In a 2015 profile, Demis Hassabis, CEO of DeepMind, refers in passing to a competitor: the EU Human Brain Project. DeepMind has gone on to become a leader in AI, and Hassabis a Nobel Laureate in Chemistry for his work on protein folding. Meanwhile, the Human Brain Project is widely regarded as a failure — one of a number of stillborn European efforts to lead in technology. The divergence of the two underlines a deeper point: the EU's innovation challenges are not due to a lack of public spending on R&D.

The Human Brain Project

The Human Brain Project, launched in 2013, was one of the European Commission's ‘innovation flagships’. It aimed to simulate a human brain at the cellular level within ten years. The initiative was initially allocated 600 million euros in funding from 2013 through 2020 under the Horizon 2020 scheme. It was part of a familiar-sounding effort to increase "European competitiveness" in "future and emerging technologies."

By 2023, the EU had in fact not achieved its goal of simulating a human brain. The Human Brain Project is widely seen as a failure. Throughout its duration, the project went through many leadership changes and repeated restructurings. A journalist reporting on the project for the Atlantic in 2019 wrote: "the people I contacted struggled to name a major contribution that the HBP has made in the past decade."

Part of the problems faced by the Human Brain Project stemmed from the choice of technology pathway. Whole brain emulation, where one tries to create an artificial intelligence by mimicking each individual neuron in a brain. This was an idea that generated excitement in the early 2010s but it has been largely left behind by advances in language models and approaches that mimic the brain at a systems level.

These problems were clear early on. Geoffrey Hinton, the recent Nobel Laureate in Physics said about the plans for the HBP in 2012, "The real problem with that project is they have no clue how to get a large system like that to learn."

The Human Brain Project was not alone. There were other innovation flagships and priorities in Horizon 2020.

The Quantum flagship aimed to establish European leadership in quantum computing. That field is now mostly contested by China and the United States.

The Commission’s 2013 Space funding initiative was meant to ensure “independent access to space and the development of competitive space technologies”. The phasing out of the rocket Ariane 5 and issues with Ariane 6 means Europe has no reliable independent access to space.

Horizon 2020 was funded at 77 billion euros. Its successor, Horizon Europe, runs from 2021 to 2027 and will receive 95.5 billion euros.

