Why tariffs won't save our car industry

The conditions are not right for a successful industrial policy

"Hence the undertakers of a new manufacture have to contend not only with the natural disadvantages of a new undertaking, but with the gratuities and remunerations which other governments bestow. To be enabled to contend with success, it is evident that the interference and aid of their own government are indispensible [sic].”

Alexander Hamilton, 1791, Report on the subject of Manufacturers

Last Friday, October 4, the European Union agreed to impose tariffs of up to 35.3% on battery electric vehicles imported from China after an investigation that found that Chinese automakers benefit from significant state subsidies. The hope in Brussels and other European capitals is that these measures will buy time for European car makers to become competitive in the EV segment. There's a genuine fear that if the market remains fully open, Chinese manufacturers could, within a few years, wipe out European car makers. While these tariff levels are far below the 100% tariffs imposed by the U.S.—which effectively shut out Chinese automakers—policy makers hope they might provide a brief window (maybe one or two years) for EU automakers to catch up.

To answer this question, observers are tempted to fight the old war on whether industrial policy can or cannot work. Instead, the real issue is whether the conditions for a successful industrial policy are in place in Europe today. In the case of EVs, the answer is negative.

Basic principles of industrial policy

Despite its supposed “revival,” governments never stopped relying on industrial policy. Regardless of pro-market rhetoric, governments defend the jobs of their voters in many ways, including trade barriers and other industrial policies. This includes famous free-market proponents such as Ronald Reagan, who protected cars, motorcycles, and steel, or Margaret Thatcher, who provided state aid to Japanese car manufacturers (Juhász et al. , 2023).

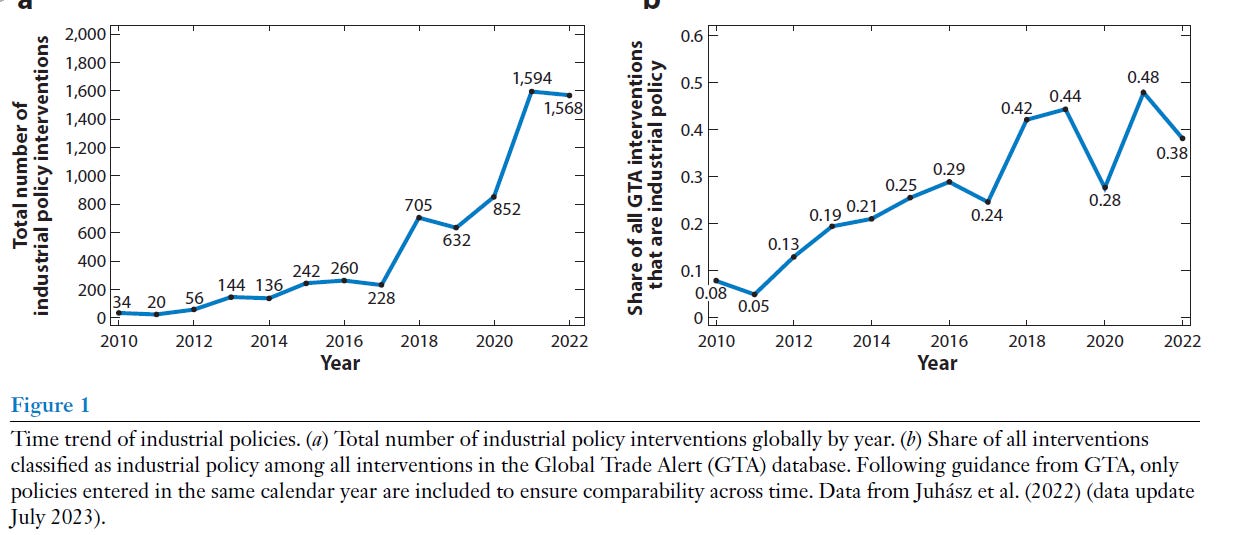

What has changed is the volume and explicitness of industrial policy, particularly of tariff and non-tariff protection for home industries. Many governments no longer pay lip service to the need to trade freely with other countries or allow their goods to pass through their borders.

