: sectors covered by the ETS have reduced emissions by half since 2005, while maintaining economic growth. The system's flexibility allows emissions cuts to happen where they're most efficient, avoiding the rigid mandates that have triggered such fierce opposition.

The logic of the ETS is beautifully simple: every ton of emissions has priced-in the cost to the planet — whether it comes from a private jet, a steel factory, or a gas heater. There is no need for moral hectoring about which emissions are 'virtuous’ or ‘wasteful’. A mill producing steel and a couple flying to Ibiza both pay the cost of their carbon impact. People and businesses are free to choose how they adjust – some will cut emissions where it's cheap to do so, others will pay more where alternatives are costly. What matters is that it ensures resources flow to where emission cuts are most efficient. But maintaining public support requires that carbon revenues go back to citizens (as they do in British Columbia), not fill state coffers (as we do in Europe). Carbon pricing must remain a tool for changing behavior, not raising revenue — this is how one avoids hitting poorer households disproportionally.

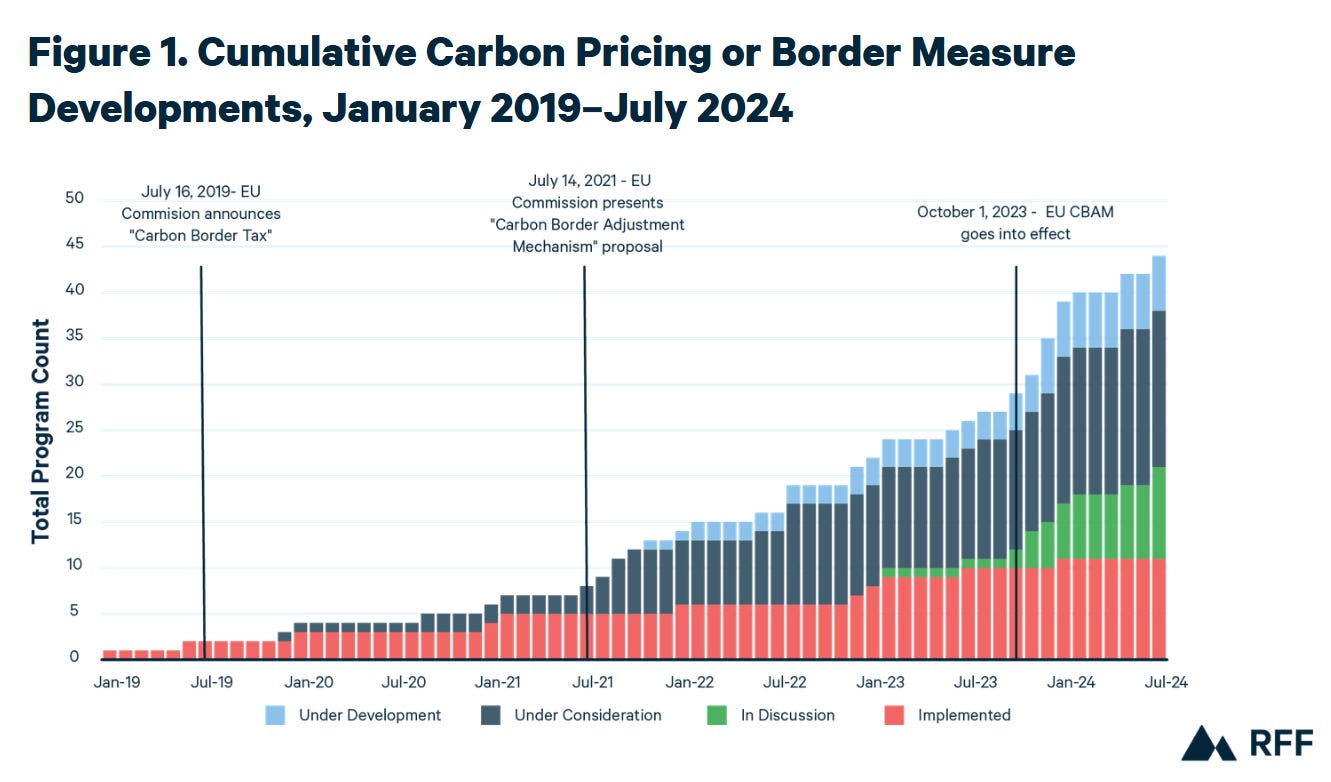

Second, implement a workable, broad, Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is set to start charging importers in 2026. It puts a price on the carbon content of imports, creating powerful incentives for other countries to adopt carbon pricing. When countries export energy-intensive products to Europe, they can convert European tariff revenue into domestic revenue by adopting their own carbon prices. A recent paper by Clausing, Elkerbout, Nehrkorn, and Wolfram (2024) suggests this is working: since CBAM's announcement, the number of carbon pricing initiatives worldwide has grown from 57 to 75, now covering about a quarter of global emissions. Even China is responding, considering adding steel, cement, and aluminum to its emissions trading system ahead of CBAM's implementation, while the United Kingdom has followed Europe's lead, announcing its own CBAM for 2027.

Source: Clausing, Elkerbout, Nehrkorn, and Wolfram (2024).

Third, invest in public goods. The state does have a role. Not making mandates and imposing arbitrary rules, but investing in the critical charging infrastructure and in research and development for clean energy. Subsidies here are appropriate — ETS does not by itself provide enough investment incentives, given the coordination and knowledge appropriation externalities.

Europeans can be proud of our leadership in the global fight against climate change. But maintaining democratic support for meeting our Paris targets requires that we modify our approach. Our emphasis on trade-offs over purity, and growth over austerity, will make many climate activists uncomfortable. Yet as French king Henry IV said when converting to Catholicism in 1593 to end the wars of religion, ‘Paris is well worth a mass.’ The alternative isn't some green utopia — it is a weaker, poorer Europe governed by Le Pen and AfD. One can imagine what that would mean for climate action, or for Europe itself.

References:

Clausing, Kimberly, Milan Elkerbout, Katarina Nehrkorn, and Catherine Wolfram. "How Carbon Border Adjustments Might Drive Global Climate Policy Momentum." Resources for the Future, Report (2024): 24-20.

Nordhaus, William D. "An optimal transition path for controlling greenhouse gases." Science 258, no. 5086 (1992): 1315-1319.

Ritchie, Hannah. Not the End of the World: How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet. Random House, 2024.

I really appreciate yourdiscussion of European economic policy. It is always very factual and specific and never generalmor vague.

We may quarrel over the details, but the return to the Vital Centre of European political life is essential. Reason, facts, balance, and good sense I now needed more than ever. Let's keep thinking it's an old European tradition in need of reviving. It's called enlightenment.