As we have documented in this blog, the EU has made many mistakes on innovation. Competition enforcement is not one of them. Yet the mission of the new competition commissioner, Teresa Ribera, acting on the Draghi report’s recommendations, is to abandon existing (and good) antitrust rules in favor of discretionary political decisions.1 These changes are meant to engender innovation and the green transition. Instead, they risk enabling crony capitalism and regulatory capture, fragmenting the single market, and ultimately damaging EU competitiveness.

The Ordoliberal Foundation

To understand European antitrust you need to look back at the Ordoliberal school, developed at the University of Freiburg in the 1930s and 1940s by Walter Eucken, Franz Böhm, and others. Having observed how economic concentration enabled Nazi totalitarianism, these ordoliberals argue that dispersed economic power is essential for both market efficiency and democratic stability. This intellectual legacy shapes the EU’s focus on competitive market structures, rather than solely on price effects. For ordoliberals, antitrust is a constitutional safeguard for a free society—a concept they called the “economic constitution.”

Of course, Europe’s antitrust has evolved beyond insights developed midway the 20th century. In a mix that competition law expert Pablo Ibañez calls the “Brussels Consensus,” it has incorporated modern economic insights. This shift began under Mario Monti with the creation of the Chief Economist office in DG Competition (DG Comp). According to Ibañez, this has ensured that EU competition policy aligned with mainstream economic thought. Research on network effects and platform competition has, for instance, supported interventions in digital markets.

It is this philosophy that informs DG Comp’s skepticism toward high market shares and efficiency defenses.

When firms argue that mergers will create efficiencies, the Commission demands concrete evidence rather than relying on theoretical claims. The approach has three main legal pillars: rules against anticompetitive behavior under Articles 101 and 102 of the EU Treaties (TFEU); merger control to prevent harmful consolidation; and state aid rules to avoid wasteful subsidy races between member states.

The latter two pillars are now under attack. Critics argue that merger rules prevent firms from achieving sufficient scale and that state aid rules block industrial policy initiatives. State aid rules have already been weakened by successive “Temporary Frameworks” during crises, a topic for a future blog. Here, the focus is on merger control.

Two critiques

The first group of opponents of Europe’s approach come from the laissez-faire tradition. They argue that market self-correction through free entry makes strict antitrust enforcement unnecessary. Frank Easterbrook’s influential 1984 article contended that errors in blocking procompetitive behavior (Type I errors) are costlier than permitting anti competitive actions (Type II errors), as entry and future competition makes excessive market power due to the last type of errors temporary.

Other Chicago scholars like Richard Epstein have criticized EU merger rules for their structural bias against large-scale consolidations, arguing they overlook dynamic gains from scale. Dynamic competition theorists, such as Nicolas Petit, argue that large firms compete through sequential innovation across markets, a dynamic traditional market definitions miss.

The second (interventionist) critique comes from advocates of industrial policy, who argue that the EU’s antitrust approach prevents European firms from achieving the scale needed to compete globally. Drawing on strategic trade theory and Schumpeterian economics, they claim merger rules and state aid restrictions stifle innovation by limiting firms' ability to invest in R&D, attract talent, and compete with U.S. and Chinese giants. The Draghi report argues that Europe risks falling behind in critical technologies unless it allows large innovative companies to emerge.

Meanwhile, the interventionist premise — that there is a clear link between ‘scale’ and innovation — is not straightforward. Larger firms often have greater resources to spend on R&D, but simply growing firm size or increasing concentration does not guarantee more innovation. Instead, scale can allow incumbents to capture economic rents and reduce the competitive pressure that spurs new ideas.

Empirical evidence from various industries, including pharmaceuticals and telecommunications, shows that firms with entrenched positions often enjoy steady profits without making commensurate investments in innovation. Research by Aghion et al. (2005) demonstrates an inverted-U relationship between competition and innovation, suggesting that neither too little nor too much market power is optimal for technological progress.

Studies such as Blonigen and Pierce (2016) have found that mergers expected to yield efficiency and R&D gains often fail to deliver, while Cunningham, Ederer, and Ma (2021) show that firms often acquire competitors to suppress innovation rather than enhance it.