Source: Juhász et al. (2023)

Contrary to myth, there is wide consensus among economists on the pros and cons of industrial policies. Industrial policy can improve market outcomes when market failures, such as externalities, coordination problems, or public goods, exist. For example, companies may underinvest in research and development due to imitation or knowledge spillovers; state subsidies can be used to encourage innovation. The market overproduces CO₂ because firms don't bear the full cost of emissions; various government interventions can help correct this. Or, as in the case of EVs, there's a chicken-and-egg problem: the value of an EV is low without charging stations, but building stations isn't worthwhile with few EVs. Subsidizing charging stations makes sense.

The case against industrial policy centers on the risk of corruption and cronyism. Politicians and bureaucrats may not maximize aggregate welfare but pursue their own interests like reelection, power, influence, and prestige. They can be captured by industry interests, and use the tools of industrial policy for their own benefit- a tariff to help a friendly industrialist will generate enormous gains to her, but impose diffuse and hard to measure costs on voters.

Economists views may differ on the balance between the benefits of correcting market failures against the costs of state failure due to corruption and cronyism. But there's less disagreement about where market failures are significant—climate externalities or clear public goods like defense or innovation—and where state capture is likely—where losers have political power, corruption is prevalent, and institutions are weak and captured by insiders.

Therefore, asking "do industrial policies work or not?" is the wrong question. The most free-market economist will agree they succeeded in Korea's heavy chemicals and industry essential for military survival (Lane 2022); Taiwan's semiconductor industry, created when the government attracted RCA, and then continued with the government as the main shareholder of TSMC; and China's solar panels, EVs, and shipbuilding (Barwick et al. 2021). The NASA Apollo program (Kantor and Whalley, 2023) and the Manhattan Project (Rhodes, 1986) were huge successes, creating important downstream benefits like nuclear energy.

But even economists of a more interventionist bent must agree that the world is plagued with industrial policy disasters. Consider the Jones Act, which aims to protect the U.S. maritime industry and national security. Passed in 1920, it requires all ships moving goods between U.S. ports to be American-built, owned, and crewed. The law raises shipping costs by 100 percent per day and creates absurd distortions. For example, New England imports liquefied natural gas from Russia instead of cheaper U.S. gas due to a lack of U.S. tankers from Texas. It has badly damaged Puerto Rico's development; the cost of shipping a container from New York to Puerto Rico is much higher than to Jamaica, which is only slightly farther (Grennes, 2017). Don't expect that, once passed a century ago, an obviously absurd law like this would be removable; the constituencies created are too strong.

There are hundreds of other examples in every developing and developed country, from Argentina and Venezuela to Italy and South Africa. That is why I would suggest to move beyond the debate of "yes/no to industrial policy" to the crucial question: Are the circumstances in a particular place and industry—the European car industry today—such that a specific industrial policy intervention is likely to be beneficial here and now?

To guide us in answering this question, we can turn to the most authoritative recent review of the literature by three proponents of industrial policy, including Dani Rodrik, one of the earliest and most prominent in this cycle (Juhász et al. , 2023). They suggest that the ability the ability to let losers go is a crucial criterion for success: "In the presence of uncertainty about both the effectiveness of policies and the location/magnitude of externalities, the ultimate test is not whether governments can pick winners, but whether they have (or can develop) the ability to let losers go."

Indeed, in 1960s South Korea, there were no entrenched losers—the state lacked incumbent workers and industrialists defending an existing industrial base. Bureaucrats could choose industries freely. Similarly, in early 2000s China, when decisive moves in cars, solar panels, and shipbuilding were made, insiders had minimal ability to resist. Not just due to the authoritarian, technocratic state, but because there were few losers—there was barely a homegrown internal combustion engine industry. With high growth rates, no constituencies were defending jobs.

Also, different problems require different solutions- an externality may require a tax or subsidy; coordination problems may not need subsidies. “Multiple goals require multiple instruments, a lesson that many governments have yet to internalize” (Juhász et al. (2023)). Hence a key criterion for success of industrial policy is for the policy makers to have a clear objective and to deploy one instrument to attain each objective.

