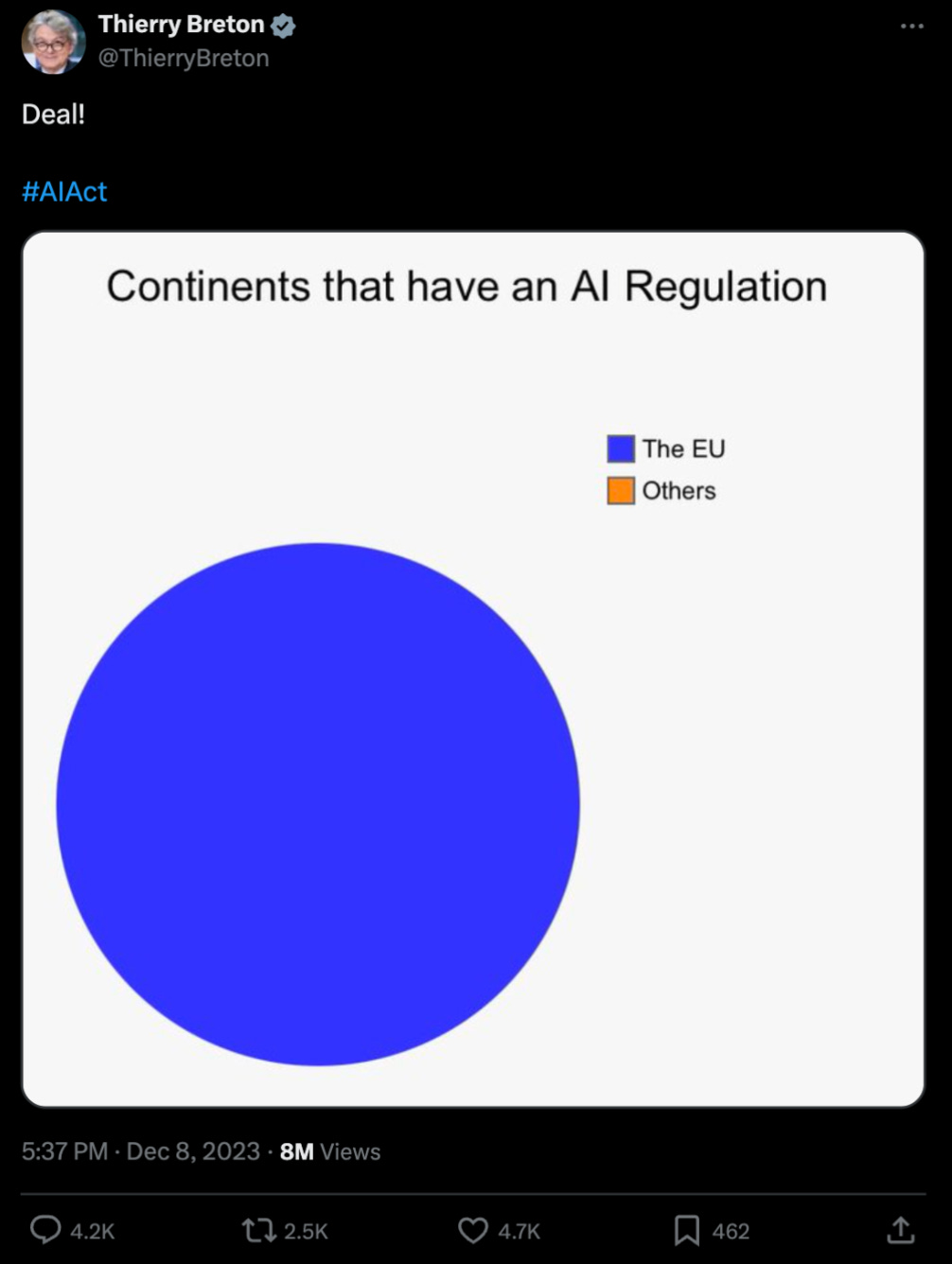

Personal news: I have received an Emergent Ventures grant to work full time on this substack for the next few months. We hope to contribute to a movement for growth, progress and innovation in Europe. If you’d like to get in touch please message pieter [dot] garicano [at] gmail [dot] com. You can follow me on twitter here.

