On March 19th, twelve European research ministers, led by France, called on the European Commission to take “immediate action” to “welcome brilliant talents from abroad who might suffer from research interference and ill-motivated and brutal funding cuts”. They propose using several European funding mechanisms, including the European Research Council, Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, and ERA Talents, together with a dedicated “immigration framework” to make it easier for talent to come to Europe.

The intention is good. But will simply opening our doors and promising funding be enough?

I believe not. The problem with our universities is not just a lack of funding and low salaries (although these matter, as we have written here before). It is poor incentives.

Here is a simple model for how universities currently work on the two sides of the Atlantic.

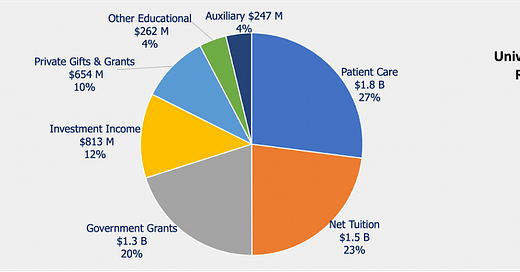

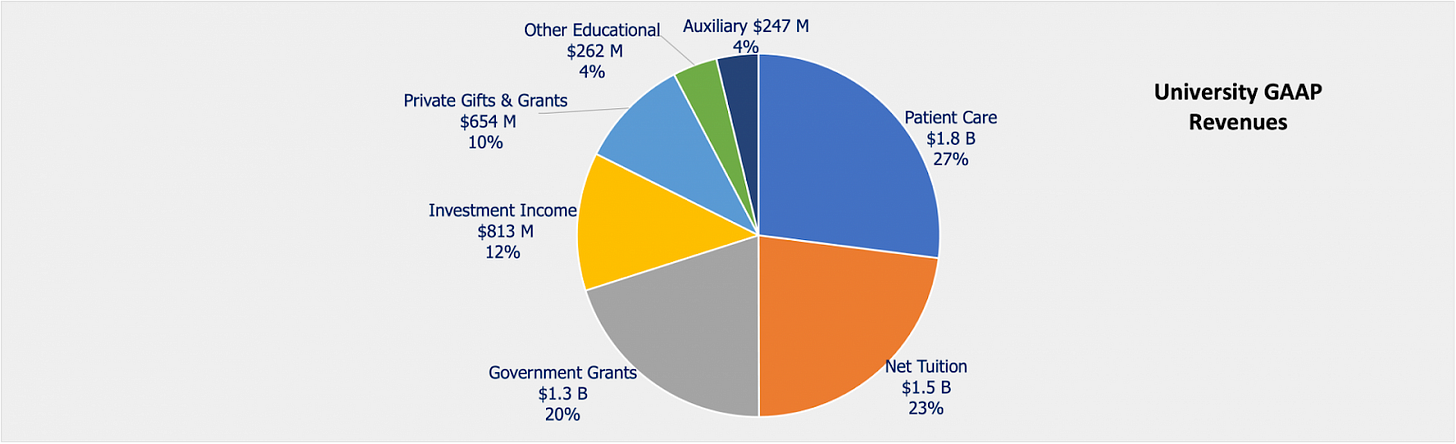

In the United States, universities operate like investment firms. Major institutions manage large endowments —notably Harvard with $53.2 billion and Stanford with $38 billion — and deploy funds selectively toward researchers and labs.

Universities invest strategically because their income depends on performance. Private philanthropy and tuition follow prestige, as do competitive federal grants awarded via peer review. Daily operations rely heavily on indirect cost reimbursements from research grants, which can exceed 60% for on-campus research at top institutions, as well as on endowment distributions and tuition.1 At Columbia, for instance, federal grants are as large a share of income as tuition revenue.

It is reasonable, if slightly provocative, to think of American universities as for-profit enterprises: they pursue prestige to attract tuition fees and donor funds, compete aggressively for grants, and seek patent income. Hence, they generously reward scientists who maximize publication counts, citation impact, grant dollars, and patent revenue.2

In contrast, European universities resemble civil service bodies. Their main revenue comes from fixed government allocations, largely independent of performance. Tuition is mostly funded by the state budget, with prices set politically, far below costs and independently of performance (all universities cost the same). Grant overhead is largely irrelevant. In turn, professors are essentially civil servants, paid like them, gaining little but prestige for great work. Pay is not always too low. For some faculty doing minimal research and indifferent teaching it is, if anything, too generous – which explains the immense resistance within European academia to any increase in accountability and competition.

This system creates entirely different incentives. In Europe, neither the scientist nor the university receives the upside of major success, as public funding, tuition, and philanthropy are all basically insensitive to performance.

Crucially, if incentives are misaligned, greater spending does not improve performance. An evaluation of two large funding programs implemented by France and Germany in the last decade illustrates this concern.

In Germany, much frontier research takes place outside universities, in institutes like Max Planck and Fraunhofer. Public universities are state-funded, controlled by regional governments (Länder), and have limited autonomy. Hiring is constrained by civil service rules (in fact, salaries are fixed at civil service scales and top out at the secretary of state level).

Since 2006, Germany's Excellence Initiative (renamed Excellence Strategy in 2019) has aimed to create globally competitive universities attractive to international talent. Managed by the German research and science councils (DFG and Wissenschaftsrat) rather than directly by government ministries, the program directs substantial funding – currently over €530 million annually and set to increase – through competitive selection. Key components support specific research 'Clusters of Excellence' and provide long-term institutional funding ('Universities of Excellence', formerly 'Zukunftskonzepte') to selected universities striving for top-tier international standing. As of 2024, there were 57 Clusters of Excellence and 11 Universities of Excellence.