Our discussion has considered industrial policy as a whole, but here we focus on tariffs. Tariff protection of an infant industry, like EVs, is the oldest form of industrial policy: shielding new home industries from international competition until they become competitive. This concept was first articulated by Alexander Hamilton in his 1791 Report on the Subject of Manufacturers. Translated into modern language, his words quoted at the start of this piece could be used unchanged by Ursula von der Leyen today. This form of industrial policy requires we add two additional caveats. First, tariffs can be opaque, with their incidence unclear to voters, making them easy for insiders to push and hard for consumers to remove. Second, imposing tariffs may lead to trade wars, impacting the entire economy.

The EU car industry

The EU car industry is struggling with a messy transition to EVs. EU law forbids the sale of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars from 2035.

Problems begin with the slow spread of charging points across Europe, despite high state subsidies, and the slow growth in demand. In China, 1 in 4 cars sold are EVs; in the EU, it's 1 in 7; in the U.S., 1 in 10. A slower transition limits economies of scale and increases transition costs.

Despite strong balance sheets and immense R&D spending (the top three R&D investors in the EU—VW, Mercedes-Benz, Bosch—are car and parts makers), European carmakers like Volkswagen, Daimler, BMW, Renault, and Stellantis have been unable to make the transition work. This isn't for lack of trying—Renault has withdrawn its first EV, the ZOE, after over a decade (according to safety test body NCAP it “offers poor protection in crashes overall, poor vulnerable road user protection and lacks meaningful crash avoidance technology, disqualifying it for any stars”), and BMW introduced the i3 in 2011. The problem may come to a head soon, as EU manufacturers are likely to miss the EU's interim targets, starting with a 15% drop by 2025 in average emissions intensity, and may face huge fines.

Evidence that Chinese manufacturers are ahead is detailed unsparingly by Draghi (2024b). First, EU car manufacturers have a 30% cost disadvantage compared to China. As a result, “The cheapest available new EV on the European market in 2023 was 92% more expensive than the cheapest available ICE car… in China… the cheapest available EV is 8% less expensive than the cheapest ICE car (i.e., a negative EV premium).”

Second, EU manufacturers have a significant technological disadvantage: “Chinese OEMs are one generation ahead of Europeans in terms of technology in virtually all domains, including EV performance (e.g. range, charging time, and charging infrastructure), software (software-defined vehicles, autonomous driving levels 2+, 3 and 4), user experience (e.g. best-in-class Human Machine Interfaces and navigation systems), and development time.”

