If a problem in the financial system were to emerge, given the current market turmoil, where would it emerge?

Three outstanding/current recent research papers shed light on three distinct, yet interconnected, fault lines, to use Raghu Rajan’s book term: one in the core Treasury market, another due to bank balance sheets (especially linked to commercial real estate), and a third involving hidden risks in banks' commitments to non-bank lenders.

1. The Treasury Market's Fragile Foundation

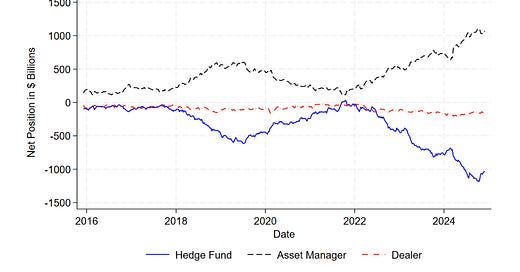

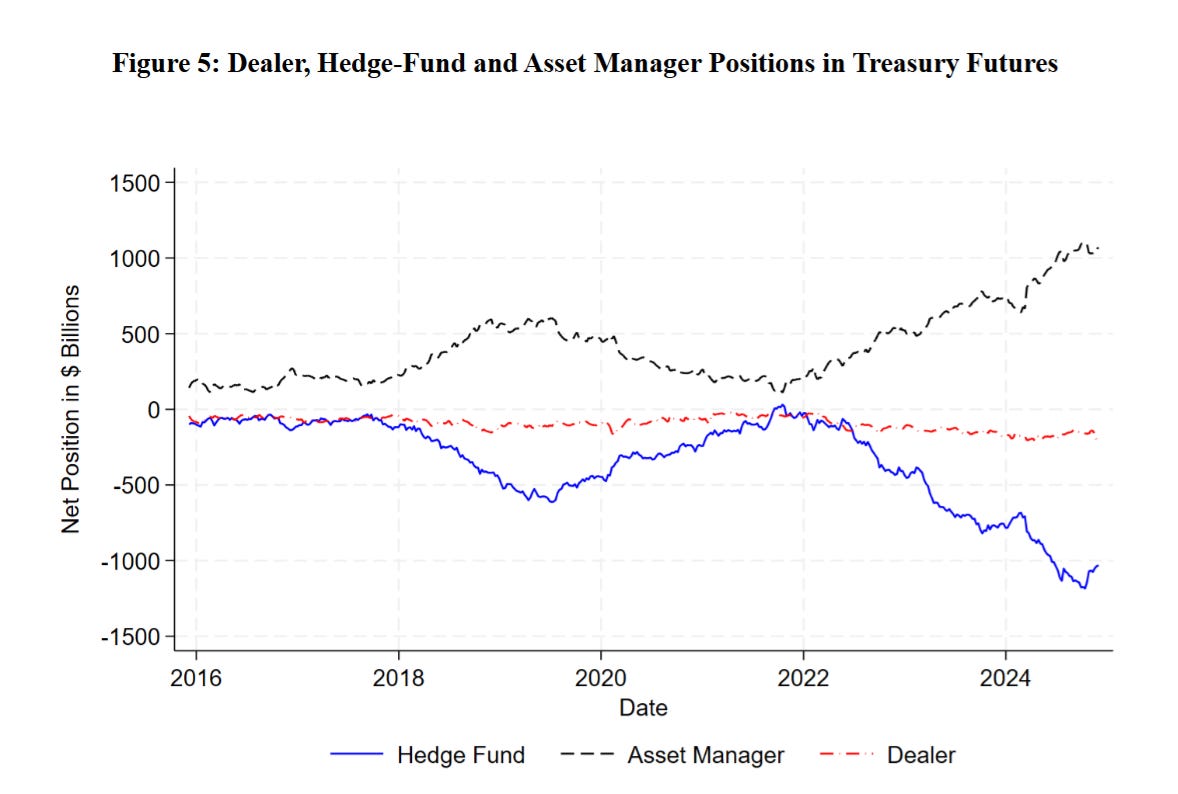

The market for U.S. Treasury bonds is critical but a March 2025 paper by Kashyap, Stein, Wallen, and Younger (March 2025) highlights a growing fragility. The issue centers on the “cash-futures basis trade.” Hedge funds buy cash Treasury bonds and sell Treasury futures, aiming to profit from tiny price differences. While seemingly low-risk, the danger lies in extreme leverage: hedge funds finance these cash bond purchases almost entirely through overnight repo borrowing. By late 2024, hedge funds held over $1 trillion in these leveraged positions.