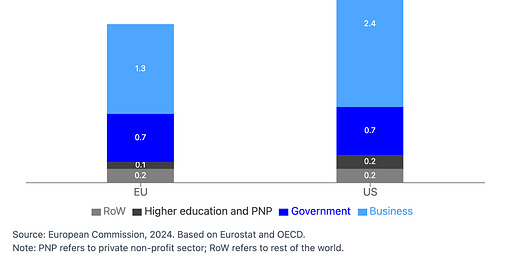

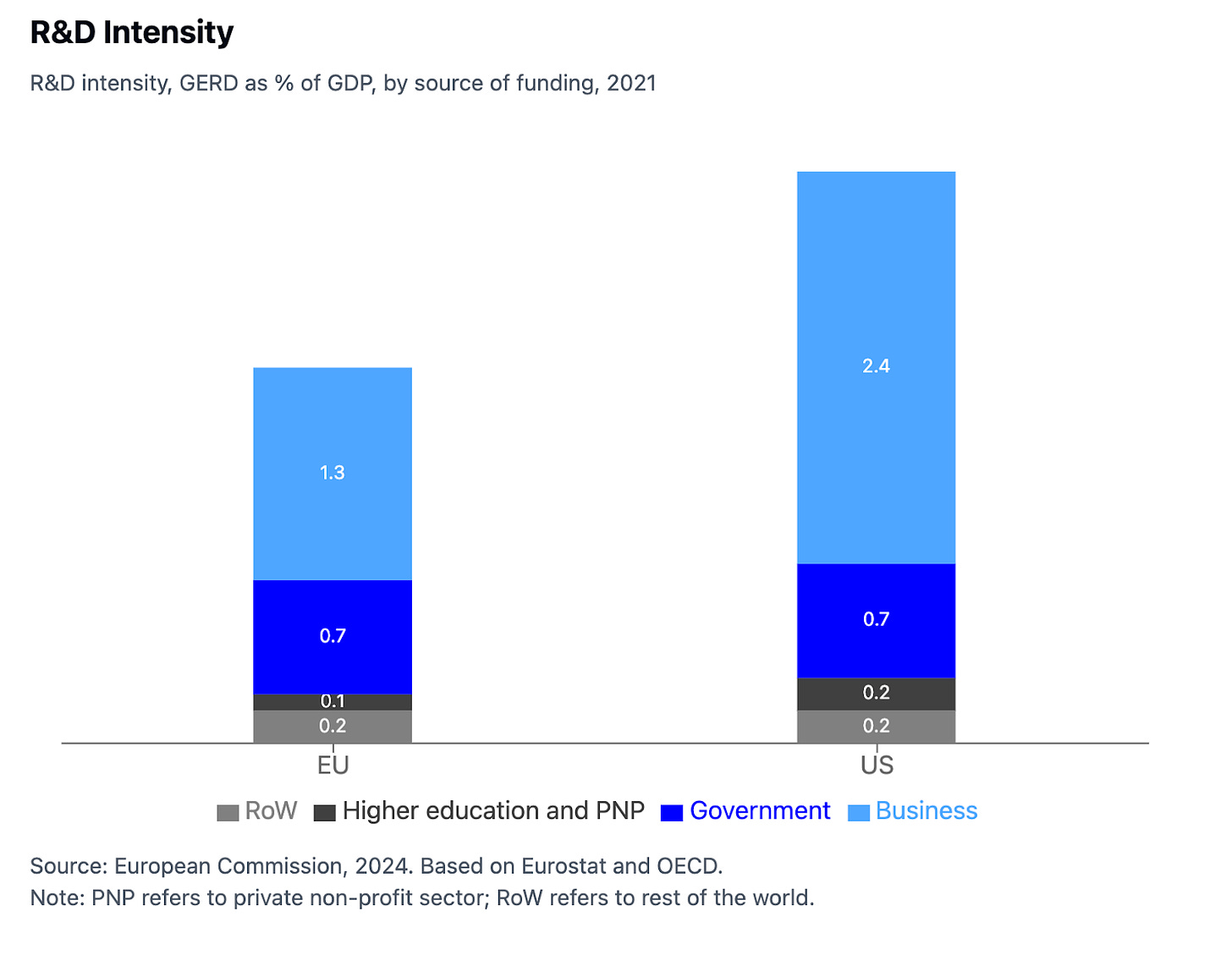

These are symptoms of a broader point: unlike what is commonly believed, Europe is not lagging in government investment in science. As a share of GDP, Europe spends roughly 0.74% on public sector R&D, compared to the United States' 0.69%. Total governmental R&D spending in 2021 is roughly 131 billion in the US and 108 billion in the EU.

The actual R&D gap is in private sector spending, where Europe spends 1.3% of GDP compared to the United States' 2.4%. That gap is good for 341 billion in R&D spending in 2021.

Indeed, a common misconception among some economists and policy makers is that the United States leads in innovation due to the work done by publicly funded researchers, particularly by the Defense Department. In reality, Defense Department R&D represents less than 10% of total R&D in the U.S. Many of the great innovations to come out of the Pentagon are now decades old. The areas where Europe is now most clearly falling behind are almost wholly being driven by the private sector: AI, space, EVs.

More than half of the private sector spending gap can be attributed to the top 10 U.S. tech companies. The top 5 U.S. tech companies alone (Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Apple, and Microsoft) collectively spent around $202 billion on R&D in 2022. The data shows the area where Europe falls behind is private, not public, funding.

DeepMind reflects this story. Their initial funding round was largely backed by American, not European investors, including Peter Thiel, Elon Musk and a number of big name venture funds. While the EU Human Brain Project was being launched, DeepMind was bought by Google for 400 million in 2014. Its AI research is now funded by the firm on the order of billions per year.

What is to be done?

Both the issue of getting more private sector R&D funding, as well as better structuring public R&D funding deserve deeper pieces of their own, but we may preview a number of issues.

First, a lot of the gap in R&D spending can be explained by compositional effects. U.S. technology firms are simply in much more R&D-intensive sectors than the areas Europe excels in. A nice fact illustrates this: Twenty years ago, the United States top three firms for R&D were Ford, Pfizer and GM, while Europe’s were Mercedes-Benz, Siemens and Volkswagen. Today, the top three firms in the United States for R&D spending are Amazon, Alphabet and Meta Europe’s are Volkwagen, Mercedes and Bosch.

Research by Fuest et al. (2024) suggests that the differences in industry composition are responsible for about 60% of the R&D spending gap. If the EU's economy were structured similarly to that of the US, private sector R&D spending in the EU would reach 2.2% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) — much closer to the United States’ 2.4% Flourishing private sector innovation begets more innovation.

Second, part of the gap in outcomes can be explained by how public monies are actually spent. It is no wonder that Draghi wishes to pursue a European DARPA. Such an effort is much needed to avoid the boondoggles that have been in certain past EU innovation projects.