An AI bank teller needs two humans to monitor it. A model safely released months ago is a systemic risk. A start-up trying to build an AI tutor must produce impact assessments, certificates, risk management systems, lifelong monitoring, undergo auditing and more. Governing this will be at least 50 different authorities. Welcome to the EU AI Act.

The Initial Approach

Originally, the way the AI Act was supposed to work is by regulating outcomes rather than capabilities. It places AI models into risk categories based on their uses — unacceptable, high, limited and minimal risk — and imposes regulations for each of those categories.

Unacceptable risk models are prohibited in all cases — this includes systems that do social scoring, emotion recognition in the workplace and real time biometric identification in public — while limited and minimal risk AI — such as data categorisation and basic chatbots — are relatively lightly regulated.1

Many important AI uses, however, are treated as ‘high risk’. These are:

Systems that are used in sectors like education, employment, law enforcement, recruiting, and essential public services2

Systems used in certain kinds of products, including machinery, toys, lifts, medical devices, and vehicles.3

Once a system has been categorized as ‘high risk’, it faces extreme restrictions. Imagine you have a start-up and have built an AI teacher — an obvious and good AI use case. Before you may release it in the EU you must do the following:

Build a comprehensive ‘risk management system’4

Ensure the system is trained on data that has ‘the appropriate statistical properties’5

Draw up extensive technical documentation6

Create an ‘automatic recording of events across the systems lifetime’7

Build a system so a deployer can ‘interpret a system’s output’8

Build in functions for ‘human oversight’ and a ‘stop button’9

Build a cybersecurity system10

Build a ‘quality management system’ that includes ‘the setting-up, implementation and maintenance of a post-market monitoring system’11

Keep all the above for the next 10 years12

Appoint an ‘authorized representative which is established in the Union’13

Undergo a ‘conformity assessment’ verifying that you have done the above with a designated authority and receive a certificate14

Undergo a fundamental rights impact assessment and submit that to the Market Surveillance Authority15

Draw up an EU Declaration of Conformity16

Register in an EU database17

If you get any of that wrong, you may be fined up to the higher of 15 million euros or 3% of total revenue.18

Some of the rules are still more onerous. Take the case of installing an AI bank teller— a ‘high-risk’ case if it uses real-time biometric info. Under the Act:

“No action or decision may be taken by the deployer on the basis of the identification resulting from the system unless this has been separately verified and confirmed by at least two natural persons”19

That is to say the AI bank teller must be supervised not by one but by two humans! This is after building extensive risk management, quality management and cybersecurity systems, preparing impact assessments, explicitly logging all training data and providing oversight and training for the firm actually deploying the AI.

What about LLMS?

So far, the cases we have discussed are the ones the drafters were originally considering under their ‘risk-based’ approach. The release of ChatGPT caught them by surprise, so they included a new category: ‘General Purpose AI models’ which are regulated not on use, but on capabilities:

“A general-purpose AI model’ means an AI model, including where such an AI model is trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications.”20

This definition includes all the LLMs people are interacting with every day. Such a general purpose model becomes a ‘systemic risk’ if it has been trained using 10^25 floating point operations — a threshold already reached by GPT-4, Gemini, and LLAMA 3.1 — or if the European Commission chooses to designate the models as systemic risks based on its capabilities, even if it falls below the computational threshold.21

Once a model is designated as a general purpose model, then the firm must give an overview of all the training data that is specific enough that copyright holders may identify that their data was used, who then have the right to reserve to withdraw participation.22

If the model is classified as a systemic risk, the firm must then run additional risk assessments and evaluations, do life-cycle monitoring, report incidents to authorities, and implement more cybersecurity measures. Of course, certain uses of these models will also qualify as high-risk — meaning that all other compliance regulations also apply.23

The Authorities

The rules are bad. It gets worse once you look at how the regulations are actually enforced. In the preamble of the law it states that the purpose of the act is to ensure harmonization — that all 27 member states have the same policies and the single market runs efficiently.24

The reality of how enforcement is structured guarantees that the outcome will be fragmentation rather than harmonization.

At the EU level there will be four bodies: an AI office responsible for defining guidelines, definitions and coordinating bloc-wide enforcement, a Board staffed by representatives from the member states, a scientific panel, supporting both the office and the board, and an advisory forum.25

None of these EU bodies will actually be responsible for the vast majority of the act. While the laws were crafted at the European level, day-to-day execution will not be led by the commission but by multiple authorities within each country.