Both critics overlook how economic concentration creates political power. Large firms often manipulate regulatory environments to entrench their dominance. As George Stigler noted in his seminal work on regulatory capture, incumbents lobby for complex regulations to raise barriers to entry. Economists like Luigi Zingales and Raghuram Rajan argue that capitalism must be protected from capitalists, whose profit-maximizing behavior often undermines competition.

Empirical studies underscore this. Cowgill, Prat, and Valletti (2021) found that mergers among publicly listed firms in the U.S. led to a 30% increase in lobbying expenditures. Similarly, Gutiérrez and Philippon (2017) showed that firms in concentrated industries spend more on lobbying, linking concentration to regulatory capture.

Why Europe’s Approach Works

The reality is that european competition policy has led to better consumer outcomes across many sectors. Consider telecoms. For critics like the Draghi report, lower telecom prices in Europe have reduced profitability and thus curbed investment and innovation:

“Lower prices in Europe have undoubtedly benefited citizens and businesses but, over time, they have also reduced the industry profitability and, as a consequence, investment levels in Europe, including EU companies’ innovation in new technologies beyond basic connectivity.”

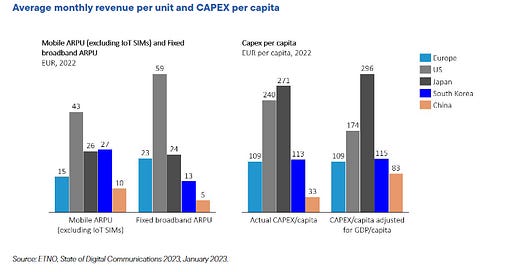

Yet lower prices clearly benefit consumers, and there is no evidence that telecom incumbents drive meaningful technological progress. The EU’s approach—blocking domestic duopolies like TeliaSonera/Telenor in Denmark or proposed 4-to-3 consolidations like O2-Hutchinson in the UK—has delivered not only lower mobile prices (around €15 monthly in Europe versus €43 in the U.S.) but also robust data traffic growth.

I agree that we may often want to have larger firms (on this blog we have talked much about the benefits of superstars). But it is regulatory fragmentation, not antitrust enforcement, that has prevented national incumbents from cross-border mergers that would preserve competition. In fact, many genuinely cross-border combinations that do not harm competition, such as the merger that created Stellantis from PSA and Fiat Chrysler, have been approved because they did not reduce consumer choice or raise entry barriers.

It is not just in Europe that policymakers indulge the illusion that bigger equals better. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) claims it can allow a mega-operator merger like Vodafone-Three—creating an operator serving 27 million customers—and then rein it in later through regulation. Britain’s experience with privatized utilities proves otherwise: monopolies like Thames Water easily outmaneuver regulators, raising prices and cutting service quality. Allowing dominant firms to emerge does not foster innovation or better services; it creates entrenched power that resists accountability.

The New Dirigisme

The Draghi report and Ribera’s mission letter propose diluting competition rules by broadening market definitions, invoking speculative “dynamic efficiencies,” and relaxing state aid constraints. These changes would gut the economic foundations of competition enforcement in favor of political discretion. The result would be national champions or duopolies that raise prices, undermine competition, and fail to deliver genuine innovation.

The EU must not let desperation over competitiveness lead it to politicize its competition policy. Weakening antitrust enforcement and state aid rules would fragment the single market and empower incumbents who thrive on connections rather than merit. This new dirigisme—a mix of politicized antitrust, lax state aid, and unchecked rulemaking—would cripple what remains of market-driven dynamism in Europe’s economy, and reward political access over better ideas.

They may seem flashy in the short-term, but the creation of large state-backed champions in Europe would be a decision that leaders would surely come to regret. Crony capitalism destroys innovation by substituting political influence for market competition.

As EU leaders panic about losing ground to the U.S. and China, they risk dismantling the very institutions that sustain prosperity and integration. Without a single market, there is no European Union. If, as Draghi and Letta note, Europe’s greatest problem is the absence of a true single market, then expanding loopholes for national champions guarantees more fragmentation and no real technological progress.