The vulnerability crystallizes during market stress. Events like the March 2020 turmoil showed that shocks (like margin calls) can force hedge funds into rapid "fire sales," unwinding both their cash bond holdings and futures positions simultaneously. Broker-dealers (such as Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley) must initially absorb these sales, but their capacity is limited by regulation and risk appetite. When dealers become overwhelmed, market functioning breaks down: the basis spread widens sharply, trading liquidity evaporates, and repo market funding tightens. This isn't just a niche market issue; it threatens the plumbing of the entire financial system. (See the paper, it is very clear.)

2. The CRE Shadow Over Banks

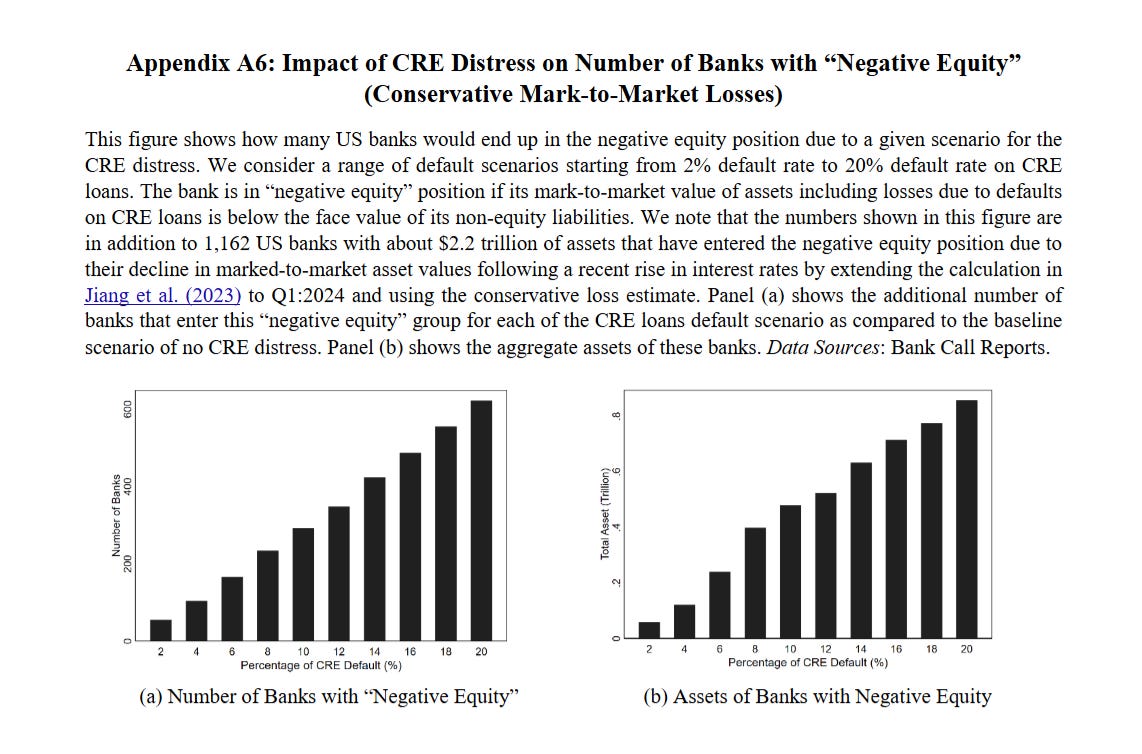

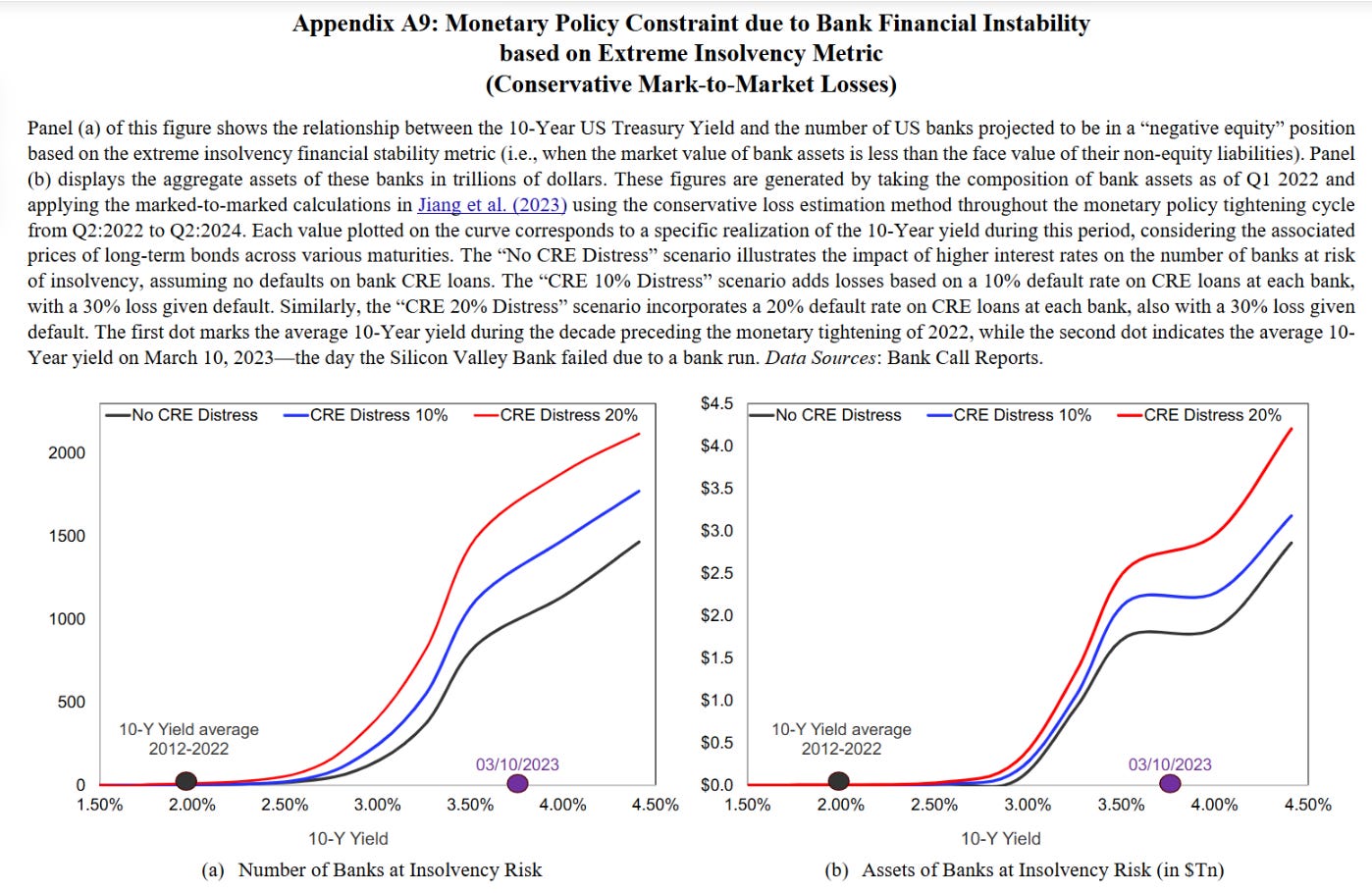

A different vulnerability emerged with the Federal Reserve's rapid interest rate hikes starting in 2022. An October 2024 paper by Jiang, Matvos, Piskorski, and Seru (JMPS) which we already covered in this blog (in “Do we need banks?”, with thanks to Amit Seru) quantifies the impact. They estimate that rising rates slashed the market value of U.S. banks' assets—primarily long-term bonds and loans bought when rates were low—by $2 trillion. This massive unrealized loss significantly weakened banks' ability to absorb shocks.

Compounding this interest rate shock is distress in Commercial Real Estate (CRE), fueled by higher borrowing costs and shifts to hybrid work. The JMPS paper finds that around 14% of all CRE loans (and 44% of office loans) may have been in “negative equity” by late 2023/early 2024, with many facing refinancing challenges. While potential direct losses from CRE defaults (estimated at $80-$160 billion for 10-20% defaults) are much smaller than the interest rate hit, they land on an already weakened banking sector.