Each member state (in countries like Germany this may even be each Land) will have at least one Market Surveillance Authority responsible for ensuring compliance, investigating failures and applying penalties.26

Each member state will have at least one Notifying Authority that will supervise the organizations (called notified bodies) that do conformity assessments, and share those assessments with other Notifying Authorities.27

Each member state will also have notified bodies that are responsible for certifying that systems conform to the requirements imposed on them.28

For General Purpose AI Models, the relevant Market Surveillance Authority is the AI office, unless it qualifies as high risk, in which case both 27+ national Market Surveillance Authorities and the AI Office get to govern!29

By law, all these 55+ organizations must have staff with "in-depth understanding of AI technologies, data and data computing, personal data protection, cybersecurity, fundamental rights, health and safety risks and knowledge of existing standards and legal requirements.”30

Already EU bureaucrats have reported difficulties with staffing AI offices with real experts at the European level.31 Now imagine if we need an expert AI team for the Market Surveillance Authority of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

There are other issues with the enforcement worth mentioning.

Many of the obligations of the AI Act depend on self-reporting. Companies may decide, or at least are initially entrusted to decide, what risk category their model falls under. But beware if you get it wrong. If you violate a rule surrounding unacceptable risk you could be fined up to the higher of 35 million or 7% of global revenue.32 If you violate any other rule, the price is 15 million or 3% of global revenue.33

A lot of the definitions and codes of practice — for general purpose models, for the actual structure of conformity assessments and different impact assessments required — are not set yet.

Clear rules governing AI and copyright are absent, leaving both the training and output of generative models legally unclear.

According to some analyses, the European Union will need to develop approximately 60-70 additional pieces of secondary legislation to fully implement the AI Act.34

The consequences of this opaque system of rules and regulators are obvious. Compliance is a large fixed cost that forces concentration, penalizing start-ups for whom they are insurmountable. As we said with GDPR:

“It's like telling everyone they need to buy a $1 million machine to make cookies. Google can afford that, but your local bakery?”

Complexity benefits incumbents and larger firms. If you are an established player like META or Microsoft it is easier to navigate the 27 or more different MSAs. Good luck if you are a brand new startup with an educational or health tech system.

The express intent of the EU AI Act was to harmonize policy. It is counterproductive that the actual enforcement, monitoring, investigation and notification is devolved to tens of different member state authorities. Reminding us of the Woody Allen joke, the rules are bad and the enforcement is uneven.35

What went wrong

There seem to be two problems underlying the Act: a misunderstanding of where the gains from AI will actually accrue, and an unwillingness to let benefits and losses be incurred by free individuals in the market.

As we discussed in our piece last week, the largest benefits from AI will mostly concentrate around more sophisticated knowledge work. These are the kinds of AI which can operate unsupervised and interact with the world — for example by adding millions of drop-in remote workers in the form of AI agents.

It is these kinds of AI that the act penalizes most severely. As a heuristic, if an AI can make a decision which will impact someone in the world, it will be high risk and thus subject to onerous requirements. If an AI is large (trained using over 10^25 FLOPS, roughly today's generation of models already), it is also a general purpose model which poses systemic risk.

The models that are left untouched are the ones that do very menial work — e.g. filtering spam or formatting text. Indeed, AI models are allowed in high-risk activities if they "are intended to improve the language used in previously drafted documents, for example in relation to professional tone, academic style of language or by aligning text to a certain brand messaging."36

Hence, the AI Act is designed to allow us to easily capture the very minor gains that come from automating some of the simplest labor, but not many of the larger benefits that will come from having fully fledged AI agents interacting with the world.

There is a broader issue at play here: the AI Act tries to apply a product-based approach to a novel general purpose technology. It is as if in the mid-19th century one decided to classify certain uses of electricity — say home appliances — as high risk and subject to stringent regulations. What would that have done to the invention of the dishwasher?

The act follows from a belief that the EU must prevent any harm following from the deployment of a new technology, even those incurred by free citizens. Economist Eli Dourado has said before that the three rules governing innovation in the West today are:

No one may be harmed

No one may be inconvenienced

No jobs may be lost

The AI act is a clear example of this. Rather than let banks experiment with automatic AI tellers, biometric systems are categorized as high risk from the start and must be supervised by human monitors. Rather than let schools try and improve their quality by bringing in AI tutors, Europe preemptively says that there must be impact assessments, authorized representatives, notified bodies and monitoring.