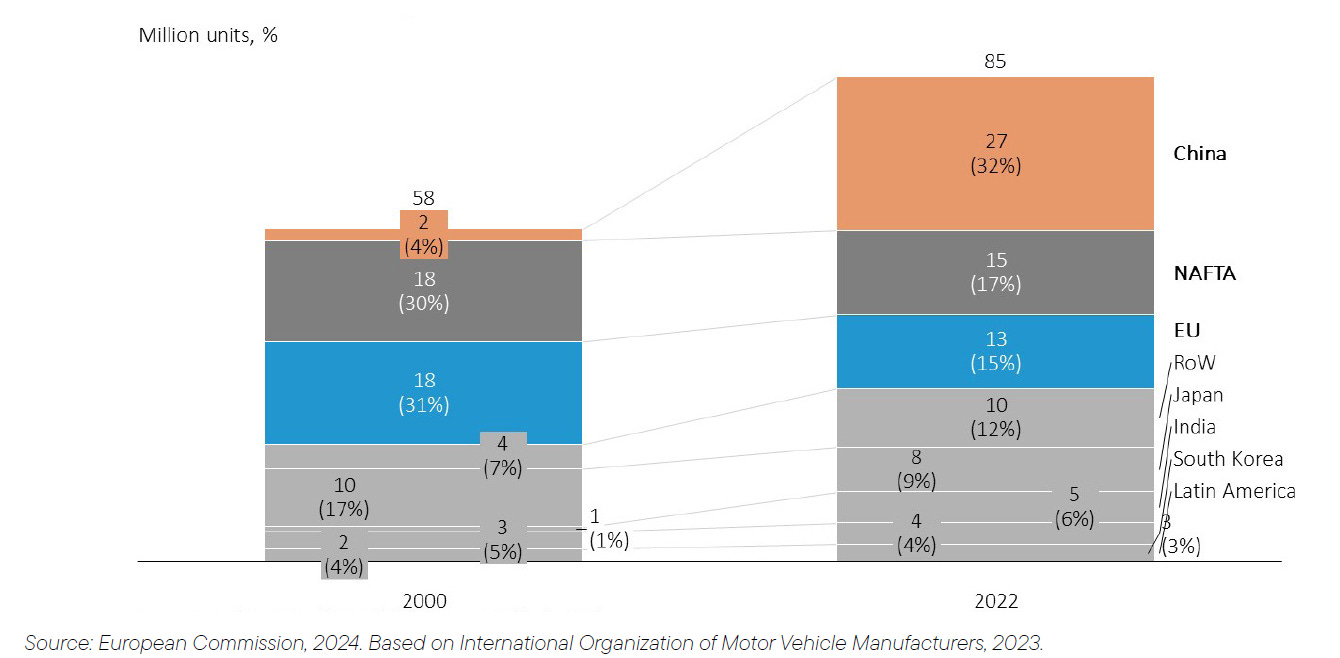

As a result, EU producers have gone from a world market share of one third to one sixth, while China's share has increased from the low single digits to 32%.

Source: Draghi Report (B), Chapter 6, Figure 2

That European incumbents, like incumbents everywhere, from Toyota to GM, struggle to produce EVs is unsurprising. EVs require entirely new vehicle designs, demand different manufacturing processes, rely on a new supply chain for batteries and rare materials, need workers to learn new skills, and depend heavily on advanced software and electronics. Moreover incumbents face fierce internal resistance from established organizational cultures. As a result, all successful EV producers to date worldwide are new entrants, most notably BYD and Tesla. This is not unusual for a radical innovation—see Kodak in digital photography, or IBM in PCs.1 More worrying for Europe is that no ex-novo EV manufacturers have appeared in Europe, versus dozens in China and (to focus on successful ones) Rivian, Tesla and Lucid in the US. Where is the young German engineer that after some tinkering, has come up with a good design and entered the EV market?

The stakes are high. The car industry employs 14 million people in Europe. If European carmakers can't keep up, the economic fallout could be huge—job losses, factory closures, and more. Plus, Europe's reliance on China for key parts like batteries puts it in a vulnerable position.

Are the conditions in place for successful industrial policy?

Returning to the two criteria:

Ability to Let Losers Fail: Europe’s car industry is dominated by legacy producers and workers who are (rightly!) fighting to preserve their place in the old order. Europe’s industrial system, with its high levels of protection for existing jobs, is not conducive to the type of creative destruction likely to engender new car manufacturing firms. The auto industry is too politically connected, and attempts to close plants will be met with fierce resistance from unions and manufacturers alike.

Clear and singular objective: Europe struggles between achieveing multiple and conflicting goals with this tariff. Should the focus be on combating climate change, in which case we should allow China to enter the market to accelerate green technology adoption? Is the priority geopolitical, in which case we need to focus on preventing data transmission abroad to protect national security? Perhaps competitiveness and future growth are the main concerns, suggesting a temporary prohibition while integrating with Chinese value chains (a strategy currently partly followed by Volkswagen e.g. with its Martorell assembly plant). Alternatively, if the goal is to protect existing industries to safeguard employment, closing the market and adopting a policy similar to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) might be the preferred (albeit extremely expensive) path. The result is a tariff that is too low to achieve the market closure that the US has sought with its 100% tariff (most likely, Chinese manufacturers will absorb the entire cost in their prices in their quest to penetrate EU markets), but too high if the objective is to achieve Europe’s green objectives. The fact that the level of tariffs is low is a result of these multiple objectives, and of the necessary compromises between many countries each of is seeking a different objective.

Without the capacity to let "losers" fail and a clear objective guiding policy, Europe's infant industry tariffs are unlikely to succeed in creating a successful set of EU EV producers, especially given the significant competitive advantages the Chinese EV industry holds today.

But what about national security?

We cannot discuss trade with China today without considering national security. In the particular case of EVs, the main concerns are data privacy and manipulation. Chinese automakers could collect sensitive information on citizens and infrastructure, enabling surveillance through real-time tracking and behavioral insights. Additionally, software in automated driving systems could allow malicious actors to remotely manipulate or disable vehicles.

