We’ve decided to move the regular Wednesday post to Friday. Additionally, we published a piece last week that we didn’t send to readers on how Europe should respond to the second China shock. Thoughts, disagreements, or ideas are welcome in a comment below or by replying to this email.

We have talked on this blog about the concept of luxury rules: those policies that Europe could only afford thanks to a position of extraordinary privilege.

Here is a striking example. Europe’s leaders like to talk a lot about a ‘wake-up’ on defense (Macron has announced at least one a year since 2022 by my count).1 But the European Investment Bank (EIB), the union's primary lending arm and, in its own words, ‘one of the biggest multilateral financial institutions in the world’, continues to forbid funding for weapons manufacturers.

Only in April 2024 — over two years after the start of the war in Ukraine — did the EIB remove the requirement that dual-use projects (those with both civilian and military uses) must generate over 50% of revenue from civilian applications to receive funding. Core defense activities (weapons) remain subject to exclusion and are banned from funding. Some defense activities can be invested in:

“Military operations have traditionally relied heavily on fossil fuels. As the EU's climate bank, we can finance renewable energy and energy efficiency projects implemented by defence bodies. While enhancing security, these clean energy projects also support the transition to renewable energy sources and the net-zero targets. This includes, among others, projects within: Renewable energy technologies, sustainable military facilities” (EIB)

If this were not tragic, it would be funny. Thanks to these and other exclusion policies, forty percent of European defense companies find access to financing very difficult, compared to just 6.6% of companies overall. Even those companies that have more lenient ESG policies often have policies banning funding for manufacturers of ‘controversial weapons’ that are critical to the fight in Ukraine, including cluster munitions and landmines.

ESG isn’t a unique case. Luxury rules hamstring defense firms across the board. In recent months, the following stories have come out:

“A leading European tank maker, KNDS, was planning to expand a Munich testing range, but had to pause following local complaints, including one from a man who said the work interfered with his meditation, according to a person familiar with the matter. Other residents were concerned that noise from the testing site would affect housing prices.” (WSJ)

and

“In the German city of Troisdorf, Diehl Defence said it has struggled to get permission to expand a factory in the city center to boost production of detonators and other parts for the Iris T missile-defense system, which has formed a crucial part of Ukraine’s air defenses since the war began. Troisdorf’s mayor, Alexander Biber, said the community was in constructive talks with Diehl, but asked whether a city center is better suited for homes or businesses than for factories producing explosives.” (WSJ)

Consider the French Griffon armored vehicle. It is meant to be the workhorse of the army. The truck’s headlights were originally placed high up, but road regulations required them to be lowered to avoid blinding oncoming traffic. This necessitated a complete redesign of the vehicle's front section — only to discover that the headlights were hitting and breaking the axles in their new lower position. What began as a compliance issue spiraled into a significant engineering problem.

Ukraine has shown that drones are the future of warfare. But flying and testing them in Europe is much harder than elsewhere, thanks to stringent civilian air safety regulations. According to a recent French parliament hearing, the Patroller drone is delayed — it has taken 14 years from design to first delivery — due to problems complying with civilian rules governing flights over populated areas.

Then there is the problem of dealing with procurement agencies that are calibrated for peacetime. The Bundestag's budget committee in Germany must approve any defense contract exceeding just €25 million.

An example of what procurement woes can do is Denmark’s sole artillery shell manufacturing plant, in the small village of Elling. A former manufacturing site for munitions, it was closed in 2020 due to a lack of profitability. The Danish state bought it in 2023. They hoped to announce Norwegian-Finnish firm Nammo as a producer a few months later. However, the Danish parliament decided that while Danish firms won’t be competitive, the process should be frozen while they bid for the contract. Construction has been halted for the last year. As the process drags on, the Danish government now estimates that the first shells will roll off production lines no earlier than the end of 2026.

As Admiral Vandier, the NATO Supreme Allied Commander for Transformation, puts it, Europe’s defense woes

"can be summed up as over-compliance… you have to demonstrate that everything is perfect in the [equipment] you're going to deliver in 15 years' time, that not a bolt will be missing."

Where other luxury rules hurt growth and wider economic performance, in defense they are seriously hurting the basic functions of government — keeping its citizens safe.

Just the Danish plant’s problems alone represent at least 10% of Europe’s current shell manufacturing capacity that won’t come online. While somewhat smaller, Russia's 152mm shell costs 25% of NATO's standard 155mm shell. The production time for a 20mm shell casing in France is 6-8 weeks versus less than 2 weeks in Ukraine.

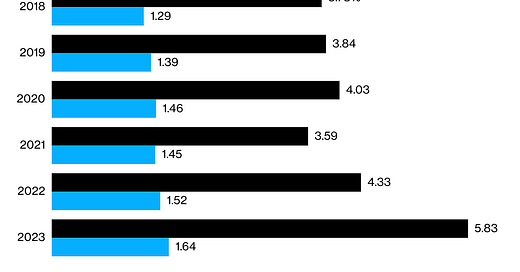

Even as defense budgets rise — €336 billion by this year by current counts in Europe — additional funds have little impact if capacity cannot be expanded, or the marginal euro is largely spent on compliance. And though spending is increasing, European defense firms are still worried about large-capacity investments due to a continued lack of long-term orders.

The luxury rules have an indirect effect as well. It is harder to increase defense spending in a no-growth environment. There is a direct guns-versus-butter trade-off: every dollar spent on defense is a dollar taken away from pensioners or students, neither of whom are keen to give up their share of the pie

Source: Bloomberg

The country with the highest relative defense spending is also the one with the highest average growth: Poland, at €26 billion. As long as much of Western Europe — thanks to excessive regulation — is in a zero-growth environment, increasing defense spending is a political lift.

Not all the news on defense is bad. A common bugbear of European defense thinkers is the fragmentation of production. Draghi mentions that Europe makes 12 types of main battle tanks (MBTs) while America makes just one. But this lack of consolidation in the European defense industry probably led to more redundant capacity than otherwise would have existed. In the United States, the Defense Department regrets forcing its defense firms to consolidate in the 1990s and is suppressing further mergers.

While less ideal than the first-best outcome of a highly efficient industry with high spending, the reality is that consolidation would likely have led to a much greater shutdown of plants and thus an even larger capacity gap.

European politicians — especially after the American election — are desperate to improve European spending, and struggling to find the money. A focus on luxury rules can alleviate those problems. The lowest-hanging fruit is to exempt defense manufacturers from ESG criteria. But serious change would probably only follow if — member state by member state — we saw sustained efforts to free defense manufacturers from the regulatory state that makes it impossible to build quickly or cheaply. In Admiral Vandier’s words:

“Europe can't win the future arms battle with the rules they've imposed on themselves today. If you want to stay in the arms race, change your rules."