Instead of gutting competition policy, the EU should simplify regulation, maintain strong antitrust enforcement, and ensure a genuinely integrated single market. EU antitrust works. Sacrificing it in the name of “competitiveness” would be a fatal error.

References

Aghion, Philippe, Nick Bloom, Richard Blundell, Rachel Griffith, and Peter Howitt. “Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 2 (2005): 701–728.

Blonigen, Bruce A., and Justin R. Pierce. “Evidence for the Effects of Mergers on Market Power and Efficiency.” NBER Working Paper No. 22750, 2016.

Cowgill, Bo, Andrea Prat, and Tommaso Valletti. “Political power and market power.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.13612 (2021).

Cunningham, Colleen, Florian Ederer, and Song Ma. “Killer Acquisitions.” Journal of Political Economy 129, no. 3 (2021): 649–702.

Easterbrook, Frank H. “The Limits of Antitrust.” Texas Law Review 63 (1984): 1–40.

Epstein, Richard A. Antitrust Consent Decrees in Theory and Practice. Washington, D.C.: AEI Press, 2007.

Gutiérrez, Germán, and Thomas Philippon. “Investmentless Growth: An Empirical Investigation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 2 (2017): 89–169.

Ibáñez Colomo, Pablo. The New EU Competition Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2023.

Petit, Nicolas. Big Tech and the Digital Economy: The Moligopoly Scenario. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists: Unleashing the Power of Financial Markets to Create Wealth and Spread Opportunity. New York: Crown Business, 2003.

Shapiro, Carl. “Protecting Competition in the American Economy: Merger Control, Tech Titans, Labor Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 3 (2019): 69–93.

Stigler, George J. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2, no. 1 (1971): 3–21.

Concerning state aid, VicePresident Ribera’s mission letter says “you should develop a new State aid framework to accelerate the roll-out of renewable energy, to deploy industrial decarbonisation and to ensure sufficient manufacturing capacity of clean tech. This should build on the experience of the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework and preserve cohesion objectives….. accelerate authorisation of compatible aids and transactions in strategic fields, and to ensure timely clarity for economic operators that cooperate in such sectors, … revise State aid rules to enable housing support measures, notably for energy efficiency and social housing.” Concerning merger guidelines: “modernise competition policy will include a review of the Horizontal Merger Control Guidelines. This should give adequate weight to the European economy’s more acute needs in respect of resilience, efficiency and innovation, the time horizons and investment intensity of competition in certain strategic sectors, and the changed defence and security environment.”

Very interesting, and I largely agree re: antitrust and competition policies in the EU. But the Draghi report also expressed concern about the sheer volume and complexity of other EU regulations (especially tech regulations). I'm curious where you land on those critiques?

So happy I stumbled on to this newsletter! I continue to be impressed by how much insightful content is available on Substack.

Good post! There is also a theoretical question: if a merger does indeed create efficiency gains, e.g., by sharing access to the companies' infrastructure, what prevents these companies to seize upon these gains via contractual arrangements? There's Coase's theory of the firm which tells us that the efficient firm size is reached when internal transaction costs begin to exceed market transaction costs. That's a useful framework, because it points us to where the problem lies: market transaction costs are too high. Said differently, firms wishing to grow to pursue efficiency gains is indicative of the malfunctioning of markets. They cannot exploit the efficiency gains from within the market. Your post offers good diagnosis on what's wrong, and we need more fingers pointing at what's clogging markets and a better understanding as to why this makes us all poorer (whither zero-sum thinking!). I very much enjoyed your posts on the AI act and the costs of failure in that regard because I learnt something about what are the issues. Finally, an afterthought:

One key impediment to efficient contracting (unrelated to regulation) that theorists are quick to point out are asymmetric information in bilateral bargaining. Formally correct. But: Here I would object to this argument: if two firms cannot exploit efficiency gains due to information frictions, how would they know that there are efficiency gains to begin with?