This doesn't mean that innovation won’t happen — the gains are so large that it certainly will — but that diffusion is sclerotic, driven by large incumbents rather than dynamic startups, and fails to penetrate in areas like the public sector where efficiency gains might be largest.

I heard a story recently about a government department in a European country that had built a chatbot to query its own archives, only to be told by the legal department that it would fall afoul of regulation and was best shut off. One obvious consequence of the AI Act is that the gap between public sector and private sector productivity will grow even larger than it already is. It also means that the small startups that would be the best hope for developing European capabilities in this crucial area are unlikely to ever exist.

To be sure, many of the criticisms that AI firms currently have of Europe also stem from other existing regulations, not the new act. Meta has said data protection is why they are not releasing their new models in Europe, while Apple cites the DMA.

But the reason the impact of the Act is still limited is because many of its provisions are not yet enforced. The regulations will take effect in phases: prohibitions of certain AI systems begin in February 2025; rules for general-purpose AI start in August 2025; and requirements for high-risk AI systems will enter into force in August 2026.

The delay provides Europe with an opportunity to nullify the damage the Act can do before it takes force. There are smaller escape clauses: the commission has been given the power to amend Annex III, which lists high-risk use cases, and much of the enforcement practices are still up to be defined. Given the stakes, it would be better to start from scratch. The Commission has already committed itself to reviewing the Act in 2029. To escape the strange world of the EU AI Act, Europe should do that now.

"High-Level Summary of the AI Act." EU Artificial Intelligence Act. February 27, 2024. https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/article/31/

European Parliament and Council of the European Union. "Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of 13 June 2024 Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act)." Article 6, p. 53; and EU AI Act, Annex III.

EU AI Act, Article 6, p. 53; EU AI Act, Annex I.

EU AI Act, Article 9, p. 56.

EU AI Act, Article 10, p. 57.

EU AI Act, Article 11, p. 58.

EU AI Act, Article 12, p. 59

EU AI Act, Article 13, p. 59.

EU AI Act, Article 14, p. 60.

EU AI Act, Article 15, p. 61.

EU AI Act, Article 17, p. 62.

EU AI Act, Article 18, p. 63.

EU AI Act, Article 22, p. 65.

EU AI Act, Article 43, p. 78.

EU AI Act, Article 27, p. 69.

EU AI Act, Article 47, p. 80.

EU AI Act, Article 49, p. 81.

EU AI Act, Article 99, p. 115.

EU AI Act, p. 21.

EU AI Act, p. 49.

EU AI Act, Article 51, p. 83.

EU AI Act, Article 84, p. 53.

EU AI Act, Article 55, p.86.

EU AI Act, p. 1.

EU AI Act, Article 64-69, p. 95-99.

EU AI Act, Article 70, p. 99.

EU AI Act, Article 70, p. 99.

EU AI Act, Article 31, p. 71

EU AI Act, p. 40.

EU AI Act, Article 70, p. 100.

Espinoza, Javier. "Europe's Rushed Attempt to Set the Rules for AI." Financial Times, July 16, 2024.

EU AI Act, Article 99, p. 115.

EU AI Act, Article 99, p. 115.

Espinoza, Javier. "Europe's Rushed Attempt to Set the Rules for AI." Financial Times, July 16, 2024.

A waiter is told ‘the food is bad and the portions are small’

EU AI Act, p. 15.

Thank you for writing this. As an independent solopreneur in the AI space and software engineer, this all feels dreadful. The EU AI act, as well as other EU 'digital' regulation seems poised to destroy the European software industry, if not by intentet then by de facto outcome. Many of the EU software providers operate in a niche market, often bootstrapped by their owners. This industry is not ready to deal with the barrage of new EU regulationa, aka "the blue wall" - neither in terms of required legal expertise nor in terms of capital.

I think there is some sensibility in the heavy compliance requirements for those AI systems that are classified as "high-risk" under the AI Act. Do you want kids to be taught by an AI tutor? If they are, I think it's in order to do some safety testing and comply with a few documentation requirements. Sure, the AI Act wil have economic costs for AI companies but as a whole society will benefit from AI that is responsibly built and keeping humans accountable for any dangers and risks their AI systems may present.