The French system is similar to the German one —universities have weak central leadership, research is done outside universities, and professors are paid like civil servants. Professors have careers that are regulated nationally, and universities lack the ability to select undergraduates, unlike the better-funded Grandes Écoles. (Hence, uniquely, the French elite has traditionally been educated outside the university system.)

In 2009, like in Germany, the government launched the “Initiative d’Excellence,” a large investment plan administered outside the education ministry to create a few world-class universities. Selected by an international committee, eight initial sites were created (often by merging existing institutions). The grants (averaging €0.8 billion) were held in endowments managed centrally, with universities receiving yearly investment returns (around 3%) rather than the capital itself.3

Carayol and Maublanc (2025) provide the first systematic analysis of these German and French programs. Using a difference-in-difference approach with matched European universities as controls, they found that excellence funding did have “a positive direct impact on treated universities” with increases of 7-13% in scientific outcomes.4 The analysis finds that one million euros in excellence funding led to approximately 22.5 more scientific articles, including 19 international collaborations and 2.5 industry partnerships.

However, impact “does not concentrate on top-cited papers but is larger on the internationalization of research and on collaborations with industry.” The effect on highly-cited papers was positive but not statistically significant–these programs didn't raise universities to true world-class research status.

Critically, their event study analysis revealed that:

“excellence policy prevented most treated universities from losing their scientific competitive edge, whereas the competitive position of non-selected universities in those countries have essentially waned both in their national and in the European context.”

In other words, excellence funding primarily prevented funded universities from losing ground rather than propelling them forward in global rankings–while the “untreated” peers continued their downward slide.

What is missing for success is a radical change in governance. A study by a team of leading economists (Aghion, Dewatripont, Hoxby, Mas-Colell, and Sapir, 2010) found a strong positive link between university performance (measured by international rankings and patent output) and two crucial factors: autonomy and competition.

The best-performing universities, both in Europe and the U.S., are those with greater independence from political and administrative powers. This includes budget control without constant government approval, flexibility to set faculty salaries based on merit, control over hiring faculty and admitting students, and independence in designing curriculum.

Autonomy works best when universities are pushed toward excellence by competition. Universities are more productive when they must compete for funding through grants and vie with other institutions for the best faculty and students.

To establish a causal link, Aghion et al. (2010) studied the effects of an unexpected increase in funding. To isolate such unexpected funding shocks, they used specific political processes: changes in state representation on powerful federal funding committees (driven by unpredictable vacancies) served as an instrument for research university funding, while changes in the colleges located in the districts of state-level committee chairs served as instruments for state funding of 4-year and 2-year colleges. They concluded that more autonomous and competitive universities turn unexpected funding increases into more patents.

The problem is that, across Europe, both competition and autonomy are missing. In Italy and Spain, like in France and Germany, professors are civil servants, and there is no real autonomy for the universities (except through borderline legal engineering like in Catalonia). Italy's Gelmini Reform (Law 240/2010) restructured governance and expanded performance-based funding, but autonomy remains constrained by state rules on hiring and salary caps.

Perhaps the most telling case is Belgium, which shows a stark contrast between two approaches. Flanders has embraced high autonomy since 1991. As the Aghion et al. results would suggest, strong performance followed, with KU Leuven often ranked in or near the top 50 globally and Ghent University showing success in European Research Council grants. Meanwhile, in Wallonia-Brussels, funding is still mostly historical and enrollment-based, and oversight is more centralized. Universities like UCLouvain and ULB lag behind their Flemish counterparts in rankings.

There have been some successes. The Netherlands introduced performance agreements linking some funding to targets and expanded competitive grants. Probably as a result, the Dutch universities have performed well in the international rankings, with multiple universities in the global top 100, and enjoy strong international recruitment. Sweden enacted a major Autonomy Reform (2011), deregulating internal organizations and granting more staffing freedom. While universities remain state agencies, they've seen increased flexibility and maintained strong research performance.

At the EU level, the European Research Council (ERC) is a valuable move toward competitive, merit-based funding. It encourages high-quality research and rewards excellence directly, rather than distributing resources politically. It changes incentives a bit, but it doesn’t change universities’ ability to respond to them.

Funding and visas cannot compensate for a lack of freedom. Europe's universities will not rise until they are able to hire, fire, pay, and admit on merit—and forced to compete. Autonomy and competition, not slogans or subsidies, are what build excellence. Without freeing universities from bureaucratic control, additional funding and immigration schemes will (in a manner similar to Carayol and Maublanc’s findings) merely delay Europe's scientific decline, not reverse it.

References

Aghion, Philippe, Mathias Dewatripont, Caroline Hoxby, Andreu Mas-Colell, and André Sapir. "The governance and performance of universities: evidence from Europe and the US." Economic policy 25, no. 61 (2010): 7-59.

Carayol, Nicolas, and François Maublanc. "Can money buy scientific leadership? The impact of excellence programs on German and French universities." Research Policy 54, no. 2 (2025): 105155.

The NIH introduced in February a standardized indirect cost rate of 15% for all grants, which has been blocked by a federal judge.

Research by Raj Chetty and coauthors (this particular paper is astonishing in scope and execution) shows that, for all the protestations of the Universities, tuition revenue and aid is largely a game of price discrimination, driven by profit maximization.

Differently from the German system, the French one tried to also game the international rankings by pushing universities to merge into larger entities like Paris-Saclay and PSL – an initiative that succeeded as Paris-Saclay entered some of the top 15 ranks globally.

Specifically, they control for “university fixed effects, yearly university spending (to account for the variation over time of other sources of funding), country-year fixed effect accounting for any country specific yearly shock and any national trend, and regional R&D”, Carayol and Maublanc (2025).