Take Horizon Europe. Resources are spread thinly across numerous fields. Its governance is excessively complex, involving Commission departments, Member States, and the European Parliament, without a clear mechanism to align EU-wide and national priorities.

Accessing its funding is notoriously difficult, especially for newcomers. The program suffers from bad oversubscription, with 70% of high-quality proposals failing to secure funding. The program's rules for submitting proposals and managing projects are complex, creating unnecessary barriers for less-established players.

Most concerning is lack of disruption. The European Innovation Council's (EIC) Pathfinder instrument, designed to fund entirely new technologies, is underfunded compared to its counterparts. With a budget of only 250 million euros for 2024, it is small in comparison to the resources available to US agencies like DARPA (4.1 billion USD in 2023), ARPA-H (1.5 billion USD), and ARPA-E (0.5 billion USD).

The governance of these programs compounds the problem. Unlike the ARPAs, EIC is primarily led by officials rather than scientists and experts. Bureaucratic leadership creates an environment that is poorly suited to nurturing rapid, disruptive innovation.

Third, some forms of private sector spending have a much higher impact than others. In total, seed, early and late stage venture spending in the U.S. is no more than $170 billion per year. Its impacts on innovation are enormous. Almost every successful private and technology enterprise has received venture funding at some point or another. But in Europe, VC is just 0.05% of GDP compared to 0.32% across the Atlantic. Reforms to boost venture capital activity, particularly to the regulatory hurdles which prevent institutional investors from spending more, are urgently needed.

Fortunately according to Arnold et al (2024) there are a number of low-hanging fruits. Solvency II rules governing insurers' investments treat VC as riskier than it should. At a national level, pension fund regulations significantly restrict their exposure to VC. The AIFMD rules that govern funds larger than $500 million restrict participation to accredited ‘professional investors’ — meaning that oftentimes even sector experts cannot participate in venture investing.

Conclusion

All three approaches pose challenges in their own way. Changing the composition of the tech sector presumes solving the problem more R&D spending is meant to solve. Problems with EU spending institutions and focuses are often the result of political conflicts and clashing national incentives, not a lack of knowledge. Issues with private investment and venture capital stem from deeper cultural differences and risk aversion, as well as easier-to-remove regulatory hurdles. Yet tackling all three will be crucial.

The case of DeepMind offers a hopeful lesson. It continues to be headquartered and led from London. Talent plays a major role in that. As Hassabis explained in a 2015 interview: "If you've got a PhD in physics from Cambridge and want to do some world-changing technology, there aren't that many options here — in Silicon Valley there are thousands. And if you're focusing on a long-term goal, the Valley can be a bubble —- people trying to create the next Snapchat every five minutes. There can be a lot of noise in the system."

The correct inputs are there. A venture capitalist I spoke to recently said that all investments he had made in Europe had been failures, but all Europeans he had funded had been disproportionately successful. Europe, not the Europeans, is the problem. Allowing large amounts of private resources to flow to the right people and ideas is the key first step towards mitigating that.

References

Arnold, Nathaniel G, Guillaume Claveres, and Jan Frie. 2024. "Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe" IMF Working Papers. July 12, 2024.

Brean, Joseph. 2012. "Build a better brain? Scientists keep trying, but many agree that it's all but impossible" National Post. https://nationalpost.com/news/build-a-better-brain-scientists-keep-trying-but-many-agree-that-its-all-but-impossible.

Draghi, Mario. 2024b. "EU Competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations" EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

European Commission. "EU-funded space R&I in previous EU Framework programmes for Research and Innovation" https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-space/research-development-and-innovation/eu-funded-space-ri-previous-eu-framework-programmes-research-and-innovation_en

Fuest, Clemens, Daniel Gros, Philipp-Leo Mengel, Giorgio Presidente, and Jean Tirole. 2024. "EU Innovation Policy: How to Escape the Middle Technology Trap".

Naddaf, Miryam. 2023. "Europe spent €600 million to recreate the human brain in a computer. How did it go?" Nature. https://nature.com/articles/d41586-023-02600-x

Rowan, David. 2015. "DeepMind: inside Google's super-brain" WIRED. https://wired.com/story/deepmind/

Yong, Ed. 2019. "The Human Brain Project Hasn't Lived Up to Its Promise" The Atlantic. https://theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/07/ten-years-human-brain-project-simulation-markram-ted-talk/594493/

Switzerland has been kicked out of Horizon some years ago and had to create it's own program. What I hear from people who participated in both is they are happy about the change because the Swiss program requires much less requirements and paperwork.