The U.S. government has proposed rules to ban the import or sale of certain connected vehicle systems linked to China or Russia. What does this mean for Europe? If national security is the true concern, Europe must be clear about this rationale and pursue specific measures to protect its interests, much like the U.S. has done. A tariff that increases prices by less than a third isn't designed to, and cannot achieve, that result.

What Is the alternative?

First, the EU should focus on creating public goods—a major reason for low demand is insufficient charging infrastructure. There's a strong case for state intervention here.

Second, if it cares about this industry, Europe should streamline the regulatory environment which affects it. Draghi finds (to my surprise and immense chagrin) that many of the Green Deal rules are aspirational and internally inconsistent, creating confusion for automakers. For example, he points out that the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) excludes Scope 3 emissions (indirect emissions from production inputs not directly controlled by the company), while the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) includes them, subjecting the same imported material to two different CO₂ figures under the two regimes. Also, new laws have been initiated by different Commission services (DG GROW, TRADE, CLIMA, ENV, and FISMA) without a central body coordinating timing and assessing their impact on the industry. This is a really serious problem I will come back to in a later post. But it is clear that if Europe wants to help its EV transition, it must start by streamlining regulations.

A third approach, which manufacturers and EU countries like Italy, France, or Spain might have in mind with these moderate tariffs, is to partner with Chinese manufacturers. Governments hope Chinese producers will interpret this as an invitation: "Come produce here, don't try to destroy us." Given their technological lag, EU producers may seek investments from Chinese manufacturers to gain know-how, batteries, and low-cost platforms.

However, beyond national security risks, there's the danger for EU manufacturers of becoming mere assemblers of foreign technology. For example, Martorell, Spain's flagship VW (Seat) manufacturing base, recently announced a €300 million investment for a plant to assemble batteries,—the low-cost, low-knowhow final stage of manufacturing. It's doubtful whether any know-how or competitive ability is transferred.

Conclusion

Imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs is unlikely to rescue Europe's auto industry from its current challenges. The essential conditions for successful industrial policy—allowing failing companies to exit the market and having a clear, singular goal—are missing. Europe's car industry is dominated by established manufacturers resistant to change, and the policy objectives are muddled, ranging from fighting climate change to protecting jobs and addressing national security concerns.

Even though the tariffs are unlikely to work, at this point Europe probably has no alternative but to try to gain some time. Tariffs are probably needed. At the same time, Europe should focus its policies on areas where government action can make a real difference. Investing in electric vehicle infrastructure, like charging stations, is crucial to boost demand and provide economies of scale for parts and automakers. Simplifying and clarifying regulations would also help automakers adapt and compete globally. If the purpose of the tariffs is to open the door to collaboration and joint ventures with Chinese manufacturers, this needs to be openly discussed, and its national security repercussions considered.

References

Barwick, Panle Jia, Myrto Kalouptsidi, and Nahim Bin Zahur. Industrial Policy Implementation: Empirical Evidence from China's Shipbuilding Industry. Washington, DC, USA: Cato Institute, 2021.

Draghi, Mario. 2024b. "EU Competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations" EU Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Garicano, Luis, and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. "Organizing growth." Journal of Economic Theory 147, no. 2 (2012): 623-656.

Grennes, Thomas J. "An economic analysis of the Jones Act." Mercatus Research (2017).

Juhász, Réka, Nathan Lane, and Dani Rodrik. "The new economics of industrial policy." Annual Review of Economics 16 (2023).

Kantor, Shawn, and Alexander T. Whalley. Moonshot: Public R&D and growth. No. w31471. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023.

Lane, Nathan. "Manufacturing revolutions: Industrial policy and industrialization in South Korea." Available at SSRN 3890311 (2022).

Rhodes, Richard (1986). “The Making of the Atomic Bomb.” New York: Simon & Schuster.ISBN: 978-0-671-44133-3.

See Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg (2012) for a review of the evidence and a theoretical model where firms build hierarchies to organize the acquisition of specialized expertise about the old technology and where the new technology is incompatible with the existing organization.

pre-condition ‘to let losers go’: thanks for highlighting.