The mechanism for failure here involves depositors. If uninsured depositors perceive a bank is weak—due to the combination of asset value declines from rate hikes and potential CRE losses—they may “run,” withdrawing funds. Even if a bank's assets are technically liquid (like Treasuries), being forced to sell them at depressed market values to meet withdrawals can make the bank insolvent. JMPS estimate this combined stress puts dozens to over 300 banks, mostly smaller regional ones with high CRE exposure, at risk of such runs. This fragility constrains monetary policy, as further rate hikes could push more banks toward insolvency.

3. Banks' Hidden Lifelines to Shadow Banks

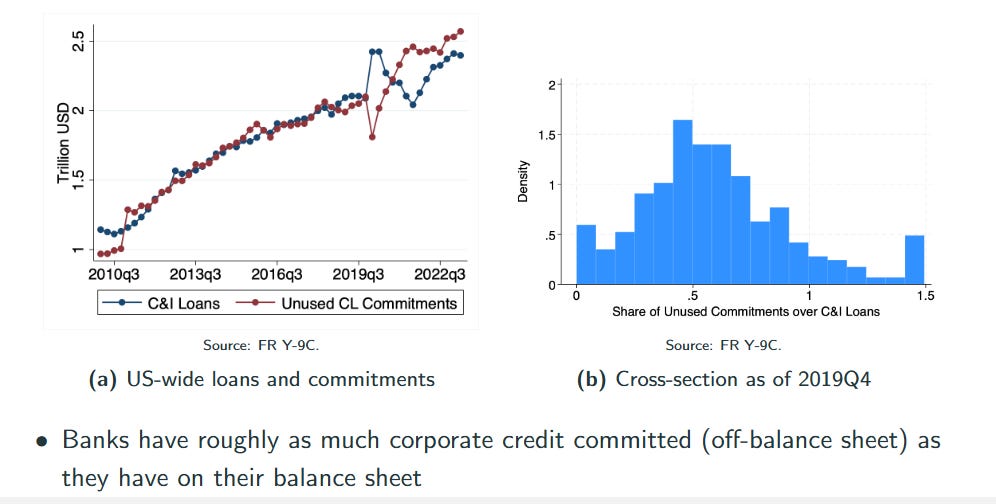

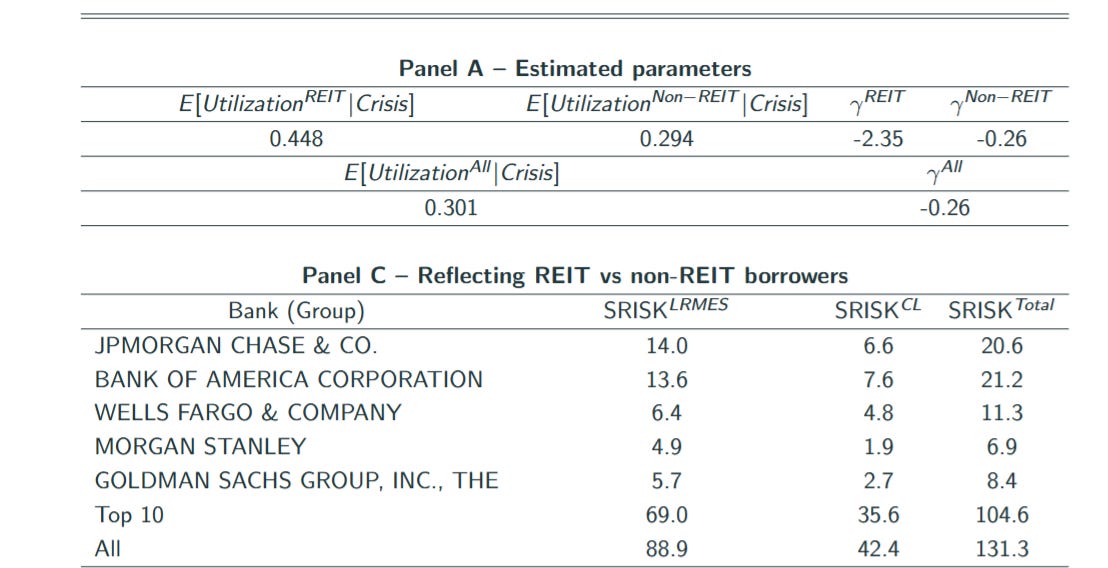

We have seen that banks are exposed directly to the commercial real estate market through loans, and that this risks is concentrated in small banks. But a paper by Acharya, Gopal, Jager, and Steffen (AGJS), (here is the paper, here are the very clear slides) show that banks are also exposed to CRE — and to much other private credit risk— through credit lines to non-banks. Banks provide huge, often off-balance-sheet, credit line commitments to Non-Bank Financial Intermediaries (NBFIs). These commitments function as liquidity backstops for NBFIs like REITs, which invest heavily in CRE but often hold little cash. The scale is immense: banks have roughly as much credit committed via lines as they have loans on their balance sheets. While smaller banks hold most direct CRE loans, large banks have significant indirect exposure through these lines to REITs.

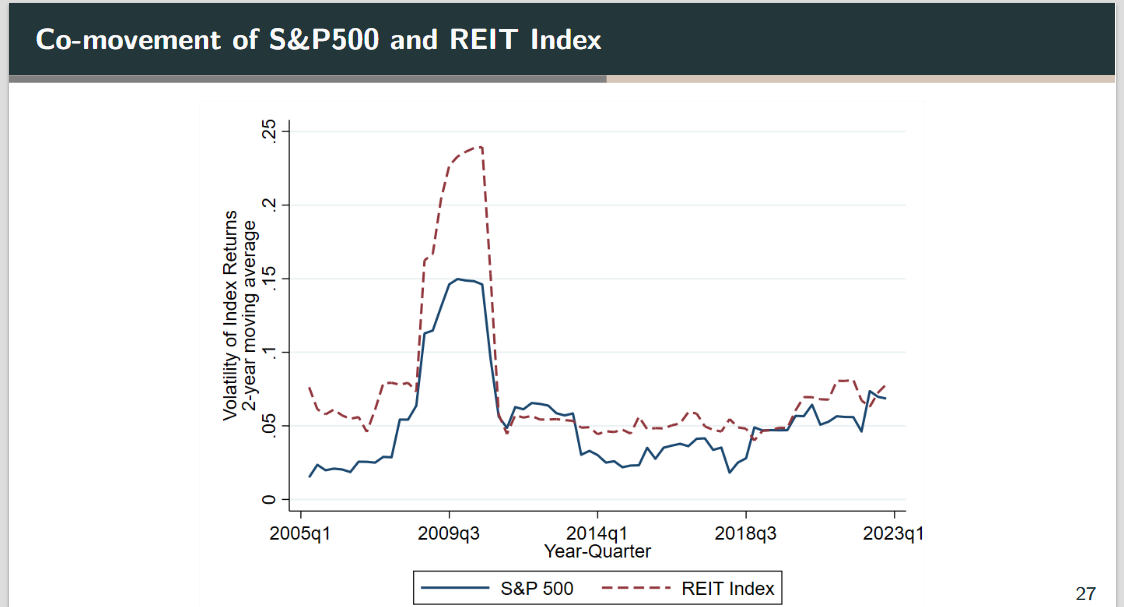

The vulnerability arises because NBFIs, especially REITs, draw heavily and simultaneously on these lines during crises. When a credit line is drawn, it becomes an immediate loan on the bank's balance sheet. This forces banks to suddenly fund large new assets and hold capital against them, straining their resources precisely when markets are stressed. The AGJS paper (see the presentation) shows banks with higher exposure to REIT credit lines performed worse during crises like COVID-19, indicating these lines transmit risk from the non-bank sector (and its CRE exposure) directly into the banking system, affecting even the largest players. Accounting for these links substantially increases measures of systemic risk.

One last point: REITs comove with the S&P.

The current turmoil

Stress in one corner of the financial system can trigger a chain reaction that affects all three fault lines at once. A spike in Treasury market volatility can push leveraged hedge funds to dump bonds and futures, tightening short-term funding and hurting dealers’ balance sheets. That shock can then reach banks already weakened by rate-driven asset losses and commercial real estate problems. As banks scramble to meet deposit withdrawals or keep enough capital to support defaulted CRE loans, they may cut off—or face sudden draws on—the credit lines that sustain REITs and other non-banks. This hidden interdependence raises the risk of self-reinforcing disruptions, where forced selling and funding pressures spread through the system.

The current environment amplifies these connections. A heavier Treasury issuance and a potential withdrawal from sovereign buyers from the Treasury market increases market volatility and the risk on the hedge funds’ basis trades, creating more leverage risk. Increases in risky rates push more CRE loans underwater, intensifying pressure on mid-sized and regional banks. Non-banks, starved for liquidity, place bigger demands on pre-committed credit lines from large banks. Together, these elements form an underappreciated web of exposure.